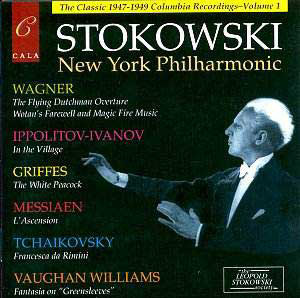

The recordings gathered here all come from the period

(1946-1950) when Leopold Stokowski was especially closely connected

with the New York Philharmonic as its Guest Conductor. In the very interesting

liner notes a contemporary member of the NYPO describes him as "authoritarian

and unyielding in his demands". As these recordings show the orchestra

was more than capable of fulfilling those demands. It’s worth quoting

a comment by another member of the orchestra from that era. In the notes

accompanying the fascinating CD collection, The New York Philharmonic,

the Historic Broadcasts, 1923-1987, John Ware (trumpet, 1948-88)

recalls "to me the orchestra always sounded warmer with him than

with anyone else. It had an intensity and emotional contact, and the

free bowing gave the strings an unusual legato quality." I’d say

that the second sentence of that recollection is borne out amply by

what we hear on this CD.

Certainly the intensity and emotional contact are fully

on display in the ‘Flying Dutchman’ overture (track 1). This is a bracing

and fiery opening to the disc, yet it is one in which the cantabile

sections are done equally well. The other Wagner offerings, ‘Stoki’s’

arrangement of ‘Wotan’s Farewell’, followed by the ‘Magic Fire’ music

(track 8) are no less impressive. I had feared that the Farewell, shorn

of its vocal line, might be a strange experience. In the event the sheer

verve and majesty of the playing compensates amply. Perhaps this item

is not for the Wagner purist but sample, if you will, the amazing build

up of volume (and tension) from 2’35" to the great moment of release

at 3’35"; this is a master conductor at work. The entire performance

is distinguished by refulgent strings and noble brass and I thought

it very fine.

I have some reservations about the Messiaen. This was

the first recording of the orchestral version. Indeed, it may well have

been the first recording of the work in either form since the composer’s

own recording of the organ score itself was not made until 1956 and

I am not aware of any earlier versions. One cannot but admire the enterprise

of Stokowski (and Columbia) in recording such a work a mere 16 years

after its completion for this must have seemed a very daring not to

say arcane choice of repertoire at the time.

I have to say, however, that I find the tempo for the

opening movement (‘Majesté du Christ demandant sa gloire à

son Père’) anything but majestic. Indeed, it is so brisk as to

seem perfunctory (track 3). Stokowski dispatches this noble chorale

in a mere 2’43" where Messiaen himself in his own (organ) recording

takes 6’47". The composer’s broad and stately conception seems

not a second too long. The second movement (‘Alléluias sereins

d’une âme qui désir le ciel’) is also much brisker in Stokowski’s

hands than under Messiaen’s fingers (4’16" against 7’57")

but in this case I prefer Stokowski’s approach and he conjures up some

mesmerising sonorities from the orchestra (track 4). The third movement

(‘Alléluia sur la trompette, alléluia sur la cymbale’)

exists only in the orchestral version for Messiaen wrote a completely

different movement, ‘Transports de joie’, for the organ version. The

performance by Stokowski and the NYPO is full of exuberant virtuosity.

The concluding ‘Prière du Christ, montant vers son Père’

(track 6) is echt-Stokowski, scored as it is for sumptuous strings.

Once again, he is much faster than the composer, taking 4’46" whereas

Messiaen weighs in at 9’18". However, in this instance I think

both approaches are right. Messiaen can and does justify his extreme

tempo in the context of an ecclesiastical acoustic and with the sustaining

power of the organ. Stokowski, I think, makes an equally correct choice

for strings in the concert hall. Though I have a major reservation concerning

the first of the four movements (which others may not share) the remainder

strikes me as a very fine account.

In 1958 Stokowski made a recording of Francesca

da Rimini (his second) with the Stadium Symphony of New York (a

contractual alias for the NYPO, I believe). That performance, coupled

with an equally fine one of Tchaikovsky’s Hamlet constitutes

what is, quite simply, the most incandescent recording of that composer’s

music I have ever heard. (I have it on dell’Arte CDDA 9006.) To be candid,

this 1947 recording, though it has much to commend it, is not in the

same league. The conductor secures virtuosic playing on both recordings

but in 1947 his tempi in the turbulent allegro music, so urgent and

involving in 1958, here seem just a bit too hectic (though the NYPO

is fully up to the challenge). It’s tremendously exciting but the 1958

reading is positively electrifying. The central love music is played

with all the passion you’d expect from Stokowski but even here I think

he has more to offer in 1958. Then there’s the question of the text.

In 1958 he gave the score complete but Richard Gate tells us in his

liner notes that in 1947 the maestro "made a number of brief cuts

in the ‘storm’ music on the grounds that the bars he cut were repetitive."

These cuts and the quicker tempi mean that this 1947 reading takes 18’56"

against 23’12" in 1958. Personally I prefer the later version but

there is plenty of magnetism in this 1947 account also.

The remaining short pieces are all well done. The Ippolitov-Ivanov

is, frankly, a trifle of Russian-oriental hokum but Stokowski relishes

every second of it. The Griffes work, premiered by Stokowski in 1919

during his Philadelphia days, is similarly not a piece of great substance

but once again the conductor lavishes great care on it and secures some

pretty marvellous playing from the New Yorkers. I was interested to

find that the Vaughan Williams ‘Fantasia’ was the original coupling

for Stokowski’s world premiere recording of RVW’s Sixth Symphony (which

he recorded on the same day, 21 February 1949, just two days before

Boult made his first recording of the piece in London.) That Stokowski

reading of the symphony has always seemed to me to be a bit underrated.

Of course, the music of the Fantasia inhabits a completely different

world. It finds Stokowski at his most lyrical, playing the gorgeous

main melody for all it is worth.

To sum up, this is a most interesting collection. Cala

have done a first rate job with the transfers and the original sound

is pretty remarkable for its age. Richard Gates’ notes are excellent.

I enjoyed this compilation hugely and have no hesitation in recommending

it.

John Quinn

see also review

by Jonathan Woolf