We’ve all seen the famous portrait of Schumann made late

in his life after Clara had got him dressed up and starched and

on his good behaviour for the photographer. But I have seen two

drawings of Schumann as a college student. If I at that age had

ever met him at that age I’d have run for my life. The wild fire

in those eyes promised adventures, vices and risks beyond anything

I could ever survive (and I’m pretty crazy myself as you’d quickly

find out if you knew me). We imagine Frederick Wieck had heard some

pretty wild stories and was scared to death when his daughter actually

wanted to marry this monster. He shouldn’t have worried; Clara was

Isis incarnate and so much of a mother that eight children, a crazy

husband, and a crazy surrogate lover (Brahms) could scarcely soak

up the greater part of all her motherliness.

Katsaris plays the complete manuscripts of the

Etudes including, apparently, some incomplete sketches,

and times out at 18:13, nearly twice as long as Vorraber. I was

driving somewhere when I first heard the Katsaris recording on

my car radio; at once I forgot all about where I was going and

instead drove directly to the record shop and bought the CD, which

remains my absolute favourite recording of any piece by Schumann.

While listening at home I keep glancing into the shadowy corners

of the room to make sure there are no ghosts. The Vorraber performance

is admirable but does not threaten to raise any shadows. Vorraber

plays only the latest of the three manuscripts, timing at 10.46

minutes. He evidently considers some of this music, which Katsaris

sees as complete and worthy of performance, to be ‘unfinished,’

a curious decision to make for a ‘complete’ set, but then Demus

and Ashkenazy omit these pieces from their sets entirely.

The Albumblätter are twenty miscellaneous

little pieces, sounding much like other miscellaneous little Schumann

pieces; the playing is precise, dramatic, and idiomatic, but at

times I found it hard to keep my attention on them, even though

number 17, ‘Elfe,’ is a marvel of pianistic skill. Some may prefer

these rather cool performances, but I look for those uniquely

Schumann passions in this music and I don’t hear them here.

The Sonata Op. 22 is more interesting and here

better performed than the Op. 124, especially with the original

finale added as an appendix. But while the alternate movement

is interesting, it is also somewhat wayward, and you will probably

prefer the final published version of the sonata. But if what

we hear from Vorraber here in the first movement is truly so

rasch wie möglich, (‘as headstrong as possible’) I’m

crazier than Schumann was. Vorraber plays brilliantly, but rather

too tastefully, without abandon. His cool brilliance is much more

successful in both versions of the fourth movement. Demus plays

with brilliant ferocity. Kempff plays with a just sense of ‘rasch,’

with a lurching, stumbling forward movement, musically dramatic,

but without undue speed. ‘So rasch wie möglich’ is not, as

some dictionaries would have it, ‘so schnell wie möglich’

(as fast as possible).

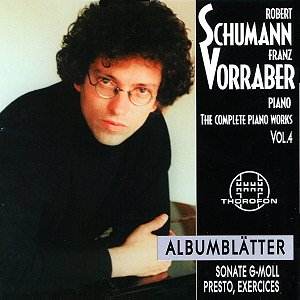

Herr Vorraber is all smiles on some of the covers

in this series, but on volume 4 he looks solemnly out at us, putting

much effort into looking as though hurtling himself into the Rhine

is one of the things he has thought seriously about doing recently.

I would not want to suggest that Herr Vorraber has no depravity

in his soul; that would be a terrible insult these days, so I’m

sure he is fully capable of being just as depraved as he sets

his mind to be. But I doubt if he has ever travelled to that place

where the birds are dead and heard the thing that yet chirpeth

like a bird, whereas Schumann probably visited there most days

of his life.

My favourite modern Schumann piano recording

is the ADD Kreisleriana by Vladimir Ashkenazy, but until

January 2003 no one had seemed to agree with me as this performance

was not until then made available on CD. While I revere Jörg

Demus as one of the great pianists of the 20th Century, his Schumann

set is a little disappointing, mostly because of indifferent recording

and a piano in need of new strings and hammers. Schumann’s music

most clearly defined the goal for the developers of the modern

concert grand piano, and using an ‘historic’ instrument would

in this case be a mistake.

Schumann had the worst in-law problems imaginable

that started years before the marriage. His fiancée’s father

would scream and spit in Schumann’s face whenever they met by

chance on the street. The elder Wieck repeated loudly a rumour

he had heard, that Schumann was syphilitic. This diagnosis was

also borne out by the attending physician at his death, but has

recently been disputed. It used to be believed that Beethoven

had died of syphilis, but now we know that wasn’t true. Recent

discussions* have suggested that Schumann suffered from three

distinct illnesses: His family suffered from an inherited tendency

to mental instability and early death, and he must have known

this from an early age, which would hardly have improved his morale.

His father died at 52, his three brothers at the ages of 28, 43

and 48, and his sister committed suicide at 19. Robert’s dying

at 46 could be seen as just what he might have expected. Also,

Schumann displayed all the symptoms of bipolar disease, formerly

known as manic-depressive disorder. Finally, Herr Wieck was likely

correct — Schumann did have syphilis. The mercury treatments he

endured prevented him from infecting his wife or children, but

no doubt exacerbated his mental instabilities, and could not save

him from the final onslaught of the tertiary form of the disease.

It’s a pity Schumann was not successful at drowning himself after

his famous leap into the Rhine; for the next two years he suffered

terribly from hallucinations and delusions before death finally

and mercifully released him. That a man who suffered so much was

able to write anything at all is some kind of miracle, and the

fact of its amazing quality makes it even more so. Music must

have been for Schumann a kind of anchor that kept him at least

within hailing distance of sanity.

The only happy note one can find in this story

is that after his failure to stop the wedding, Herr Wieck wrote

Schumann a touching letter of apology and subsequently the whole

family would gather together on holidays and maintain at least

formal conviviality.

Vorraber’s piano is excellent and he attains

better sound than Demus. I feel that both Vorraber and Demus deserve

high marks for splendid attempts but we have yet to hear a fully

satisfactory complete Schumann set. In the meantime it is easy

to console ourselves with the less than complete but extensive

series by Ashkenazy, which also receives excellent recording,

both ADD and DDD.

*Robert Schumann, The Man & His Music,

edited by Alan Walker, 1972.

Paul Shoemaker

![]() Franz Vorraber, piano

Franz Vorraber, piano ![]() THOROPHON CTH 2516 [72.26]

THOROPHON CTH 2516 [72.26]