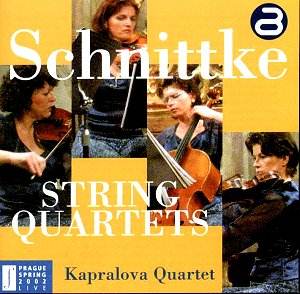

The

first thing to note is that these are immensely accomplished performances

made live at the 2002 Prague Spring by the all-female Kapralova

Quartet – who have recorded their namesake’s highly impressive

quartet recently. The second is the complex difficulty of much

of the music. The greatest difficulty lies in the First and for

me least rewarding of these three recorded quartets. The First

dates from 1966 and is a tough atonal work in three movements,

Sonata, Canon and Cadenza. Formally this may seem explicit but

the greater truth underlying the quartet is that it enacts a kind

of catastrophic implosion in which a musical disintegration takes

place before our ears. When it returns the twelve note row re-establishes

a degree of tangible order but what has gone before is frequently

harrowing. There’s plenty of pensive material, abrasive pizzicati

and coruscating drama. Though the Canon utilises a set of variations

one’s ear is drawn to the Cadenza, violently charged and volatile

that leads to the return of the tone row; never had I longed for

one more. This is tough, astringent and demanding music and demands

completely concentrated listening.

The

Third Quartet was written for the legendary Beethoven Quartet

in 1983. It’s in Schnittke’s polystylistic form and establishes

and embraces a kind of historical continuum from Lassus to Shostakovich.

Schnittke quotes from Lassus as he does briefly from Gesualdo

in the opening Andante. Even here, where the material is more

musing and introspective Schnittke is prepared to unleash some

vicious sounding trilling. The Agitato second movement is eager

and vibrant with attractive unison passages alternating with prayerful

Renaissance glints, cumulatively impressive and compellingly moving

in the way he was often moving, as, for example the Viola Concerto.

The finale is by contrast brittle, tense occasionally relaxing,

shadowing Shostakovich. The Fourth Quartet was written in 1986

after his catastrophic stroke and there is a new soundworld here,

one of stillness, refraction and absorption. The sense of concentration

is overwhelming in terms both of material but also of sonority.

He still exploits registral extremes but these demands are not

arbitrary and are securely locked into the emotional fabric and

trajectory of the piece. In the second of the five movements,

an Allegro, there is real bristle and drive, real colour and drama

whereas the succeeding lento is exceptionally complex; time seems

to stand still. The Quartet is based on a slow-fast-slow-fast-slow

pattern and the fast movements can be almost suffocatingly febrile,

fraught and calamitous. It would be easy to read the work as an

autobiography but it makes "sense" in strictly musical

terms as a intensely coiled drama both violent and meditative.

The disc ends with Schnittke’s moving elegy to one of his models,

Stravinsky.

Jonathan

Woolf

The

Arcodiva catalogue is now offered by MusicWeb

![]() for

details

for

details