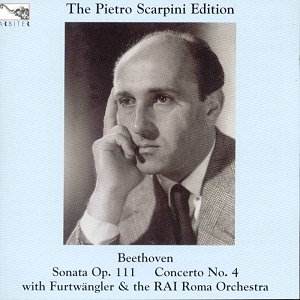

Arbiter

here inaugurates the first of their series dedicated to the under-appreciated

art of Pietro Scarpini (1911-1997). Devoted though he was to the

masterpieces of the repertoire – his recitals of the Diabelli

and Goldberg Variations were renowned – he also embraced Janáček,

Schoenberg and Dallapiccola, who was a good friend. Scarpini had

studied piano with Casella and composition with Bustini and Hindemith,

counting Molinari as his mentor in conducting – and it was the

latter who first conducted for him in 1937. His career grew after

the War and he travelled internationally but his name was not

widely known beyond connoisseurs. Part of the reason was his reluctance

to record and the mantle of Italy’s leading pianist had by then

been grasped – not that Scarpini would much have carried for the

gladiatorial aspect – to Michelangeli. It’s timely then that this

disc should appear and it shows Scarpini’s strengths in their

considerable depth.

The

Concerto performance was his only encounter with Furtwängler.

The sound is adequate to good and certainly not unpleasant but

it is somewhat constricted sonically, dating from 1952. The conductor

elicits some pensive and withdrawn orchestral statements from

the RAI orchestra, vesting the opening movement with a real sense

of volatile withdrawal. Scarpini has just the right degree of

lyric elasticity for Furtwängler’s kind of conducting and

gives a great freedom to the piano part, a flexible, spontaneous

sounding generosity of utterance. The Elysian flutes are here

answered by gruff piano entries almost foreshadowing the orchestral/solo

exchanges in the Andante con moto. There are certainly some mighty

accelerandi here as well as a tense series of dynamics. In that

slow movement one derives the feeling that this is less a dialogue

between orchestra and piano and more a kind of dramatic monologue,

of Shakespearean depth, in which by some alchemy it is as if the

piano were playing all the way through and it is we who fail to

hear. Though the outer movements are relatively slow, Furtwängler

gives impetus to the rhythmic material and it never seems unduly

slow. The conclusion isn’t especially neat playing but it is exciting

and powerful.

Coupled

with the Concerto is the Op.111 Sonata. From 1961 and in good,

quite close-up sound (one can sometimes hear the pedal), this

is a noble and acute performance that combines considerable richness

of tone with a superior analytic mind. His command of the rhetoric

is undeniable, the comprehensiveness and cohesion of the interpretation

admirable.

So

this is an admirable start to the Scarpini series. It comes with

some worthwhile documentation – a biographical note, a career

highlights compiled by Scarpini himself and a newspaper interview.

He seems to have been almost as elusive on print as he proved

to be on disc. Warmly recommended.

Jonathan

Woolf