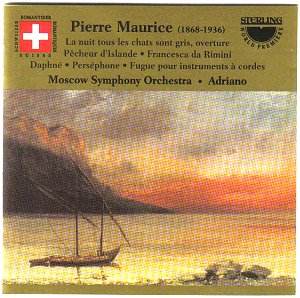

Maurice

was born on the shores of Lake Geneva. He studied music in Stuttgart

with Percy Goetschius and settled in Munich for twenty years from

1899. During the Great War he was in charge of music at various

POW camps. In 1919 he returned to Switzerland. There are operettas,

oratorios, song cycles with orchestra, ballets, overtures and

operas in the Maurice worklist.

The

overture to the 1932 operetta La Nuit tous les chats sont

gris is at first a restive playfully flickering reflection

of John Foulds' overture Le Cabaret with brilliant work

for brass and woodwind. Later it yields to ecclesiastical and

then impressionistic musing on the French folksong Au clair

de la lune. A cock-crow summons the Berliozian brilliance

of the opening - a Roman Carnival or Benvenuto Cellini

indeed.

Both

Guy-Ropartz and Maurice were drawn to write music inspired by

Pierre Lôti's Pêcheur d'Islande. Maurice's

four episodes make an early impressionistic suite. The introspection

of Sur La Mer d'Islande is reminiscent of the Bachian devotions

of Saint-Saëns' prelude to La Déluge with an

insistent figure that might well have stuck in the memory of Mario

Nascimbene when he wrote the main theme for the film, The Vikings.

After grim intimations come bucolic themes with much cheery work

for the woodwind. I am not sure that such stark contrasts work

well. The mellow slow wash of Propos d'amour is much more

successful with its sustained sunset glow. L'attente sur la

falaise (keeping watch from the coast) glows and glowers rather

than howls. If this atmospheric suite has a weakness it is its

emphasis on mood over drama. It does however go to show that Maurice

was a composer of sensitive integrity.

Almost

a quarter of a century after Tchaikovsky's overwhelming Francesca

da Rimini, Pierre Maurice wrote his own 'symphonic poem after

Dante'. This is a work potently eloquent in its depiction of mood.

It has some well-spun love music which has Tchaikovskian resonance

(6.34) and, as Adriano's notes suggest, it is also a burnished

invocation to darkness. It is of a type that we find in the gloomy

prelude to Bernard Herrmann's music for Citizen Kane as

the camera tracks through the ruined dreams of Xanadu.

After

the Daphné Prelude, with its Hansonian theme and

faintly impressionistic treatment, comes the latest work in this

collection; another piece inspired by Greek legend. Perséphone

is strangely Straussian in its writing for the horns but then

reverts to type with smoothly undulating themes carrying a suggestion

of George Butterworth when animated and of Delius or Bantock (Pierrot

of the Minute - a work to receive a new recording from Hyperion

later this year, 2003) when reflective. Perhaps early Roussel

(Dans la forêt) and D'Indy (Jour d'été)

would be closer parallels. This is a work of instinctive meandering,

rhapsodic temperament and perhaps occasionally loses the plot.

To compensate there are some revelatory moments such as the murmuring

strings at 7.21. The second movement of Perséphone

takes us back into Herrmann territory. Who knows, Bernard Herrmann

might have given Maurice an outing or two during his incredibly

varied NBC studio broadcasts in the 1930s. This is also the sort

of music that would have appealed to Constant Lambert and still

more to Sir Thomas Beecham. Relief from the gloom of Perséphone's

enforced exile to Hades comes at 5.43 in the second of the two

movements.

The

Fugue for strings is well-rounded, almost voluptuous, and

certainly defies the academic dust that normally settles on such

creations.

Not

desperately compelling music but surely there is room in the world

for such sincere romantic-impressionist creativity.

Rob

Barnett

see

also review by Michael

Cookson