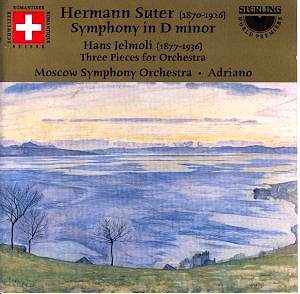

Bo Hyttner's Sterling label opens up another vein in

symphonic music: the music of Hermann Suter one of the Swiss traditionalists.

From the same genre Sterling have already recorded the eight symphonies

of Hans Huber written between 1881 and 1921. Awaiting appraisal are

the two symphonies by Robert Hermann (1895, 1906), Fritz Brun's ten

(1901-1953), Robert Oboussier's 1936 symphony and Walther Geiser's symphony

of 1953.

The four movement symphony was written on the cusp

of the Great War and was premiered in Zürich and Basel in 1915.

Suter's friend the composer-conductor Siegmund von Hausegger (who, according

to Adriano, wrote a splendid Natur-Sinfonie) conducted the work

in Berlin in 1916. Performances also took place in Hamburg (1917) and

Leipzig (1918).

After a rather overcast and unruly nebuloso and

marziale e fiero first movement in which the exemplar is surely

Richard Strauss comes a witty and bombastic Capriccio militaresco.

The brass choir have that commanding ruptured aureate tone that mediates

the defiant and the heroic. The glowing prayer-like adagio has

writing for the violins that may well have coloured Othmar Schoeck's

Sommernacht. The Rondo finale has a modicum of the levity of

the second movement coupled with a romantic striving that sounds like

a strenuous Schumann. The brass are recorded with satisfying emphasis

so if you love brilliantly recorded trumpets, trombones and horns you

must not miss this even if a certain heaviness afflicts the finale.

The mood changes from movement to movement spell an eccentric work.

Otherwise this is certainly something to enjoy.

Suter was a pupil of Huber. He found a modern intensity

of expression that eluded Huber almost completely. Our appetites have

now been sharpened by the experience of the Symphony to hear the 1921

Violin Concerto as well as the highly regarded oratorio, Le Laudi

di San Francesco d'Assisi.

The three pieces by Jelmoli follow after too short

a gap. They are the equivalent of the light incidental music of Roger

Quilter and Norman O'Neill in England or of Massenet and Fauré

in France. This is music written in the nature of an intermède

or entr'acte. One can easily imagine Beecham falling for the elegant

charm of Jelmoli's Intermède Lyrique.

An idiosyncratic Straussian symphony contrasted with

a bonne-bouche suite. Both novelties.

Rob Barnett