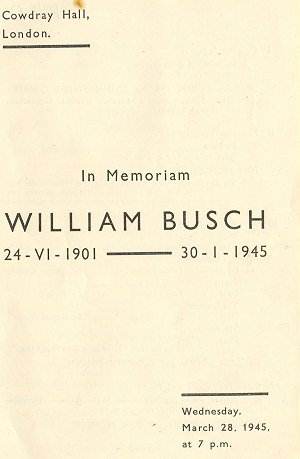

WILLIAM BUSCH by Sinclair Logan

William was born June 25th 1901 and died at Woolacombe, Devonshire

in January 1945. His parents, who were originally German, became

naturalised British subjects some time before the first world

war. Part of his early childhood was spent in South Africa, but

he received most of his education at various schools in England

and the USA. The variety of these early influences and environments

no doubt played its part in the making of a man who belonged in

no way to any ordinary type. Even as a boy he must have been completely

bilingual, for he spoke in German with many of his relatives and

English with most of his friends and teachers.

Music interested him when he was a child and he received piano

lessons at an early age. But he was in no sense an infant or child

prodigy and it was not until he was about 16 that his remarkable

talent was revealed and he decided to make music his career. He

was then in America and his first serious musical studies were

under France Woodmansee. He returned to London after the first

world war. In 1921 we went to Germany where he studied piano with

Leonid Kreutzer and harmony under Hugo Leichtentritt. In May 1924

he returned once more to London and it was there that the major

part of his musical training took place, under Miss Mabel Lander

for piano, with Alan Bush, Ireland and Van Dieren for composition.

He gave his first London recital in October 1929 at the Grotrian

Hall and his first broadcast in December of the same

year. He also appeared in Holland, Germany and the USA.

It was in composition however, that his chief talent lay. The

first evidence of this was the Gigue for piano, composed in 1923

which, if it did not show the marked originality of his mature

style, did at least reveal in a most effective piece, a composer

who was in full command of his technique. This was followed in

1927 by two pieces for wind instruments, which were first performed

in that same year. In 1928 he produced the first of his larger

works, Theme, Variations and Fugue in F Minor for piano. Here

we can see his mature style, his originality and vigorous contrapuntal

thinking which is entirely fresh, unconventional and convincing.

Then follows another interval of five years during which Busch

must have been too much occupied with concert work to allow him

either the time or the undisturbed state of mind which he needed

for composition. In 1933 came the Allegretto Quasi Pastorale,

a pianoforte piece and his first three songs. From 1935 composition

came more to take its rightful place in his life and concert appearances

became rarer. In this year appeared an Intermezzo for piano and

two more songs, none of these were published, though one of the

songs, a setting of the sixteenth-century lyric "Weep You No More"

ranks among his finest inspirations

1937 was an important year, for it produced a fine and original

setting for voice and string quartet of the "Ode to Autumn" by

Keats which, though it has received several performances, is not

yet published. In this year he also composed one more song and

began work on the Piano Concerto in F Minor which was completed

in 1939.

1939-40 came the Piano Quartet, dedicated to The London Belgian

Piano Quartet, who have given frequent performances of it with

great success and in January 1939 his Piano Concerto received

its first performance in a broadcast by the BBC Orchestra with

Clarence Raybould conducting and the composer as soloist. In the

same year he composed a Passacaglia for violin and viola. Shortly

before the outbreak of the second world war he was invited to

Paris to give performances of some of his compositions.

The war was to him a deeply personal tragedy, a fact which became

sharply discernible in some of his later works. During the few

years of his life which remained the profound distress which was

wrought in his highly sensitive nature often caused periods of

ill-health and the fact that he had relations and intimate friends

on both sides of the conflict did not ease the pain. This also

had an effect on his composition, which was brought to a standstill.

In 1940, after a short illness, he wrote in his diary "more

at ease now that composition is going more smooth/y. That is my

life!"

He spent the rest of his life at Woolacombe, Devonshire and served

in the Auxiliary Fire Service. The following works appeared during

his last five years:

1940-41 the Cello Concerto, which was, in his own words,

"inspired by and dedicated to Florence Hooton" who gave the work

its first performance at a "Prom" with Sir Adrian Boult conducting.

1942 The 'Nicholas Variations' inspired by his three-year-old

son, one of the most original and daring of his works.

1943 Three pieces for violin and piano, a suite for cello

and piano (of which the Prelude is one of his noblest conceptions)

and seven songs.

1944 A short but very remarkable song-cycle "There have

been happy days" comprising settings of five poems by Wilfred

Gibson. Also, four more songs, a piece for cello and piano entitled

" A Memory" (Elegie) based on the concluding song of the cycle.

