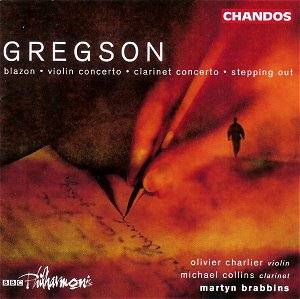

For impact, Gregson’s music, as demonstrated

by this CD, takes some beating. Edward Gregson is the Principal

of the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester, and as a

composer he has enjoyed a considerable reputation for thirty years

largely for a variety of vividly realised music for band, including

several concertos which have been variously recorded (notably

on the Doyen label). Some years ago now I encountered Gregson’s

Missa Brevis Pacem when my daughter played in it as a member

of the National Children’s Wind Orchestra, and it was immediately

apparent that here was a composer with the common touch of a Britten

in such music. One can only rejoice that Gregson has at last stamped

his personality on the wider orchestral repertoire with this very

successful Chandos disc.

The coruscating extended opening fanfares of

Blazon feature those aspects of the orchestra which Gregson

has always done best – brass and percussion. Paul Hindmarsh in

his excellent notes tells us that Gregson described Blazon

‘as a miniature concerto for orchestra’ which grew out of an earlier

piece, Celebration, for symphonic winds, harp and piano.

The orchestra is divided into concertante groups who each have

their own music. Gregson called one of his earlier works ‘Dances

and Arias’, a title which could apply to much of his music, and

certainly encapsulates this contrasted musical landscape, the

reflective atmospheric song-like instrumental interludes, perfectly

judged to reflect the general energy and brilliance. It allows

the BBC Philharmonic wind players to show their strengths, which

they do in uninhibited style. It underlines Gregson’s characteristic

strengths – the dance, the fanfare and the song-like line – which

constitute some of his most memorable invention.

BBC Radio Three habituées will remember

the broadcast of this programme from the Royal Northern College

of Music last February. I was at the concert and it was notable

at the time how immediate and exhilarating Gregson’s music was

in the hall. Now tidied up in the studio over the following two

days, with the soloists in perfect balance, here is music of today,

music of substance and wide communication which one hopes will

put the composer on the regular concert scene. The violin soloist

had a notable personal success with the audience in the hall,

though I must say I had not seen him before. Professor of violin

at the Paris Conservatoire for nearly 25 years, Charlier was the

soloist on Chandos’s earlier recordings of the concertos by Dutilleux,

Roberto Gerhard and Gerard Schurmann. The concertos both identify

closely with their soloists, and the soloists with them. Both

are on a substantial scale, running around half an hour. Both

exhibit a strongly personal voice.

Gregson’s fascination with the dance becomes

more and more intriguing, and it seemed to have reached a climax

with his choral work The Dance, Forever the Dance, a notable

success in 1999. The Violin Concerto comes from this same background

and has a programme suggested by three quotations that appear

above the three movements. For the first he quarries a quotation

from The Dance taken from Oscar Wilde: ‘But she – she heard

the violin, And left my side, and entered in: Love passed into

the house of lust.’ With such a tag we may expect both dances

and arias, and we are not disappointed. The violin soon arises

from the romantic atmospheric opening, which is quickly left behind

in the violin’s relentless figuration. Gregson’s high lying lyrical

line has momentary reminiscences of earlier twentieth century

concertos, by Walton, Samuel Barber and Prokofiev’s Second. Wilde,

in his poem ‘The Harlot’s House’, shows the woman preoccupied

by a distant waltz, and Gregson’s music reaches a climax with

an insistent dance macabre, reinforced by the ensuing cadenza

for violin and timpani. This runs on into the second movement,

still a dark and threatening atmosphere, which at first strikes

an autumnal note, this time with a quotation from Verlaine in

French, this is the English: ‘The drawn-out sobs of the violins

of autumn wound my heart with a monotonous languor’. Here Gregson’s

brooding strings presage one of the work’s high points as he continues

to explore the world of the first movement leading to a huge and

threatening climax before relaxing into the textures heard at

the opening of the first movement. Here the music achieves a passing

hard-won serenity as at the close of the movement the solo violin

sings deliciously over running harp figurations. The finale sets

out with what seems to be an Irish reel, albeit a Gregsonian version

of one, the superscription this time coming from Yeats (‘And the

merry love the fiddle And the merry love to dance.’) but this

is still a troubled world we are passing through. At one point

the muscular string music from Blazon appears, but although Paul

Hindmarsh’s notes tell us we have finally achieved general rejoicing,

this is still very much music of today evoking the world as it

is, there is to be no serenity.

The earlier Clarinet Concerto has a similar dramatic,

quasi narrative thread running through it, though without quotations

giving us any non-musical clues; the solo clarinet’s odyssey,

ultimately successful, is left to us to divine. This is a clarinet

concerto on a notably large scale, and in its wide-spanning argument,

symphonic in intensity and scope. It was commissioned by the BBC

Philharmonic for Michael Collins and first heard in 1994, and

it impressed then for its scale, for its approach centred on the

soloist and for its typical rhythmic closing section, capped,

as the composer tells us, by ‘the melody for which the whole concerto

has been waiting’. Clarinettist Michael Collins has really identified

with the music and he gives a remarkably personal and personable

account of the music.

The filler, Stepping Out, is a vigorous

string orchestra essay in minimalism which suggest John Adams.

Indeed, the booklet quotes the throwaway remark, presumably made

by the composer: ‘John Adams meets Shostakovich, with a bit of

Gregson thrown in’. In fact the second part, a tempestuous fugue,

is pure Gregson in its drive, excitement and no-nonsense cut off.

If you have not come across Gregson before do

try this approachable and eloquent music. The BBC Philharmonic

production team of Mike George and Stephen Rinker have done a

great job for Gregson and Chandos.

Lewis Foreman

see also Concerto

for Orchestra