Though he wrote a good deal of vocal music, including

several large-scale choral pieces such as the majestic Mass

Op.130 (1945 Ė soloists, chorus, organ and brass), his prize-winning

cantata Comala Op.14 (1897 Ė soloists, chorus and

orchestra, which will soon be available on disc) as well as several

choral works with or without accompaniment, Jongen only composed

thirty songs (eight of them are unpublished and possibly withdrawn

by the composer) of which the present release offers a generous,

if incomplete selection. (Deux mélodies Op.29 of

1906, Les pauvres Op.64 of 1919 on a poem by Verhaeren

and Bal des fleurs Op.25 No.4 have not been included.)

Most of his songs, originally for voice and piano, have been orchestrated

by the composer, who also made most of them available in a chamber

version (voice, piano and string quartet). However, though not particularly

abundant, Jongenís songs are far from negligible and are particularly

attractive in their orchestral guise.

The earlier songs here, Deux mélodies

Op.25 of 1902 and Deux mélodies Op.45

of 1914, are still redolent of, say, Fauré or Duparc, and

none the worse for that. The original Op.25 cycle consists of

four songs. Three of them were orchestrated in 1922 and two are

heard here (Après un rêve on a poem by Romain

Bussine and Chanson roumaine on a text by Hélène

Vacaresco). Though still fairly traditional, these songs are as

beautifully written as anything else in his output. Deux

mélodies Op.45 (1914, orchestrated 1922) set a

fine symbolic poem by Franz Hellens (Les cadrans) and a

poem by Jules Delacre (Que dans les cieux). They are quite

similar to the earlier songs, although the much finer literary

quality of the texts (especially that by Hellens conjuring-up

some mysterious visions) drew a superb musical response on Jongenís

part.

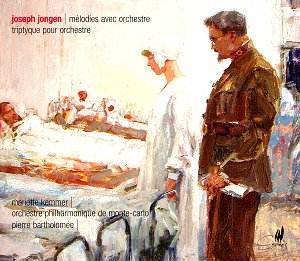

However, Cinq mélodies Op.57,

completed in 1917-1918, is one of Jongenís crowning achievements

and a real masterpiece. Originally, Jongen planned to set Hellensí

war poems Les fêtes rouges, but eventually did not

set the fourth poem. Hellensí poems, for all their Christian symbolism,

express a dark, sometimes ironic vision of warís atrocities and

are conspicuously free of any jingoism. Rather, the harsh realities

of war depicted in LíEpiphanie des exilés (symbolised

as the three Magi), still more forcefully in Le carnaval des

tranchées in which the soldierís bride (i.e. Death)

is described as "pure and gloriously beautiful" and

finally in Langues de feu (in which the apostles are called

upon to go and preach Ďjust hatredí), are echoed by some powerfully

impressive, at times grotesque, always gripping music. The cycle

is completed by two songs of a more tender, gentle character offsetting

the tension of the preceding songs and thus providing this impressive

cycle with an appeased, though by no means serene conclusion.

Triptyque pour orchestre Op.103

is a much later piece completed in 1937. To some extent, this

substantial work pays a direct and sincere homage to Debussy and

Ravel, whom Jongen admired and who were among his models. At times,

the homage goes as far as alluding to the French composersí music

or even briefly quoting from it. Jongen, however, remains his

own self, and the music is vintage Jongen throughout. The opening

movement moves along quietly, dreamily, almost seamlessly so.

The central Scherzo is Jongen in his outdoor mood, skipping along

with infectious energy and briefly alluding to Debussyís Fêtes.

The final movement reverts to the contemplative mood of the opening

one. It opens mysteriously, redolent of the dawn section from

Ravelís Daphnis et Chloé, but the music then

goes on in Jongenís own (musical) terms. This much neglected work

is one of Jongenís finest, most colourful and superbly crafted

pieces in which he effortlessly displays his remarkable orchestral

mastery. I had never heard this piece before, but I am now convinced

that it is a major, unjustly neglected work.

Excellent performances and recordings that serve

the music well. Mariette Kemmer sings beautifully throughout and

gets a superb support from the Orchestre Philharmonique de Monte-Carlo

that plays this much unfamiliar music most lovingly and convincingly.

CYPRES have already put us much in their debt for several outstanding

discs of Jongenís music. There is much to enjoy in this most welcome

release that I warmly recommend. My record of the month anyway.

Hubert Culot