The critic’s hard heart can sink at yet another Tchaikovsky

in B flat minor. What can one say? From supercharged Horowitzian

glitter to the languorous narcissism of Pogorelich the catalogue

groans under the weight of entrants ranging from Tchaikovsky favourite

Sapellnikoff in 1926 to the latest octave-busting wunderkind.

If your tastes embrace, in addition to the above, say, Gilels,

Richter, Solomon, Rubinstein (with Barbirolli) or Argerich you

will be more than content and the prospect of another visitant

will not necessarily be overwhelmingly exciting – but then that

depends very much on the quality of the performance. And this

latest Concert Artist release is by a known and long admired exponent

of the literature, the ever remarkable, challenging and eloquent

Joyce Hatto. Her long series of recordings for this company has

once again launched her world-class technique and imagination

onto an ever-wider stage.

This is indeed a most perceptive and revealing

performance, one that fuses muscular control with acumen and insight

and in so doing opens up unexpected vistas in a work all too often

taken for granted. She has leonine strength – no doubt about it

– and a technique to match. With the strength comes clarity –

of passagework, yes, but also of intellectual and architectural

vision. Her rhythmic strength is undoubted as well. Listen to

her deliberate retardation of the solo line in the first movement

as she generates tension through the minutest of such gradations.

And here there are also moments where she perfectly integrates

the bravura with moments of intense, almost speculative reflection.

She explores an improvisatory quality in the first movement that

one does not ordinarily hear. At 11.40 the romantic tracery takes

on, in her hands, a bewitching aspect – one almost pointillist,

almost proto-impressionistic in its compression. At such moments

she seemingly takes the concerto beyond itself. In timing she

is equidistant between Richter and Pogorelich – but she generates

and sustains her own time here, unhindered by external temporal

considerations. Her Andantino is notable for a splendid sense

of her ensemble generosity. How verdant is the flautist here,

the orchestral playing being fiery and sometimes raw but extremely

exciting in general under René Köhler’s strong but

fluid direction. Hatto brings an aristocratic humour to her pointing

and in the Prestissimo section she is splendidly buoyant, avoiding

all sense of indiscriminate and generalized powerhouse playing.

Some may find her slow but many others will appreciate her finesse

and sensitivity. In the finale she once more generates tension

through shaping and not imposing it externally via less musical

means. So once more she is, for example, as in the slow movement,

half a minute slower than Solomon/Harty. There is a wealth of

detail here to savour from the moulding and inflections, the powerful

orchestral accelerandi, the finely chirping woodwind and the galvanizing

triumph of the final bars, which end a performance of constant

illumination and imaginative control.

Coupled with the Tchaikovsky is Saint-Saëns’

No. 4. She plays the Chaconne-like opening introduction with pensive

and withdrawn tone, chordally terraced with acumen, tonally splendid.

She doesn’t attempt to replicate Cortot’s more extreme rubati

(with Münch, 1935) though she doubtless discussed this concerto

with him in their work together after the War. Her right hand

runs are laced, quick, superfine, but unostentatious and no bar

to bringing out the melodic impress they bear. She and Köhler

are nowhere near as suave as, say, Entremont with the Philadelphia

and Ormandy but then I don’t think suavity is called for here.

By comparison with Hatto Entremont is hard, unyielding and just

plain lumpy. The wind and piano exchanges have a really delicious

affection to them and Hatto displays once more a characteristic

of hers in concertante works, which is to bind bravura and intimacy

so tightly that they become identifiable components of each other.

Hatto can be declamatory and bold but her tone never curdles or

hardens (it’s a characteristic of his, possibly exaggerated by

the CBS recording, that Entremont’s tone very definitely does

harden, and not just at climaxes). Her rolled chords are wonderfully

eloquent, her diminuendi full of poetry and her inwardness carries

with it mystery and depth. In the Allegro vivace she is delightfully

sprung and aerated - and serenity courses through the Andante

of the tripartite second movement before a driving concluding

Allegro. This, buoyed up by real tuneful elation, ends the work,

and the performance, in triumph.

This is a persuasively impressive coupling. Those

jaded by the Tchaikovsky may well want to sample Hatto’s Saint-Saëns

– but will, I’m sure, stay to admire her performance of the former,

which is as intelligent, sensitive and unselfconsciously authoritative

as the latter. Individual and strong, Hatto’s performances never

fail to inspire.

Jonathan Woolf

MusicWeb

can offer the complete

Concert Artist catalogue

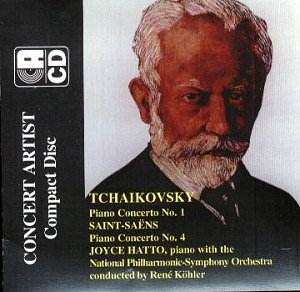

![]() Joyce Hatto (piano)

Joyce Hatto (piano) ![]() CONCERT ARTIST/FIDELIO

RECORDINGS CACD 9086-2 [61.47]

CONCERT ARTIST/FIDELIO

RECORDINGS CACD 9086-2 [61.47]