The concept of this 1999 Norwegian production, based

on the troubled life of Grieg, is worthy enough. It uses two of his

compositions, both very personal: the Ballade and the String Quartet,

shown played in full before an unenthusiastic audience of publisher’s

reviewers. This concept is used as a background to a series of flashbacks

as the elderly Grieg looks back over his turbulent life. I surmise that

in trying to satisfy an international audience, the producers decided

to eschew any commentary and dialogue in favour of an occasional quotation

from the off-screen "voice of Grieg." The trouble is that

these quotes, spoken in such a whisper, and in over-awed tones by Derek

Jacobi, are so infrequent that they are of limited assistance in fathoming

out the story to one’s complete satisfaction. Too much is left to the

imagination. For instance, we recognise - just – glimpses of Tchaikovsky,

Liszt and Brahms (the latter, I think, rather puzzlingly holding a paint

brush) in salons and other gatherings, but there is little, or no explanation

of their significance in Grieg’s story

The photography is sumptuous: beautiful views of Norway,

Germany, Italy and Denmark. Staffan Scheja is persuasive in his mute

acting role as Grieg, as a man, (Philip Branmer plays the boy Grieg)

but he is constantly upstaged by the more animated and beautiful Claudia

Zöhner as his long suffering and neglected wife Nina. The music

is sensitively blended with the on-screen story taking us jerkily backwards

and forwards through the composer’s life. We witness Grieg’s boyhood,

his loving relationship with his mother who was also his first music

teacher, and the overshadowing jealousy of his brother John. We see

his student days and his close friendship with Rikard Nordraak who died

tragically young in Berlin, and his love affair and subsequent marriage

to his cousin Nina Hagerup. The scenes of their courtship are lyrical

and beguiling. But the music becomes anguished as the on-screen images

show death taking his parents and the infant child he adores, and as

he realises Nina’s infidelity. The music is disturbed as he himself

succumbs to the painter Sabine Oberhorner and as Grieg’s obsession with

his music and his busy touring schedules deepens and becomes all pervasive.

You are left with an impression of a life unfulfilled – as Grieg, himself,

put it "a life fractured" by so much tragedy.

A worthy concept filmed in glorious locations with

more than acceptable mute acting but just that bit too enigmatic for

complete satisfaction.

Ian Lace

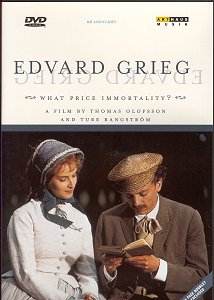

![]() Edvard Grieg………………..Staffan

Scheja and Philip Branmer

Edvard Grieg………………..Staffan

Scheja and Philip Branmer ![]()

![]() ARTHAUS

MUSIK DVD Video 100 236 [77 mins]

ARTHAUS

MUSIK DVD Video 100 236 [77 mins]