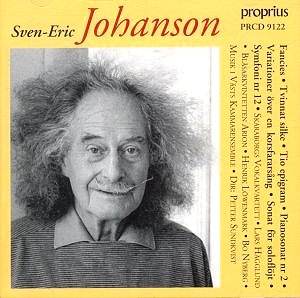

Sven-Eric Johanson, a composer in his sixties,

stares out at us with wild hair and Dali-esque waxed moustachios,

from the cover of this 1995 issue from Proprius. We are not given

his date of birth as far as I can tell from the Swedish-only notes.

He has written prolifically including twelve symphonies and the

Saga of the Rings (after Tolkien). His range can perhaps

be perceived from these pieces from which we may guess that he

has a quirkily humorous and certainly effective approach to writing

for voices as in the nine Shakespeare Fancies which are

for four voices and an audaciously adventurous piano which makes

light of fragments of Grieg's Spring in Lovers Love

the Spring and in other songs with Beethoven's Fifth Symphony.

These English language settings remind me of Geoffrey Bush's pacy

and lively vocal settings as in the wonderful Summer Serenade

(try it on Chandos) and Hesperides.

The nine Shakespeare songs are Sylvia;

Under the greenwood tree; Blow blow thou winter wind;

Fancy; O mistress mine; Lovers love the spring;

Winter; Dirge; Hark hark the lark. These

songs have most recently been recorded on a Danacord collection

of Shakespeare settings although there a full choir is used. Here

the definition and word enunciation is more sharply etched.

After two choral works of the 1970s Proprius

proffer two works for solo piano from the 1950s. The Ten

Epigrams (each separately tracked) are brief lively Schoenbergian

essays, terse, tending to a sort of liquid free-flowing impressionism

mostly dreamy with a single outburst in the tempestuous little

Eighth Epigram. The Sonata is an unforgivingly discontinuous

exercise declaring unreservedly its credentials from the 'plink-plunk'

school. The Epigrams are more approachable. The Sonata

for solo flute occupies the same territory as the Epigrams

and in the third movement even tries its hand at levity.

Leaving the Schoenbergian domain Johanson sweeps

forward to the demure and flavourful Variations on a Crusaders'

theme for wind quintet. These are banded as a single track. These

demonstrate harmonic complexity but are highly melodic with flavours

of Iberian medieval instrumental ensembles mixed with Stravinsky's

Symphonies for Wind Instruments - nothing more intimidating

than that. The Variations end with the softly rounded crusaders'

theme stated in melodious harmony bringing the Variations full

circle.

The Johanson symphonies include No. 1 Sinfonia

Ostinata (1949), No. 5 Etemenanki (Elements Symphony)

and No. 8 Frödingsymfonin for soli, chorus and orchestra.

The Twelfth Symphony, dedicated 'in memoriam Arnold

Schoenberg' is designated by the composer as a 'chamber symphony'.

It is in four movements and especially in the outer movements

tramps dissonant foothills combining a sun-dappled atmosphere

with the lyrical warmth Johanson seems to have found since the

1980s and with which he has always been in touch in his vocal

works. Solo instrumental lines emerge and float free in neo-Baroque

concerto grosso style. In the third movement allegro scherzoso

a helter-skelter chase is painted in chatter and rattle.

A switch-back ride through the wildly varied

realms of a Swedish composer just as home in tangy Schoenbergian

motley as in the modern zany choral tonalism.

Rob Barnett