Iíd actually never seen a photograph of Wirén

before receiving this for review. Here was a man whose most celebrated

critical comment (and albatross around his neck) was his artistic

credo beginning, with Biblical surety, I believe in Bach, Mozart,

Nielsen and absolute musicÖIt is indeed remarkable against

this background how his physiognomy resembles Nielsenís. If Wirén

saw himself as Son to Nielsenís Father the physical resemblance

is uncanny from the up and over quiff, tight lips, guarded eyes

and prominent ears. Leaving aside such matters for a moment, this

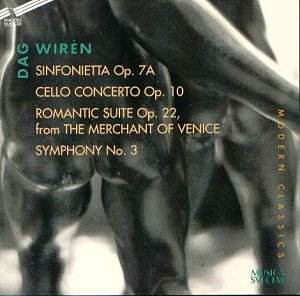

Phono Suecia disc traces Wirénís rather earlier self, from

the Opp. 7 and 10 to the Third Symphony of 1943-44 and the Op.

22 Romantic Suite derived from The Merchant of Venice Ė

by which point we are approaching the canonical Wirén.

The Sinfonietta was a leftover from an unsuccessful

attempt at a youthful Symphony begun in Paris. It starts with

genuinely motoric strength and has a second subject that is flooded

with a beautifully wistful song that soon leads on to a brassily

ceremonial section. The second movement is affectionate, full

of plangency and Nordic mist, with a solo trumpet coursing evocatively

and alone above the arching string line. Thereís incipient grandeur

here and a power that Wirén cleverly never quite unleashes.

The vista is embryonic Wirén and most impressive. Thereís

a martial finale with plenty of perkiness as well as some pawky

winds some sounding distinctly Sibelian. Off-beat pizzicati appear

whilst triumphant percussion are cut short by the conclusion authoritatively

carried off by the strings.

The Cello Concerto was composed in 1936 for Wirénís

great friend Gustav Gröndahl, who gave the premiere in Stockholm

three years later. It predates the famous Serenade by a year and

is a short, sixteen-minute work cast in three movements. The first

movement is imbued with a subtle march character, the solo cellist

exploring his line with tenacious grit, the brass becoming more

and more insistent. The movement becomes increasingly less discursively

pliant as it develops. There are some moments of reverie and reprieve

for the soloist. I was immediately struck by the slow central

movement which starts with real nobility but is almost immediately

cut abruptly short by a dramatic attacca subito episode. This

is actually the direction of the second movement of the Sinfonietta

but it applies equally Ė actually rather more accurately Ė to

this work. The end of the movement is somewhat modal and also

curiously and deftly antique in utterance, as if Wirén

were evoking some fictive past. The Allegro conclusion is chirpy,

melodic, full of expressive little orchestral moments and harmonic

individuality. I suppose critics would point to the slow movement

as being evidence of Wirénís relative brusqueness of melodic

inspiration. I prefer to see it as a curious and distinctive approach

to the concerto and to the function of the slow movement in particular.

The Romantic Suite from The Merchant of Venice

dates from 1943 (and very lightly revised in 1961). He wrote quite

a considerable amount of theatre music and these five, short movements

attest to his idiomatic understanding of the medium. The opening

is full of melancholy and its successors are rumbustious and jolly

with overtones of Stravinsky and Prokofiev. The Third Symphony

is the final and most impressive work here. It was written during

the War, between 1943 and 1944 though constantly interrupted by

Wirénís military service. Again this is in three conventional-appearing

movements, fast-slow-fast. It is a compact, incisive work, free

of extraneous and superficial matter. The first movement is thrustful,

with deep brass driving forward with a definably baleful menace.

The Adagio has a strong, sometimes yielding profile, but the lines

are long. Critics who complain Wirén is short winded should

listen. The harmonies are distinctive; the structure is tight,

the atmosphere sometimes aloof though not cold. The finale, the

longest of the three movements has a certain ambiguity at its

heart. The orchestration is splendid, and thereís real elasticity

in the writing, encompassing quicksilver changes of mood and emotive

states. The reflective passage at 8.30 is one of those "Wirén

moments," and the almost immediately eruptive Sibelian brass

(I think of the Fifth Symphony here) and their effulgent, burnished

confidence take the Symphony to the point of anticipatory triumph,

a belief in the future. The cymbal clash that leads to increased

elevated power ends the work in triumph.

Performances are strongly committed. Lidström

is a soloist who marries technique with expressive insight and

the Sami Sinfonietta and Stefan Solyom are accomplished exponents.

No complaints about the sound quality or about the precision of

the notes.

Jonathan Woolf

![]() Mats Lidström (cello)

Mats Lidström (cello)

![]() PHONO SUECIA PSCD 716

[71.53]

PHONO SUECIA PSCD 716

[71.53]