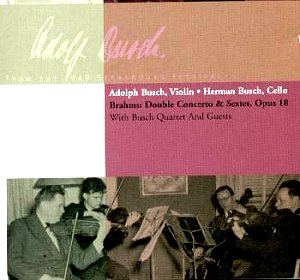

It was fortunate that the Strasbourg Festival of 1949

attracted the attention of some recording apparatus. These performances

were recorded on lacquer discs and the technical reconstruction has

been undertaken by Maggi Payne. The Double Concerto emerges dimly but

in still perfectly listenable sound but the Sextet is very much more

problematical; I doubt if anyone could extract better sound than Payne

has managed and we should be grateful that these performances have survived

at all, filling gaps in Busch’s discography as they do.

Relatively plentiful now, there was a time when the

only recording one could buy of the Double Concerto was the Thibaud-Casals-Cortot

set recorded in Barcelona. Others appeared in the two decades that followed

– Heifetz-Feuermann-Ormandy (incandescent), Kulenkampff–Mainardi-Schuricht,

and Oistrakh-Sadlo-Ancerl but Adolf Busch, noted Brahmsian though he

was, never recorded it commercially. Which was not perhaps surprising

given the existence of the Heifetz-Feuermann. That deficiency has been

righted here in a performance that takes a far more measured and considered

view of the score than their Russian contemporaries, though one slightly

quicker than, say, the familiar Oistrakh-Fournier-Galliera recording.

The relative dimness of the aural perspective makes

for occasional imprecision in the orchestral sound, added to which Hermann

Busch, fine chamber player though he was, was not a soloist and for

all the phrasal sensitivity and interplay with his brother the gruffness

of his playing and the frequent lack of centring of the note can and

does prove problematical. I admired the elucidatory and revelatory phrasing

by both brothers at 9.30 – great nobility and elevation of phrasing

with the seamless limpidity of their exchanges - and the absence (expected

of course) of gladiatorial theatrics, such as does sometimes limit the

Heifetz-Feuermann recording. The principal clarinet of the French National

Radio Orchestra is also in fine form and proves a player of distinction.

In the slow movement there is great raptness of phrasing though arguably

it is too predictably effected through increases in vibrato usage and

bow pressure. There are however pleasures in the unusual angularity

of the cello line and the ways in which Hermann Busch cleverly varies

phrases and employs his still gruff but now keening lower strings. They

keep things moving but still have plenty of time for lyrical introspection

(they are slightly quicker than Oistrakh-Fournier but much slower than

the galvanic Heifetz-Feuermann (8.03 against the Russians’ 6.47). There

is real lightness in the finale – this is the best played and interpreted

of the three movements – with some almost gnomic exchanges between the

string players and much scurrying, flighted passagework. Kletzki abets

this with a really felicitous care and energy.

The Sextet, as I indicated, is in rather poor sound,

muffled and very much to be taken on trust, the first movement especially.

We can still make out much though, with Albert Bertschmann (viola) and

August Wenzinger (cello) joining the Busch Quartet. Wenzinger will be

better remembered for his popular viol consort. There is flexibility

in the opening movement and a dignified and affectionate cohesion to

the famous Andante that lifts it beyond the static and sepulchral performances

one sometimes hears. The Scherzo is fantastically fleet, a headlong

dash phrased with insinuating and life enhancing lightness. The Rondo

finale suffers increasing aural problems – break ups and distortion

but is taken at a gracious and elegantly flowing tempo. There’s an encore

– all announced by the way – of the Mendelssohn Capriccio, which is

full of winsome clarity and soaring verve.

Jonathan Woolf