|

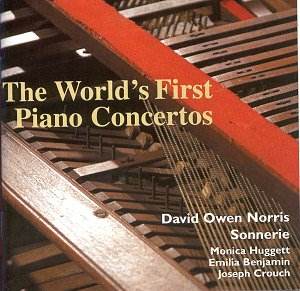

This CD champions the

square piano, that instrument of the 1770s

which introduced the keyboard to a wide

amateur audience. The problem with the

Square piano is that the dampers were

raised by two hand levers (one each for

treble and bass) rather than a sustaining

pedal, and thus it was characterised by

what pianist David Owen Norris describes

as a "halo of resonance". This

characteristic has been seen as a fatal

disadvantage in assessing the square piano

as having a serious role in playing the

repertoire of the day.

In this programme of

Piano Concertos played on a restored Zumpe

& Buntebart square piano of 1769,

David Owen Norris triumphantly demonstrates

how the birth of the piano concerto in

the London of the 1770s can be experienced

in the music of J.C. Bach - the "London

Bach", Carl Friedrich Abel; James

Hook (the bard of Vauxhall Gardens - recorder

players will probably have encountered

his music among their first "proper"

sonatas) and Philip Hayes, Professor of

Music at Oxford. The latter, Norris reminds

us, was renowned as the fattest man in

England. More importantly, Norris argues

that Hayes’ Concerto in A major of 1769

can be regarded as the world’s first.

One can well see how spare the textures

of the concerto would sound if played

on a modern piano, or on a harpsichord,

yet here they take on a persuasive and

idiomatic character all their own.

The ensemble supporting

David Owen Norris at the square piano,

consists of two violins and cello. They

are recorded in the Music Room at Hatchlands,

the home of the Cobbe Collection at the

National Trust property at Hatchlands

Park, Surrey. The microphone catches the

ensemble persuasively. The performances

are poised and crisp, Norris scaling his

pianism perfectly to the instrument. If

one responds most immediately to the J.C.

Bach Concertos, this is an enjoyable exploration

of the music that would have been on offer

to the active music lover in the London

of the 1770s.

In his fascinating and

erudite booklet notes Norris draws our

attention to J.C. Bach’s Sonata in D,

which in the hands of the young Mozart

became the latter’s Concerto in D K107.

For this Norris plays another square piano,

built by Zumpe in 1777 or 1778. This still

has the original buckskin hammer-covers,

and as Norris notes, this means it cannot

be played very frequently. Signed on the

soundboard by J.C. Bach, it is exciting

to realise that it is very probable that

both Bach and Mozart played it. In the

face of this we may applaud Norris waxing

almost lyrical in the conclusion to his

notes, writing: "It seems certain

that this autographed piano, found near

St Germain, was taken there by Bach on

his 1778 visit and ... in this case Mozart

would have certainly played it. ... For

his own concerts in 1772 Mozart arranged

three of Bach’s Op.5 Piano Sonatas as

Concertos, with accompaniment for string

trio. ... what better than to play one

of these works of homage from the young

composer to his mentor on the very keys

both composers touched together in that

long-ago summer of ’78?" Makes you

want to stand up and cheer, doesn’t it?

The sound and the playing

live up to ones expectations. Try the

catchy first movements of the Abel or

the Hook concertos to see if it is for

you. For me this is practical musicology

at its best, at once enjoyable and enlightening.

It is also one of the longest-playing

CDs to have come my way

Lewis Foreman

|

![]() for details

for details