There can be little doubting the fact that the

story of Alceste or Alcestis, as found in Greek mythology, was

one of the most popular stories used in opera in the 17th

and 18th Centuries. In the present climate where obscure

and sometimes rather mediocre late baroque and classical operas

and Singspiels are being dug out it was inevitable that another

Alceste would emerge. This present work is a singspiel, a form

much in popularity in Germany, particularly Leipzig and Salzburg

in the 1770s and 1780s. It was much graced by Mozart with pieces

like ‘Il Seraglio’ but its popularity spread to Mannheim, Dresden,

Hamburg and even to Prague.

But what of Schweitzer and Wieland. They are

given equal weight in the CD booklet and essay so that at first

I thought, as I was ignorant of their existences, they were a

kind Rodgers and Hammerstein. Their biographies are given in the

aforementioned notes. It seems that in fact they hardly worked

together at all. So, with the exception of two smaller projects,

this work is pretty well a ‘one-off’. Wieland was much the more

famous. As he admired Schweitzer’s music so much and regarded

the rendition of his text as of paramount importance we must see

this work as an important phase in the development of German theatre

and opera. In any case, its immediate success and the fact that

it was performed all over Germany lead to a veritable land-slide

of artists willing to move on to the singspiel bandwagon. With

this as background Marco Polo have performed a great service in

giving us the opportunity to get to know this important piece.

But first the famous and heart-rending plot.

Alceste is married to Admetus who falls ill, near to death. The

opera opens at this point with a searching overture and moving

opening scene. Alcestis asks the Gods to spare him, but this is

agreed only on the grounds that someone else dies in his place.

No substitute can be found, not even his elderly parents, so Alceste

decides to offer herself despite the protestations of her sister

Parthenia. Hence the exacting and thrilling aria in Act 1 ‘Ihr

Götter de Holle (You gods of Hades). Alceste weakens so Admetus

is cured and returns from his bed to find his wife almost dead.

He learns of her sacrifice and immediately says that life without

her is no life at all. This leads to Alcestis’s death scene and

her moving aria ‘Weine nicht, du meines Herzens Abgott’ (Weep

not, idol of my heart). Admetus grieves, and a new character,

Hercules, descends and promises to bring back Alceste as her actions

and Admetus’ are honourable. Two glorious arias punctuate this

section: Parthenia’s ‘Er flucht dem Tagesleit’ in a gloriously

virtuoso style using the coloratura register and Hercules’ ‘Es

ist beschlossen’, his musical highpoint.

Needless to say all works out happily and the

music is at its most inspired in these final pages.

Of the two creators of this singspiel Wieland

was the most famous and probably the most important. Dr. Egon

Freitag in the notes tells us that he was "a novelist, translator,

publisher, editor and journalist" and produced "the

first important German translation of Shakespeare". Dr. Hele

Geyer in her essay on the singspiel itself tells us that Goethe

saw the piece and apparently left the performance "as one

would move away from an out of tune zither". Despite his

comments, its first performance on 28th May 1773 was

a success which "stimulated Wieland to establish a national

theatre (spoken and opera) as a model". She analyses the

music in some detail pointing out Schweitzer’s especially interesting

use of keys adding to the drama, and which helped to create what,

for the time, was " a very modern sense of realism",

with its "declamatory gestures and ‘furore’ types of aria".

In addition there is also a useful and detailed

essay by Reinhard Hasenfus on the full background and story of

Alceste as found in mythology. A synopsis of each scene is given

but the full text is available in German only. There are also

biographies of the performers.

Thinking of the performers and overall direction

of the work does however create a rather mixed reaction at least

from this writer. First the negatives.

Curiously the chorus have very little to do.

There is the temple scene in Act IV when they pray to the gods

for Alceste’s return and they briefly appear in the Finale. I

find them rather top heavy and recessed. The sopranos are too

full of vibrato. Alceste herself, Ursula Targler, seems mis-cast.

