When a great composer dies leaving a final work unfinished,

sometimes the work is completed by his students or friends and enters

the repertoire with barely a ripple of comment. Bartók’s Viola

Concerto, Borodin’s Prince Igor, Tchaikovsky’s Third Piano Concerto

and Prokofiev’s cello sonata are examples. Sometimes the work remains

uncompleted and the subject of years of discussion, even controversy,

before, eventually, someone is able to produce a satisfactory completion.

Bach’s Kunst der Fuge, Mahler’s Tenth Symphony, Berg’s Lulu,

and Elgar’s Third Symphony come to mind. In some cases the work is published

complete and only many years later are questions raised. In this latter

category lie Offenbach’s Les Contes d’Hoffmann and the Mozart

Requiem.

At the time of his death, Mozart had written out the

vocal parts and accompanying bass part of 10 of the work’s 14 sections

and the first 8 bars of the Lacrymosa. The familiar version of

this magnificent work was produced for Constanze Mozart by three of

Mozart’s students—Freystätdler, Eybler, and Süssmayer—and

delivered in satisfaction of the commission with a forged signature

on the colluded manuscript. Besides filling out the orchestration of

the entire work, Süssmayer is credited with composing anew the

Sanctus, Benedictus, Agnus Dei, Osanna and

Lux Æterna. It was actually 1823 before serious questions

were raised as to just how much Mozart may have had had to do with it.

The fundamental problem is that this is exceptional

music and Süssmayer was an uninspired and unskilled composer, so

how much of his contribution to this work is based on Mozart’s lost

sketches or verbal instructions? Levin argues that quite a bit of it

is authentic Mozart, clumsily worked out by Süssmayer. Levin carefully

works around the bits of what he sees as authentic Mozart and patches

up Süssmayer’s inept extensions. The result is certainly the finest

version of the work I’ve ever heard, and since it was premiered in a

1991 recording by Helmuth Rilling it has also been recorded by Martin

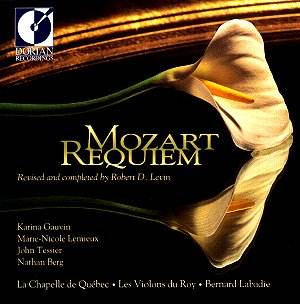

Pearlman and now Bernard Labadie.

Throughout, the orchestral accompaniment is lighter

and more supple, which allows a smaller chorus to be more forward. The

additional fugues composed by Levin are beautifully done, perhaps with

just the merest echo of the Mozart c-minor mass and the Bach b-minor

mass. The "repairs" of Süssmayer’s work are seamless

and have the effect of making the work feel more consistent and more

fluent. I have sung the Süssmayer version and expected to feel

the changes in my throat, but everything came off perfectly comfortably,

and my wonderful memories of working on this music are intact. The occasionally

recorded Maunder revision leaves out several major sections of the music,

but Levin includes all the familiar music and also composes an Amen

fugue (based on Mozart’s sketch) after the Lacrymosa so you get

your full money’s worth here. Levin’s revised Hosanna fugue is

in a single key and shortened in the reprise after the Benedictus

(in the customary style of 18th century church music),

and will be the other change noticeable to most listeners.

When I was in Montreal in 1997 I was privileged to

attend a marvellous performance of Rossini’s opera La Cenerentola

and my recollection is that many of these fine Canadian musical artists

were part of that performance, so I am not surprised at the excellence

of their work on this recording. Nor am I surprised that their approach

is operatic and dramatic. La Chapelle de Québec is a fully professional

choir and their precision and dramatic declamation in the denser choral

parts is truly thrilling. This is advertised as a live recording, but

there is no trace of audience sound except some discreet applause after

the end. Of the many performances of this work I’ve heard and cherished,

beginning with the Scherchen 1953 monophonic Ducretet-Thomson and including

the Harnoncourt, Hogwood, and Solti Vienna video versions, this recording

will now be my first choice.

However, with a work recorded as frequently as this,

a person can pick and choose until just the perfect version is discovered.

Some will prefer every note of the Süssmayer version out of familiarity,

and some will prefer a more solemn, weighty, reverent, even sentimental,

approach.

Paul Shoemaker