They used to say –

perhaps they still do – that the sign

of a misspent youth was the deathly

pallor induced by hours of badly lit

hours in the snooker hall. But there’s

another kind of furtive pleasure, the

kind one enjoys with a mixture of shame

and quiet pride, and it’s a pleasure

licensed by history. It’s called collecting

78s of ballad singing. Sad ballads,

bad salads, I’ve heard all the jokes

and maybe one or two more. When collectors

nestle deep into their wallets and surface

with chequebook and card as payment

for a unique offering of some Moscow

contralto on a 1903 Russian G &

T, I pass by without a blush. For me

it’s Hubert Eisdell and Harold Williams,

Malcolm McEachern and John McCormack,

Richard Crooks and Tudor Davies. And

dozens more, each name a master of the

ballad art, as well as many arts of

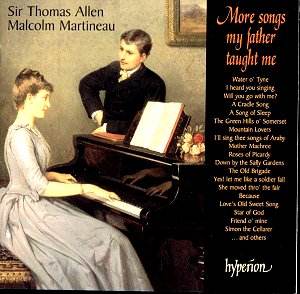

course. Which makes this latest offering

from Allen and Martineau, their second

in this series, an enticing prospect.

These songs simply aren’t sung much

now and it’s a delight to hear them

sung again and so sympathetically.

The composers’ and

lyricists’ names vary in familiarity.

Of the composers there’s Eric Coates,

W.H. Squire and Haydn Wood from the

great days of British string playing

composers, there’s Guy d’Hardelot (née

Helen Guy), ballad songsmith in excelsis

and one of three women composers represented.

There’s a descendant of the Sterndale

Bennett, there’s an aristocrat, a couple

of Herbert Hughes arrangements of Irishry

and some American influence in the form,

inter alia, of Carrie Jacobs-Bond whose

A Perfect Day is one of the canonical

transatlantic contributions to the genre.

In fact the selection is wide and handsome.

So, some highlights. W.H. Squire’s Mountain

Lovers is splendidly done – softened

articulation in the second verse, a

typically strong and forthright ending

as well. I think manly is the mot

juste – typical of Squire at his

most jaw-jutting. Odoardo Barri – crazy

name, crazy guy as a satirical magazine

would doubtless put it – wrote The

Old Brigade to lyrics by Fred Weatherley

who wrote, most famously, for Coates.

It’s an Empire Stirrer all right but

a sensitive one and Allen summons up

spectral military ghosts with gravity

and sensitivity. Allen and Martineau

are splendid in a song I’ve not heard

sung in years, Molloy’s Love’s Old

Sweet Song and they are affecting

in Wilfred Sanderson’s Friend o’

mine. They do all they can for Lord

Henry Somerset’s A Song of Sleep.

Its effect on me was all too literal

I’m afraid though his Lordship redeems

himself with a rather attractive setting

of Christina Rossetti’s poem Echo.

Allen does piety as

well as he does parlour. The pulpit

is in one’s mind’s eye in Coates’s Star

of God. Truth to tell though Coates

evoked hedge and ale better than the

Almighty and this is no buried masterpiece.

Allen’s taste for salt spray and brine

is certainly engaged by the Empire Nauticalia

of Sanderson’s Time To Go: really

stirring stuff. His strong commitment

and darkening baritone serve up a steady

arsenal of winners. Where he misses

the mark it’s a question of degree and

taste, also perhaps ultimately the limitations

of a baritone voice in some quintessentially

tenorial areas. So I’d have liked a

shade more rubato in I Heard You

Singing and whilst there’s a deliciously

aware example of his portamento in The

Green Hills o’ Somerset I’d have

liked even more. He can’t match Tudor

Davies’ declamatory Yes! Let me like

a soldier fall. This is a song much

recorded by inter-War tenors, most prominently

Heddle Nash and Walter Widdop. But when

Davies sang it, by God, you believed

it. Sir Thomas is altogether a more

pacific chap, more cardigan than bloodstained

tunic. D’Hardelot’s Because is

also not quite there. It’s difficult

to put one’s finger on it but it has

something to do with effulgent generosity

and simplicity. Simon the Cellarer

wants more of a wink perhaps – in

avoiding the vulgar or obvious gesture

perhaps Sir Thomas also loses some of

the infectious brio of it all. Try as

he might McCormack stubbornly refused

to vacate my brain in the songs most

associated with him. When he sings of

the fair Irish maid why does Sir Thomas

sing ca-lleen not co-lleen

in The Star of the County Down?

McCormack didn’t. Never mind. Sullivan’s

Orpheus with his Lute, one of

the art-song settings here, is a fine

interpretation of a most superior setting

and the unaccompanied songs that begin

and end the disc are especially touching

and expressive.

The documentation is

really typical Hyperion: extensive,

elegant, and well laid out with texts

and descriptive historical biographies.

The sound is to me rather spread. It

gives a breadth to the voice and Martineau’s

highly impressive accompaniments but

there’s a loss of acoustic focus. If

you have the first volume you’ll need

to add this. To those who have a yen

to hear again Roses of Picardy and

Just a–wearyin’ for you here’s

your perfect opportunity.

Jonathan Woolf

See review

of Volume 1