The decline in the classical music industry over

the past few years has been marked by the termination of contracts

and the aborting of recording projects with many staff being made

redundant. What cannot be done away with is the recorded archive.

However, if its retail value is to be realized, then market awareness

should be present and functioning in the staff that remain. If

the inadequate presentation of the sixteen operas in this latest

release from the Sony archive is any indication, there must be

real doubt about whether there is anybody left in that company

with a vestige of marketing expertise. The leaflet introduction,

in German and English, devotes a mere seven lines to the plot

and without any track indications either. There follows a track

listing with the opening phrases in the normal way, but without

any indication as to which character or characters are singing.

It is possible to get away with this with the likes of ‘Madama

Butterfly’ (reviewed elsewhere on this site), which is so well

known, but not so for lesser-known works such as this Gluck opera,

or the majority of these issues, which don’t even give the vocal

registers of the singers. I write the foregoing as much in frustration

as anger that such a presentation will limit the commercial appeal

of these discs which some accountant will then decide to have

deleted from the catalogue, consigned to slumber in the archives.

Whilst few of these issues might be first choice, they are all

worthy to be present in the catalogue.

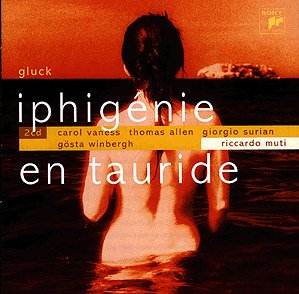

This 1992 recording, with the full ‘La Scala’

forces, came into direct competition with John Eliot Gardiner’s

1986 Philips recording and without displacing it from critical

affection. In attempting to master the fiendish acoustics of ‘La

Scala’ the engineers set the solo voices very close with the orchestra

and chorus set further back in the sound perspective. This has

the disadvantage of accentuating the vibrato in Carol Vaness’s

voice. Hers is a big toned dramatic interpretation, perhaps lacking

something of the ethereal quality that the part needs and gets

on later more scholarly interpretations. However, whilst I do

like her fuller tone, and her ‘Ô malheureuse’ (CD1 tr. 30)

is formidable, by scene 3 of the last act (CD2 trs. 21-23) I found

her vibrato more intrusive and the forward recording of the voices

distinctly tiring. As Pylade, Gösta Windbergh is open-toned,

elegant and sensitive in his phrasing (CD 1 tr. 2). I could sense

from this recording the Wagner roles to come before his premature

death. Windbergh’s sensitivity is to be preferred to some of the

big voiced Italian tenors who have recorded the role.

Thomas Allen repeats the characterful Orestes

he recorded for Gardiner. His burnished tone and vocal manners

make him ideal in this repertoire. The Thoas of Giorgio Surian

is woolly of tone but the part is small. The minor parts are adequately

sung by the theatre comprimarios. Any ‘La Scala’ performance will

revolve around the work of the chorus and the conductor’s interpretation.

In Gluck’s reform operas the chorus is a vital component and here

the Scala forces are vibrant and well articulated, especially

welcome when they are set back in the aural perspective. Muti’s

interpretation is hard driven and furious at times, but that is

valid and better than the nondescript placidity that is the downside

of some later, supposedly more scholarly, interpretations.

This recording deserves its place in the catalogue.

Pity about the presentation though.

Robert J Farr