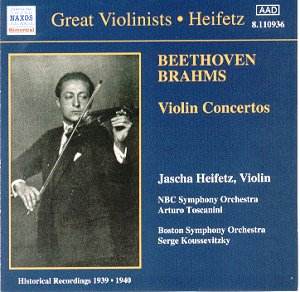

These are really splendid transfers by Mark Obert-Thorn

of two famous recordings of the two greatest violin concertos in the

repertoire. It seems superfluous to add that the confluence of Heifetz,

Koussevitzky and Toscanini makes for riveting listening. The Victors

of the Beethoven preserved a performance recorded in Studio 8H and they

bore all the obvious auditory features of that venue of airless deadening

Ė limiting factors mitigated in this transfer to a successful degree.

This performance and that of the Brahms have occasioned considerable

debate Ė pro and contra Ė over the last sixty years, which must indicate

something of their powerful individuality at least. I can imagine strong

and convincing arguments on both sides and my own view is that the Brahms,

though strongly personalised, is the more convincing and sensitive performance.

Toscaniniís accompaniment in the Beethoven is inclined

to abruptness, though he undeniably prepares for the soloistís broken

octaves entry far better than does Bruno Walter for Szigeti in their

performance (also preserved on Naxos 8.110946). Heifetzís seemingly

effortless virtuosity (itís a prerequisite of virtuosity that it "seems"

effortless) is astounding, Toscanini full of complimentary orchestral

clarity and architectural cogency. Heifetz plays his own adaptation

of Auerís cadenza in the first movement. What remains troubling is an

air of fluent certainty. This is not a criticism of Heifetzís peerless

playing in a technical sense Ė rather a sense of not what is present

but what is absent from the performance and what is absent becomes more

distressingly clear in the Larghetto. This is a superficial and rather

decorative, gestural reading laced by Heifetzís luscious tonal resources.

But no more than that. The finale is robust, vigorous Ė though surely

a few of the scratches one can hear were eliminatable? Ė and Studio

8H exaggerates the aggressive precision of the playing. Some of the

lower frequencies are overloaded and an over-congested perspective emerges.

I canít say Toscaniniís conducting here impressed me with welcoming

affection.

Koussevitzky directs a strong, fluid performance of

the Brahms, a work that suited Heifetzís emotive urgency rather better

than the more complex intricacies of the Olympian Beethoven. He engages

in any number of finger position changes that give muscular impetus

and life to the solo line, flecking the first movement in particular

with a spectacular array of ear titillating moments. Some of these are,

admittedly, very spicy indeed and some may well feel him insufficiently

weighty, sacrificing depth for sumptuous incident, rather in the manner

of his fellow Auer-pupil, Toscha Seidel. But Heifetz never loses the

architectural sureties here and is technically on something of a different

plane to his contemporary competitors. Note that he plays the Auer-Heifetz

cadenza in the first movement. I admired the second and third movements.

The Boston oboist is impressive and Heifetz sensitive in the second

movement. In the finale Heifetzís forward motion cannot be, except superficially,

equated with glacial indifference. As with his later recording of the

work with Fritz Reiner, Heifetzís Brahms is a muscular, powerful and

convincing one on its own terms.

Whatever oneís judgement these are durable examples

of superior musicianship Ė though arguably not ones tinged with metaphysical

depths Ė and to have them in such fine transfers, at such superbudget

price, is reward in itself.

Jonathan Woolf