Supraphon

lacks nothing in courage. Here in their

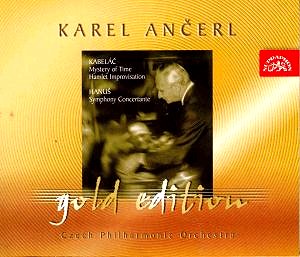

prestigious Ančerl Gold Edition

they choose to place together

three works that previously have been

coupled with more popular pieces. The

received commercial 'logic' is sweetener

and pill. Here there is no sweetener.

Perhaps the Czech company is relying

on what you might call 'collector momentum'.

After all won't collectors want to get

every one of these Gold Editions and

ensure that there is no gap in the numbers?

Of course for explorers

of rare repertoire such series offer

rich pickings. They will have no compunction

about picking up odd discs from the

series to populate their shelves with

recordings of Pauer, Vycpalek, Dobias

and others. Later volumes in this series

include the Kabelac Symphony 5 (SU3701-2),

Burghauser Seven Reliefs and

Dobias Symphony 2 (SU3700-2), Krejci

Symphony 2 and Pauer Bassoon Concerto

(SU3697-2), Vycpalek Cantata of the

Last Things of Man (SU3695-2), Borkovec

Piano Concerto 2 (SU3690-2), Vycpalek

Czech Requiem and Macha Rychlic

Variations (also on the all-Macha

collection from Arco Diva). That's about

six discs out of the 42 volumes in the

Ancerl Gold Edition.

Miloslav Kabelac

began composing in the 1930s and

his formative experiences during the

Nazi occupation and the Soviet regime

included the suppression of his works

with varying degrees of thoroughness.

The Mystery of Time begins

with the merest susurration. The effect

is rather like the shadowed murmurings

of Ives' Unanswered Question.

From about 7.00 (and later at 14.53)

the music takes on a stronger rhythmic

interest sounding Sibelian (though the

notes suggest Janáček)

rising to brazen piercing brass protests.

The chesty and hoarse brass writing

at 10.12 hints at familiarity with Suk's

Asrael. At the climax

at 13.00 and 18.11 the fate motif from

Beethoven 5 is alluded to. This is music

riven with conflict yet fitfully heroic

in character as at the magnificent writing

for high pealing trumpets (19.06). A

more serene tone is struck by the solo

violin in the last few minutes of this

impressive piece. The solo line yet

manages to avoid undue sweetness. There

is something toiling about that solo

voice rather than utterly at peace.

Kabelac made time the

subject of several of his pieces. Such

elitist philosophical obsessions were

anathema to the communist state - another

reason why his music was officially

stigmatised. The work was premiered

by the same forces as here on 23 October

1957.

Ten years later Kabelac

turned to the Hamlet Improvisation.

It was premiered in 1964 by the Prague

Symphony Orchestra conducted by Alois

Klima (whose Supraphon recording of

the Suk War Triptych should be

reissued - does anyone out there have

the LP?). It was written in Shakespeare's

400th anniversary year. Again the solo

voice of the violin can be heard but

the context is more challenging than

that in The Mystery of Time.

The fabric of the piece shows the influence

of Messiaen. At times there is also

an Egdon Heath chill about it.

Moods shift mercurially while questionings

and misgivings challenge the listener.

It is as if we are granted an insight

into Hamlet's disordered mind. This

is a troubled piece with a tendency

to fragmentation rather than long lines

(except in the solo violin) and with

inventive patter from the percussion.

A softer sentiment enters at 7.38 (Ophelia?)

with a soaring insistent theme for the

strings. Once again the work is given

coherence and logical momentum by the

return of the solo violin (underpinned

by the bassoon) at the close.

Both Kabelac works

avoid serialism and the dodecaphonic

method but, especially in the Hamlet

work, are happy to grasp dissonance

as part of the expressive armoury. Kabelac

is not afraid to use repetition and

subtle transformation of material to

bring us closer to his language.

Jan Hanus won

the Dvořák

Prize in 1954 for his Symphony

Concertante. It was written

during the long ascendancy of the socialist

cantata exhorting conformity and exulting

in the praise of Stalin and his fledglings.

However what we find in the Hanus work

is a piece with decidedly

serene inclinations - quite the opposite

of Kabelac. It sounds positively Gallic

with shades of the Poulenc Organ Concerto

yet not gargantuan Gothic. The confident

string writing blends in the style of

Dvořák from the Seventh and Eighth

symphonies. The harp plays a

prominent role throughout acting as

an assured orator at every step. It

was a brave choice to put the harp up

against the organ. Hanus's writing is

not desperately original but it is extremely

effective within the bounds of Tchaikovsky

and Ravel. The fugal finale is similar

to the final section of Britten's Young

Person's Guide. Although things

begin to become structurally ramshackle

toward the end it would pair nicely

with William Alwyn's Lyra Angelica

and I am sure would have appealed

to Alwyn.

I wonder if he ever heard it. The Hanus

is dedicated to Ančerl. Its premiere

took place in Brno in 1956 conducted

by Otakar Trhlík. Ančerl made this

recording in 1957.

The notes are good

although I would have liked more biographical

background on the composers. Recording

quality is at its least plush, though

still adequate, in the Hanus.

Rob Barnett