In the days before commercial recordings piano

or organ transcriptions of orchestral or operatic music were often

the vehicle by which many people got to know works that we nowadays

take for granted. The arrangements presented here were made primarily

for another purpose, however.

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) founded the Society

for Private Musical Performances in Vienna in 1918 because he

was fed up of having to endure hostile and fractious behaviour

by some concertgoers when confronted with a new piece of music.

The frequent disruptive behaviour by a section of the Viennese

public compromised the appreciation of these new works by Schoenberg

and like-minded people. So he founded the Society with the aim

of presenting new music to a small but congenial and understanding

audience. It was impossible to present these performances with

a full orchestra (if required) so where necessary the music was

arranged either for piano(s) or for a small ensemble. All this

information, and much more, is contained in the very useful notes

accompanying this release.

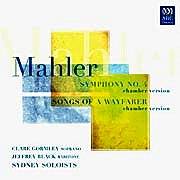

Mahlerís music featured quite prominently in

the Societyís programmes. Indeed, a two-piano version of his Seventh

Symphony was included in the very first concert. As well as the

song cycle arrangement included here Schoenberg made for the Society

an arrangement for small ensemble of Das Lied von der Erde

(which has been recorded both by Herreweghe for Harmonia Mundi

and by Mark Wigglesworth on RCA). The arrangement of the Fourth

Symphony was made by Erwin Stein (1885-1958) and he conducted

its first performance in 1921. When he left Austria for England

in 1938 the score and parts were lost and it was his daughter,

Marion Thorpe, who reconstructed the arrangement at the behest

of the Britten Estate, working from her fatherís annotated copy

of the full score. The reconstruction was heard for the first

time in 1993.

The scoring of the Stein version is indeed slender

compared to Mahlerís full orchestral dress. Just 11 players are

used. The instruments required are: two violins; one each of viola,

cello and double bass; flute (doubling piccolo); oboe (cor anglais);

clarinet (bass clarinet); piano/harmonium; and two percussionists.

Itís not clear whether Steinís scoring was voluntary or whether

it was dictated by the availability of players. I must say that

the omission of a French horn strikes me as particularly regrettable.

That instrument was always crucial to Mahlerís scoring and never

more so than in the Fourth Symphony where it has countless important

passages.

I must admit to some ambivalence about this recording.

I find the reduced scoring by turns enlightening and frustrating.

Carl Rosman makes a good case for the chamber version in his notes,

arguing that this version imparts a unique transparency to Mahlerís

lines and allowing many details to come through with far greater

clarity than is possible in the full scoring. To some extent Iíd

agree. However, surely the difference between now and 1920 is

that we know Mahlerís score so well. Iíll admit thereís a certain

piquant fascination in spotting where familiar lines have been

reallocated (and, on first hearing, in trying to guess which of

the instruments will get a particular solo, normally played by

an absent instrument.) However, the reduced scoring robs us of

Mahlerís complicated but very finely calculated orchestral palette.

Consequently, Iím bound to say that I found more instances of

frustration than of enlightenment when listening.

For much of the time the re-scoring is surprisingly

effective, no doubt because this symphony has the lightest orchestration

of all the nine. However, to make perhaps the most obvious point

of all, itís the climaxes that really suffer. Take the climax

of the first movement, for instance (track 1 from 9í12")

where the knifing trumpet part anticipates the first movement

of the Fifth Symphony. Here that critical motif is allocated variously

to clarinet, oboe and flute and Iím afraid I find it lacks conviction

in this guise. Worst of all is the great moment of fulfilment

at the climax of the third movement (track 3, 16í01"). Here,

above all, I felt short-changed. The sun just doesnít burst through

the skies here Ė how one misses the pounding timpani and pealing

horns!

There are passages of real felicity, however.

One such is the introduction to the final stanza of the poem in

the finale where Stein allots the line normally heard on muted

violins to solo flute to lovely effect (track 4, 5í33").

The perky, rustic scherzo also works quite well in this version,

though I miss the earthiness of the horns.

The finale features distinguished singing by

Clare Gormley, a singer new to me. She has a lovely tone and sings

with purity and a sophisticated innocence Ė Iíd like to hear her

sing the part with full orchestra. In fact, I found that this

movement works best in this performance, perhaps because the ear

is drawn to the singer rather than to the accompaniment.

This is true also of the song cycle (or perhaps

oneís ear is accustomed to hearing the songs with piano accompaniment?).

Here the scoring is even lighter, requiring just 8 players. John

Harding plays the sole violin part as well as directing the performance.

He is joined by one each of viola, cello and double bass. The

ensemble is completed by flute/piccolo, clarinet/bass clarinet,

piano and one percussionist. Jeffrey Black is an excellent soloist.

He has a heady, easy baritone and the wide tessitura of the cycle

gives him no problems. His diction is excellent (as is Clare Gormleyís).

These are charming performances of the songs, light and airy and

a delight to hear.

No praise can be too high for the standard of

the instrumental playing on this CD. The challenge of playing

a symphonic score in such reduced numbers is a daunting one but

the Sydney Soloists are superb. In these exposed scores there

are no hiding places but none is needed. The playerís technical

accomplishment and musical sensitivity are tremendous and they

serve Mahler and his arrangers exceptionally well. John Hardingís

direction of both pieces is sure footed. His are straightforward,

unmannered interpretations with no unwelcome or attention-seeking

quirks. In summary they are completely idiomatic. The performances

are presented in excellent, natural sound.

Although it undoubtedly served an important purpose

at the time I do have reservations about the arrangement of the

symphony and its relevance to todayís audiences. However, I have

learnt a lot from hearing it and Iím sure I shall return to it

in the future. Itís an enterprising and stimulating release but

one for the specialist listener only, I suspect.

John Quinn