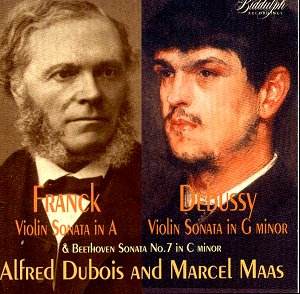

This is a disc even more impressive than Biddulph’s

collection of Bach recordings made

by these duo partners in the 1930s. If the Beethoven betrays some

idiosyncrasies it’s always engaging but the Dubois-Maas heartland

of the Franco-Belgian repertoire could not be more persuasively

explored than by these two embodiments of style and tonal nuance.

Dubois was born in 1898 and studied in Brussels. After leaving

the Conservatoire he moved in Ysaÿe’s orbit between the years

1917 and 1920, won prestigious competitions and teamed up in a

sonata duo with Marcel Maas. After his mentor’s death he was the

pre-eminent Belgian soloist, a position he was to hold for the

rest of his sadly curtailed life. A late 1930s tour of America

couldn’t be cemented because of the outbreak of war, during which

he formed a quartet and taught – his most famous pupil being Arthur

Grumiaux; both were superb Bach players – and he taught at the

Brussels Conservatoire for over twenty years. He died in 1949.

Maas’s career of course is more widely known – he lived on into

the age of the LP but his earlier recordings may come as a welcome

exploration of his youthful sonata playing.

The Beethoven Sonata, as I said, has its peculiarities.

It may seem somewhat brusque at moments but the compensations

are Maas’s beautiful clarity in the slow movement, the splendid

balance between the two, their ability to sustain slow tempi,

and Dubois’s classical lyricism and subtle bowing arm, those greater

gradations of colouristic potential that players of the Franco-Belgian

schools found. Dubois’s delightful little inflexions animate the

finale wonderfully well.

I have to admit that when it comes to listening

to the Franck I sometimes find myself wondering, not to put too

fine a point on it, where exactly I am in the work. Some performers

seem incapable or unwilling to distinguish paragraphs and movements;

the work becomes sectional, undifferentiated and uniform, a cyclical

exercise in static music making. Even fine musicians come badly

unstuck, as badly as they do for different reasons in the Mendelssohn

Violin Concerto. Music critics can shower superlatives like confetti

or denigrate with easy aplomb – but this really is a magnificent

performance. Dubois is neither smeary nor tensile; his portamenti

are acutely judged and employed without an obvious intermediate

note. Maas is reflective, his bass weighted sensitively. The sense

of musical and emotive deliberation is palpable, their shading

of colours and of volume in no way vitiated by a couple of little

violinistic intonational buckles toward the end of the first movement.

Dubois varies his intensity of phrasing in repeated passages,

adjusts his vibrato and together with Maas characterises each

movement with absolute authority. In a performance such as this

the sense of emotional engagement, expressive intimacy and of

musical inevitability are paramount. The tempo of the finale,

as elsewhere, seems just right, the elasticity and drama unfolded

with perfect judgement. Of all the performances I’ve heard of

this work – even Thibaud and Cortot’s, even Heifetz’s – none seems

to me to make more musical sense than this one, and few sound

so attractive and sympathetic.

The Debussy should be meat and drink to Dubois

and Maas and indeed it is. There is an idiomatic freshness in

the playing, a perfect accommodation of the sonata’s changeability

and malleability. Dubois is here the living embodiment of the

Franco-Belgian school; not as sensuous or evocative a tonalist

as Thibaud, of course – who could be – but one whose tonal limits

work entirely directly and with sure fidelity. One can listen

to him for example in the Intermède as his tone becomes

suggestively leaner, as his portamento elegance moves incalculably

from refinement to rhythmic coyness. Dubois and Maas are true

partners and their performance is a true classic of the gramophone.

Tully Potter reprises his notes to this issue

and he is rightly laudatory. I suggested in my notes to the Bach

disc that Dubois was a connoisseur’s violinist. Be a connoisseur

and admire his remarkable musicianship.

Jonathan Woolf