Weber is the living refutation of the idea that

German composers have to be serious-minded and logical. It is

true that he is always ready with an expressive turn of phrase,

amounting to real depth and poetry in slow movements, particularly

that of the Quintet, possibly the finest work here. But he is

also ready to break into cheeky humour – again the Quintet provides

the supreme example with its "Capriccio presto" Minuet

– and into virtuoso flights that exist purely for entertainment.

So much for Germanic seriousness, but he is no less of a free

spirit in his way of constructing a piece, always ready to dart

off at a tangent or to halt the proceedings because now it’s time

for some grand pathos or a dramatic gesture.

These particular works were inspired by the playing

of Heinrich Bärmann, whose triumphant first performance of

the Concertino in April 1811 led to the commission by the King

of Bavaria to write two concertos for Bärmann, both of which

were ready by July of the same year. The Quintet took a little

longer and is not to be considered a chamber work in the sense

of a piece for five equal partners, but a concerto for clarinet

with string quartet accompaniment. It loses nothing in the present

transcription and maybe gains something, especially when Faerber

is a snappier conductor than Blomstedt.

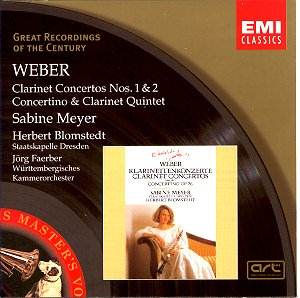

Sabine Meyer achieved notoriety following Herbert

von Karajan’s insistence on taking her into the Berlin Philharmonic

against the orchestra’s wishes (they felt she was a fine soloist

but not a good orchestral player). Her prowess as an orchestral

player is not on trial here; the important thing is that she proves

an ideal soloist, entering into Weber’s quicksilver changes of

mood, now poetic and musing, now sparkling and hugely virtuosic,

now powerfully dramatic. She has a wide range of tone and expression,

and total control over her instrument.

Due perhaps to the resonant Dresden acoustic,

Blomstedt does not always convince me that Weber’s imaginative

use of the solo wind instruments was equally matched by his command

of the full orchestra, which sometimes sounds muddy-textured and

unclear. But still, the reflectors are on Meyer and she never

lets go of you.

Christopher Howell

Great

Recordings of the Century