At the time of his death Busch was at work on a violin concerto

but all that exists of this is a sketch of the first movement.

In January 1945 a daughter, Julia, was born. While visiting his

wife in a nursing home at Ilfracombe, all transport ceased owing

to unusually heavy falls of snow. It was essential he should return

to his little boy that night so Busch walked back to Woolacombe

along the now almost impassable cliff path which the snow had

made dangerous. On reaching home he was excessively exhausted

and very soon serious internal haemorrhage set in. No doctor could

be obtained in time and thus he died.

Busch' s nature was both sensitive and responsive and he had

a great capacity for strong and lasting friendship. He rated humanitarian,

ethical and spiritual values so highly that one would be tempted

to describe him as deeply religious, were it not that the term

usually implied an orthodox type which he in no way resembled.

Part of his nature was in close touch with his fellowmen, understanding

their weakness with a kindly sympathy, but another side of his

character was intensely introspective - remote and very much alone.

For one who shrank in acute distress from hurting anyone, his

fearlessness in saying what he felt should be said, on occasions

when others would seek refuge in silence, was a remarkable attribute.

He was unsparingly self-critical in all matters and this together

with the distraction of concert work may account for the reason

why his output was comparatively small. His music is invariably

the expression of his own nature and this is manifest in his work.

Busch was a composer whose work reveals a steady growth in all

its aspects, so much so that it is interesting to imagine what

he might have achieved if he had lived longer. By the time he

had found his maturity in the Theme, Variation and Fugue for pianoforte

and in the early songs, his music bore characteristic features

which were unmistakably his own. These never became mere mannerisms,

but they constantly recur in all his work. There is, for instance,

his fondness for the falling augmented fifth from the leading

note in a minor key; his use of isolated fragments of melody,

in quiet octaves, involving the use or suggested of the augmented

second; and, in especially in the later songs, his uncompromising

handling of major sevenths and minor seconds. The earlier works,

even of his mature period tend to be a little profuse in material-

excluding the Theme, Variations and Fugue for piano, which is

a model of concentrated, closely woven conciseness. As he developed,

however, his style became more economical and his writing, though

often highly complex, far less j complicated. His music is essentially

contrapuntal in character and he rarely uses a purely harmonic

medium. The few instances of this occur only in the songs and

then only when some element in the poem seems to him to demand

it. His most strikingly effective use of purely harmonic writing

occur in the powerfully arresting little song "The Snowdrop in

the Wind" of 1943 and the Song-Cycle of the following year. It

is rarely, if ever, possible to judge even the best of Busch'

s melodies independently of their background in the music or their

position in the work as a whole: it is the total effect of all

the elements in the texture which matters.

His large scale compositions are finely wrought works, thoughtful

in conception and impressive in performance. The Theme. Variations

and Fugue have already been described and the 'Nicholas Variations'

for piano of fourteen years later have an uncompromising boldness

and a startling originality in their presentation, the child soul

urgently clamouring to grow. The two concertos are symphonic works

of a very high order, in which form and content are finely balanced:

they are also well written for soloist and orchestra alike. The

Piano Quartet is a fine, virile work, brimming over with vitality

and of all the larger works is probably the one which makes the

most immediate appeal to audiences.

Lastly, the Song-Cycle "There have been Happy Days" though it

consists of only five short songs and occupies no more than ten

minutes in performance, should rank with the large-scale works,

because of its masterly design and its significant character.

This is perhaps his best achievement, the Work in which all his

finest qualities seem to reach a climax of concentration. None

of the early profusion here, only a ruthless economy of material.

The work is complex, yet stark in its clear-cut conciseness. A

group of themes (and one of these in particular) dominates the

cycle throughout and these are handled with intensely dramatic

effect. This song-cycle is the complete expression of Busch's

life. It is in fact in his songs that Busch was most original,

always excepting the 'Nicholas Variations', and it is not yet

generally realised that he actually wrote a new page in the history

of song. With Busch, more than any other composer, except Van

Dieren, the song must be regarded as a complete fusing of all

its constituent elements, but Busch, by a flash of intuition and

in the simplest possible way, often achieves a result similar

to that which Van Dieren arrives by far more complicated and elaborate

methods. Busch is at his best in his more serious songs, and at

his least effective in his settings of Blake's "Laughing Song"

and Herrick's "Fairies". Many of Busch's songs were written for

and dedicated to his friend Sinclair Logan

Among Busch' s smaller instrumental compositions, players will

search in vain for the "Morceaux" or the effective trifle, but

they may seek and find music of a sincerity and a poetic beauty

of which they will never tire.

Sinclair Logan May 30th 1950