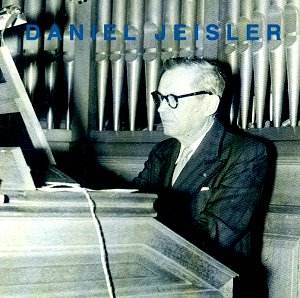

Born in 1877 in Klockrike, Daniel Jeislerís studies

took him to Stockholm, where he excelled on piano and organ but

it was in Paris that he spent the majority of his life. There

he met Saint-Saëns amongst others, cultivating friendships

and accompanying such artists as Ninon Vallin, Pablo Casals and

Jacques Thibaud. He was organist at the Swedish Church in Paris

for over forty years, inaugurating concerts and composing; four

symphonies, sonatas for cello (his wife was a well-known cellist)

and other chamber works as well as a large number of songs and

organ music.

His Introduction, chorale and variations for

organ dates from the last year of the First World War. Itís

an attractive work written securely in the French style with an

Andante section of powerful and gathering eloquence and intensity.

There are times though when, for all its security of technique

and musicianship, it does rather tread water. Given his knowledge

of the cello his idiomatic writing for it is only to be expected

and the 1921 First Cello Sonata, a big work in four movements,

is attractively wide-ranging in its freedom. The first movement

has an impressionistic burnish though it lacks a certain concision

of utterance, whilst the quick second movement is a playful one

and adopts a Ravelian cast in its mediation of the past with the

present. The old world baroquerie that Jeisler introduces co-exists

with scampering writing and amusing pizzicato episodes. Maybe

the players could have taken it quicker for optimum effect Ė itís

marked Molto Vivace. Jeisler has a long-breathed Adagio but itís

not really distinctive enough thematically and I preferred the

Finale, which opens musingly before developing some animated and

Brahmsian strength with nicely lyric edge.

The Five Songs vary from light, then-contemporary

folk style to the use of subtle barquetta rhythm. The most impressive,

harmonically, is Rafales díautomne, which would be more than worth

hearing in a recital set in its historical and geographical context.

Finally the Adagio for string orchestra, taken from a radio

broadcast, which is rather Mahlerian (No.5) though it develops

some sinewy and agitated writing along the way.

Performances are very sympathetic. There are

times when cellist Kerstin Elmqvist-Gornall is too backwardly

balanced in the Sonata but it matters very little since the playing

is enthusiastic. Soprano Kristina Furbacken has a light attractive

voice and does well by the songs. Notes are in French and Swedish.

Jonathan Woolf