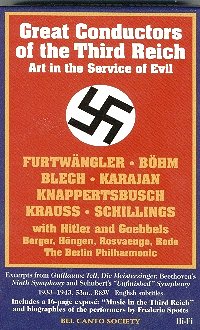

VIDEO REVIEW: Great Conductors of the Third Reich – Art in the Service of Evil

Furtwängler; Böhm; Blech; Karajan; Knappertsbusch; Krauss; Schillings, Berlin Philharmonic

Footage from 1933-1943, 53 minutes (NTSC or PAL) B & W – English Subtitles

BEL CANTO SOCIETY, BCS – 0052

Music in the Third Reich still holds a fascination for many people and watching some of the astonishing footage on this video it is not difficult to see why. We have Furtwängler conducting in a munitions factory and Karajan conducting in Paris after the German invasion with tanks still rolling up the Champs Elysées. Goebbels is omnipresent, shaking conductors warmly by the hand (particularly Böhm). Hitler is seen at the opera. It is not quite the same form of propaganda that Leni Riefenstahl brought to her masterpiece, 'Triumph of the Will', but sits very close to it.

Music has always had an important role to play in wartime, an oasis of culture placed side by side with human and cultural destruction. Is there really any difference, however, in Furtwängler conducting Beethoven to workers in war-torn Germany and Dame Myra Hess playing Schubert and Beethoven at the National Gallery as the bombs fall on London? In the simplest of contexts the answer is 'no', but the arguments have been complicated over the years by how far German conductors who remained in Germany conspired with and advocated the policies of the Reich. In the case of Karajan the French seemed easily forgiving since in the 1970s they appointed him as head of the Orchestre de Paris – even though he had conducted the Berlin Philharmonic in occupied Paris with what then seemed like a very militaristic conducting style. Concerts in Scandinavia, with Sir Malcolm Sargent also on the podium, were less popular when conducted by Germans – leading Karajan to tell Sargent that when Hitler arrived in London he would be shot. Yet, Karajan escaped lightly compared with some – and not without a little help from Walter Legge who brought the young firebrand to London to record and play with the Philharmonia. Karajan used the Nazi Party as a springboard for his own ambitions – and they used him because of his growing stature as a conductor.

Karl Böhm poses more of a problem. Appointed in Dresden, with Hitler’s approval to succeed Fritz Busch, he was both privately and publicly a Nazi apologist – and always gave the Nazi salute at the beginning of concerts he conducted. After the war he remained unrepentant believing that he had taken the difficult option of remaining in Germany when many had fled. Yet, his close artistic relationship with Richard Strauss bore extraordinary fruits and after a two-year allied ban he was appointed head of the Vienna State Opera. Knappertsbusch, despite his fervent nationalism, was largely considered to be inept by Hitler – to such an extent that Hitler forbade Knappertsbusch to conduct anywhere in Germany after 1936. He conducted occasionally at Nuremberg – and also at Cracow at the invitation of Hans Frank the Governor of Poland. Max von Schillings would probably have become the most notorious conductor had he not died in 1933. Within two weeks of the Nazi take over Schillings had been appointed directly by Hitler to reorganise German cultural life – and he immediately expelled Jews and liberals from the Prussian Academy of Arts – Schoenberg included. Clemens Krauss, another apologist in the Böhm mould, succeeded Knappertsbusch in Munich. Leo Blech was for sometime the only Jewish conductor allowed to remain publicly at work in Germany – largely through the intervention of Göring. It ended with his refusal to be allowed back into Germany after 1937.

Furtwängler has been the focus of most comment on the Third Reich problem and suffered disproportionate punishment after the war for his decision to remain in Germany. As early as 1936 there had been some questions asked about the great conductor’s involvement with the Nazis – he was thought of as a successor to Toscanini at the New York Philharmonic but an offer was withdrawn (Barbirolli went instead). In the early days, Furtwängler did resist attempts to purge the Berlin Philharmonic of Jews and he continued to play music banned in the Reich – Mendelssohn and Hindemith, for example up until the late 1930s. Whether this was due to an assertion over his personal autonomy of the orchestra and its programming rather than a deliberate move to resist Nazi cultural policy is a moot point. Frederic Spotts’ liner notes (there is no commentary for this video) comments on Furtwängler’s repertoire during this period saying that he did little to promote Jewish composers such as Mahler or Schoenberg. This is true – but it is true of Furtwängler before, during and after the Nazi period. He performed Mahler’s symphonies quite frequently in the 1920s but never returned to them – and after the war only conducted and recorded Mahler song cycles. When he started performing again, in 1947, both Mendelssohn and Hindemith returned to his concert programmes – yet it also true to say that a favourite Nazi composer he unaccountably championed during the war, Pfitzner, almost disappeared from his concerts after 1947. And, Furtwängler’s concert programmes throughout his career were almost entirely made up from the Austro-German repertoire of Beethoven, Bruckner, Brahms and Wagner.

