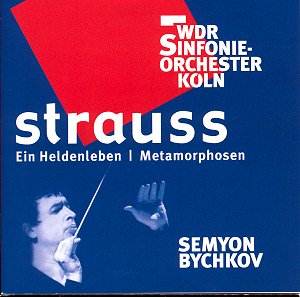

The enterprising Avie label continues to get the big

names on board. Hot on the heels of Jose Cura’s Rachmaninov Second

Symphony comes this excellent release. I had begun to wonder what

had happened to Semyon Bychkov’s recording career; I still play his

debut disc, a subtle, thoughtful and beautifully characterised account

of Shostakovich 5 with the Berlin Philharmonic, released on Philips

in the late 1980s. The booklet note tells us he has been active in the

recording studio as well as the concert hall and opera house, but in

truth his discography is relatively small for someone who seemed to

have a glittering future. Maybe this disc of mainstream favourites will

do the trick.

Of course, this disc is entering a very crowded field,

and both pieces have been well served on record since the earliest days.

There are numerous recommendable versions, but the coupling is rare,

and it makes excellent sense, the swaggering confidence of Heldenleben

contrasting most movingly with Metamorphosen, that disillusioned,

elegiac outpouring of his final phase. This is something Bychkov clearly

understands, and the disc is best heard straight through as a programme.

I played it four times on the trot, and can only say that I admired

the playing and conducting more with each hearing.

Bychkov’s intelligent musical mind is at work from

the start, and he makes the listener see (or hear) the bigger picture,

refusing to play to the gallery or give us odd moments in ‘technicolour’,

of which some versions are guilty. That’s not to say there isn’t excitement

aplenty, but it is cumulative, and therefore more effective. The gloriously

broad opening melody, which sets the tone for the whole piece, is paced

to perfection, its contours and shaping underpinned by exquisite phrasing

and dynamics. The music swells and relaxes, really breathes, and the

strings are encouraged by their conductor to give and take as one, almost

like a chamber ensemble. The critics carp beautifully in section 2,

and I doubt if there could be more characterful or sweet-toned solo

violin playing than Kyoko Shikata’s in section 3, ‘The Hero’s Companion’,

an affectionate but waspish representation of the composer’s wife, Pauline.

Shikata covers the gamut of emotion, and Bychkov follows her at every

turn – he must be a wonderful concerto partner. ‘The Hero’s Deeds in

Battle’ (section 4) may at first strike one as under powered, until

you realise that other versions are overdoing the drums at the start

(usually helped by false highlighting in the recording). Bychkov is

exciting, but is looking forward symphonically, and when the opening

theme is recapitulated (track 4, 6’20) we know just where he was heading.

As mentioned above, he integrates everything, so when we get the big

Don Juan horn theme quoted (track 5, 1’05) it is a telling episode

of recollection in our hero’s life, rather than a cute bit of showing

off. The end is truly moving, and never in this performance did I feel

(as I have done with others) that the composer is wearing his heart

on his sleeve.

The last section of Heldenleben is titled ‘The

Hero’s retirement from the world and the fulfilment of his life’, and

though we know it to be a self-portrait, listening to the opening of

Metamorphosen immediately after tells the true story. Bychkov’s

line of thought is the same as Heldenleben, and no less effective.

This is a ‘ lament without end … a choral lament without human voices,

only melody …’as the booklet has it, poetic but true, certainly in this

performance. It is a tricky work to really bring off, and this is the

best account I have heard since Rattle’s Vienna version, one of the

best reasons for buying his Mahler 9 (EMI). The strings of the WDR orchestra

do indeed become Strauss’s beloved voices, and they sing with such passion

and commitment that the spell cannot be broken until it has to be, at

the very end, when we get the famous quote from that other great lament,

Beethoven’s Eroica. It is a draining but memorably moving experience,

a half-hour journey that encapsulates the tragedy of a nation and its

culture, and how appropriate that is at the moment!

The playing of the WDR orchestra definitely contributes

to the enjoyment of the whole. Without their commitment (or indeed ability),

Bychkov’s vision would be severely diluted. As many of us know from

Rudolf Barshai’s stunning Shostakovich cycle, this is an orchestra to

be reckoned with, and Bychkov, who has been in charge since 1997, has

shown what a superb technician, trainer and all round inspiration he

can be. The string tone lacks nothing in comparison to Rattle’s VPO,

and the Heldenleben playing certainly outshines the sometimes

scrappy offering from Ashkenazy’s Cleveland forces on Decca. The recording

quality is superb, fully capturing the now famous acoustics in Cologne.

There is so much more to enjoy here than many of the

high profile, virtuoso run-throughs we have had to get used to. It is

deeply felt playing, guided by a conductor whose searing musical vision

and love of the pieces shines through every phrase. Even if you have

other versions of these glorious works (as any Straussian will have),

you will not regret getting this one.

Tony Haywood

![]() for details

for details