Surely she is really a mezzo in a soprano role. She seems to push

up at her high register to such an extent that it becomes quite

an irritant especially in the big florid arias. Christian Voigt

is too ponderous in the Bachian style seco-recitatives, and the

orchestra seems at times to be under-rehearsed.

Now some positives. Sylvia Koke is light and

airy as Parthenia but also full of pathos especially in the wonderful

moment in Act IV (Allmacht’ge Götter! Was seh ich?"

when Alceste returns to life and is reveal by Hercules. He is

ideally cast in the bass Christoph Johannes Wendel with just the

right amount of authority and weight.

The fact remains however that this two disc set

is probably only for those with a particular penchant for opera

of the classical period or in German theatre. Nevertheless it

is a fascinating document of a rather overlooked genre in a little

known category and at the very least gives us a clearer view of

where Mozart was coming from and how he added a greater dimension

to the genre.

Gary Higginson

Bill Kenny has also listened to this recording

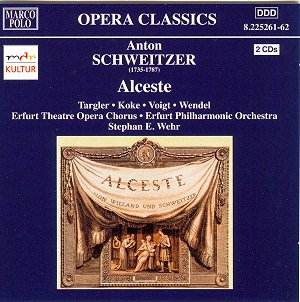

Naxos/Marco Polo are to be congratulated on the

release of this important rarity. Sometimes acknowledged as the

one composer who forged the link between the Baroque and Classical

periods in German music, Anton Schweitzer is also often credited

(jointly with the poet/librettist Christoph Martin Wieland with

whom he collaborated on Alceste) with the definition of

truly ‘German’ opera: at least in the Singspiel form adopted

by Mozart in Die Entführung and Die Zauberflöte

and later by Beethoven in Fidelio. This Schweitzer/Wieland

Alceste, first performed in 1772, was a huge success

in Weimar and beyond. It came to be much admired by Goethe who

nobly changed his mind about his first impressions of it once

he had met Wieland and grasped the true significance of the work.

This Alceste generated a whole new German national operatic

style, clearly different from the French and Italian styles that

prevailed formerly.

The detailed booklet essays on Wieland are by

Dr. Egon Freitag of the Goethe National Museum and on the opera

and its joint authors by Professor Dr. Helen Geyer. They offer

a wealth of information on the significance of the work and the

artistic statures of the composer and librettist. Professor Geyer’s

essay also discusses in detail the harmonic and structural innovations

that Schweitzer uses in the music. A synopsis of the plot, a scene

by scene account of the action and the German libretto are also

included.

The plot of the work is relatively simple: Alcestis,

wife of Admetus, a King of Thessaly who was formerly one of Jason’s

Argonauts, is allowed to replace her husband when he is about

to die. She makes this sacrifice willingly and though Admetus

lives on he is desolated by his loss. Since Admetus had no part

in influencing his wife’s decision and had valiantly attempted

to dissuade her from making it, the demi-god Hercules judges him

to have acted virtuously and returns Alcestis from Hades. This

version of the story (simpler than Lully’s 1674 version or Gluck’s

of 1767) requires only four principal characters and chorus.

The music is interesting rather than thrilling,

due in part to the limitations of the singers all of whom are

representative of a good provincial opera company rather than

a national one. There is a good deal of recitative, naturally

enough, but the work also has a number of appealing arias, pretty

duets and some agreeable chorus work.

In her essay, Professor Geyer rightly identifies

Alcestis’s aria "Ihr Götter der Hölle"

(CD1 track 4) for its dramatic significance and harmonic innovation.

However it is Parthenia, Alcestis’s sister, who has the highlight

of the whole piece in "O! der ist nicht vom Schicksal ganz

verlassen" (CD 2 track 7.) The orchestral sound is very good

and Stephan E. Wehr guides the work along with an assured hand.

It is clear that he cares deeply about this significant work and

that fact alone means that devotees of opera from this period

will not be disappointed by this landmark performance.

Bill Kenny