Many

of you remember early experiments at recording the clavichord.

Thurston Dart, Ralph Kirkpatrick and Igor Kipnis all produced

on LP clavichord versions of baroque classics, and all such recordings

are gone, and a good thing, too. They sounded awful and nothing

like any clavichord I ever heard. And I should know, having owned

a clavichord for more than 30 years and having struggled unsuccessfully

for much of that time to learn to play it with any facility.

The

problem is that the clavichord is really quiet. I mean really,

really, REALLY quiet. Sticking the microphone

close in creates a false sound not because the volume is raised

but because noises in the instrument that normally fall below

the threshold of hearing are made audible, and they seriously

detract from the music. Trying to bring out only the music and

suppress the noises leads to draconian acoustic and electronic

filtering regimes, so much so that I have always felt that it

would be better to use a synthesiser and recreate the experience

of hearing the clavichord entirely from scratch.

Why

now do we have so many really good clavichord recordings? Is it

because we know more about recording now? No, I don’t think so.

I think that the instrument has simply been redesigned so that

modern piano technique can be used on it, and all the old clanks

and scrapes and wobbles simply don’t occur. In other words, we

have good clavichord recordings because the clavichord used is

one Bach would not recognise. In a way we have synthesised the

sound, but mechanically rather than electronically. A clue to

this is the date of the model for Mr. Adlam’s copy. By 1763 the

clavichord was engaged in a death struggle with the pianoforte

which, having nearly finished devouring the harpsichord, was now

hot after the clavichord as inexpensive and much easier to play

pianofortes suitable for middle class homes began to appear. Such

"improvements" as were possible to stabilise the clavichord

sound were being implemented. I would like to hear Mr. Adlam play

a single brass strung fretted clavichord from 1663.

I

actually attended a clavichord concert once. The performer (the

man who had sold me my clavichord) had spent his whole life learning

three pieces, and the audience (there were 9 of us) heard his

whole repertoire. Fortunately they were short pieces because the

entire audience had to hold his or her breath throughout, with

breathing and squirming—heaven forbid coughing!—only permitted

between pieces. This instrument was a single strung instrument

with full bebung, which means that the performer had complete

control of the pitch of every note at every instant, hence every

kind of tremolo and vibrato could be used, resulting in an ethereal

singing quality comparable only to a violin, perhaps with echoes

of a koto, and quite unlike anything on this disk.

Well,

this koto is now strung with iron wire. The new clavichord is

ganz bebungfrei. It sounds as if the keys bottom into a

kind of space age plastic which totally damps the clunk while

clamping the pitch within a microHertz, and the keyboard is likely

also acoustically isolated from the sounding box by another space

age plastic or computer designed vibration isolation mechanism,

although I have heard that a stack of paper punchings can also

be effective. The amplified transient, which can sound just like

a galvanised garbage can (that’s a tin dusbin to friends in the

UK) falling down concrete stairs, has somehow been miraculously

stifled. The result of these improvements is that one’s clavichord

touch is no longer forever ruined by five years of piano studies,

and we hear something that sounds wonderful and not unlike a clavichord,

although if Bach pére and/or fils were in

the audience, they would curl their lips and look very askance.

But

who’s complaining when the music is served so well? We are presented

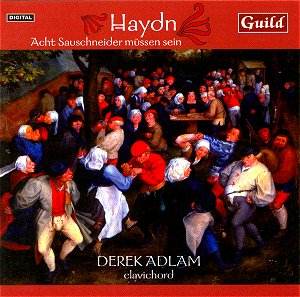

with three Haydn keyboard sonatas and three sets of variations.

As the commentator (D.A. Welbeck) points out, Haydn is remarkably

under rated, and this music confronts us with the terrifying possibility

that it’s all so good we might have to hear all of it, a prospect

best left, as in my case, to retirement years while living near

a large university music library. Instrumental concerns aside,

these are superb performances of the music, the best I’ve heard

on any instrument. The performer has as thoroughly mastered the

music as he has the instrument, and the variety of volume levels

and textures available to him have been effectively utilised.

This shows most strikingly in the variation sets which will be

new to most of us, and further demonstrate Haydn’s astonishing

and wide ranging genius. It is to be hoped Adlam will continue

to record more of these works for us, and set a new standard in

Haydn interpretation, aesthetically and sonically.

Paul

Shoemaker

A

response from Derek Adlam

A bad experience early in life can leave an indelible

mark on us. Mr Shoemaker seems to have been scarred for life by

a bad clavichord with a thin, trembling sound barely audible above

the clatter of ill-fitting keys.

It's true that there have always been bad clavichords around.

A late 17th century writer complained about instruments where

the listener hears more wood than wire, but consoles us by adding

"they are good to burn when one wishes to cook fish".

A good clavichord on the other hand has a quiet action and a

full, singing sound that responds to the player's hand like no

other contemporary keyboard instrument. This is true for all types

of clavichord from the earliest made near the beginning of the

15th century to the end of the 18th.

For my Haydn recording for Guild (GMCD 7260) I used a copy of

a 1763 J. A. Hass clavichord made in my own workshop. This is

a careful reproduction of a fine historical instrument. It makes

no concessions to modern materials: the idea behind such a copy

is to provide a present-day player with a "tool" exactly

like those familiar to composers such as Haydn. And J. S. Bach

and his sons would have known instruments very like this one.

So no plastic bushings, no modern widgets, no "improvements":

they're not needed. Nothing to get in the way of a player's search

for the way to speak a composer's language -- finding the grammar,

vocabulary, intonation and inflection of his voice.

In this and other good modern recordings of the clavichord there's

no need for technical funny business -- no electronic tricks,

no falsification, no lies. This is what fine clavichords actually

sound like. Perhaps Mr Shoemaker should look at his own clavichord

in the light of these comments and prepare to cook some fish?

(But many thanks for the nice remarks about my playing on this

disc. It's marvellous music.)

Derek Adlam, Welbeck, Nottinghamshire, U.K.