Spotts alleges in his notes that Furtwängler was ‘anti-democratic, anti-liberal, anti-Semitic, an enemy of the Weimar Republic and an arch conservative both in music and politics’. There are many possible replies to this. All conductors are authoritarian – they need to be and Furtwängler was certainly no less illiberal than Böhm or Knappertsbusch both on and off the podium. Böhm and Karajan certainly played more Second Viennese School music than Furtwängler but their age differences and post-war cultural differences made this almost inevitable. Klemperer, a Jewish conductor, also did comparatively little after the 1930s to promote Jewish composers he had championed extensively during his Weimar years. And like Furtwängler, Klemperer had an ambivalent attitude towards Mahler’s symphonies. It is surely a matter of personal taste and projection, rather than political motivation, which made these two conductors play music by some composers and not others.

Furtwängler’s anti-Semitism is overstated by Spotts (particularly when he seems willing to gloss over the supposed anti-Semitism of other conductors shown on this video). He quotes from unnamed sources yet at the post-war tribunal little direct evidence was brought against the conductor – and much was brought forward to show he had helped individual Jews. However, a memo from 1939 did state that Furtwängler had used the phrase, "that Jew de Sabata" in a derogatory statement made against the Italian conductor. It is surprising because Furtwängler considered de Sabata a personal friend and invited him every year to conduct the Berlin Philharmonic – yet the conductor’s recollection of the phrase was nebulous. Hans von Benda was asked at the tribunal whether he had heard that Furtwängler had assisted Jews and other persecuted minorities. His reply was, "I not only heard about it, he actually did it". The de Sabata issue perhaps raised more questions about Furtwängler’s personal views (which on the whole were well known) about Jews than it did to support the assertion that the conductor was rabidly anti-Semitic (which he was clearly not).

The music in this video is largely by Wagner – exclusively from Die Meistersinger. Beethoven’s Ninth is also heard in performances under Knappertsbusch and Furtwängler. The Ninth, a symphony eulogised by the Nazi’s as the embodiment of Aryanism and monolithic society, was almost as popular as the omnipresent Wagner. In Nazi propaganda Beethoven was promoted as an icon of the Nazi State – a nationalist who shared the German ideals of Lebensraum and freedom. The performances could not be more different: Furtwängler firing on all cylinders, a near hysterical performance from 1942, typical in conception to his famous wartime recording of the work from the same year, Knappertsbusch stately and broad in tempi, statuesque and architectural in the Klemperer mould. Yet, in both cases the intensity of the music making is memorable.

That is a common impression of all of the recordings on this tape. The music seems, in one sense, to have a political association, which perhaps makes for lurid viewing. Yet this is entirely a visual problem, which we do not experience with live CD recordings from the period where the anonymity of the audience is all but assured. Yet these performances are praised without referring to the political motivation behind the music making (listen to Karajan’s live Beethoven and Bruckner with the Prussian State Orchestra for example – some in remarkable early stereo). Some will find it easier than others to disassociate the music from the footage. Others will be horrified that humanitarian musicians of this calibre were able to bring themselves to make a political association between music and government. At the end of this tape you should feel that the music triumphs.

Bruno Walter, in a letter to Furtwängler dated January 1949, wrote: "Please bear in mind that your art was used over the years as an extremely effective means of foreign propaganda for the regime of the devil: that you, thanks to your fame and great talent, performed valuable service for this regime and that in Germany itself the presence and activities of an artist of your rank helped to provide cultural and moral credit to those terrible criminals or at least gave considerable help to them…in contrast to that, of what significance was your helpful behaviour in individual cases of Jewish distress?" It could well apply to every other conductor featured in this video.

Marc Bridle

This video can be ordered from the Bel Canto Society’s website www.belcantosociety.org in both NTSC and PAL versions.

Crotchet AmazonUK AmazonUS Amazon recommendations