AVAILABILITY

http://www.chitoseokashiro.com/chateau_e.html

Cathedral Station, P.O. Box 1869, New York, NY10025

infoChateau@aol.com

Interview with Okashiro: http://members.aol.com/okashirore/

Letís start with a question: other than to maintain

ourselves in a state of robust impecunity, why do we buy CDs?

The answers, roughly speaking, are gratification, education, and

elevation. CDs, or any other recorded music format you care to

mention, provide service on tap for our physical, mental and spiritual

needs though not necessarily all at once, or even in that order.

Itís not very often - Iíd even go so far as to say itís very rare

- that a CD comes along which steps outside these normal parameters

and challenges our conceptions of the very fabric of this thing

we call "music". This issue looks like one of that rare

breed.

"Oh, come on," I can hear you

saying, "Whatís the Big Deal? Itís only a piano transcription!"

It would be a fair comment, so letís muse on it for a while. As

long as weíve had music, weíve had folk who arrange music conceived

in terms of one instrument or ensemble for some other instrument

or ensemble. In the beginning, as I imagine it, because the truth

of the matter is shrouded in the mists of time, it was "Hobsonís

Choice": either arrange music for the instruments to hand,

or donít play it at all. By and large, up to the Nineteenth century,

"expediency" was the watch-word.

Then other factors entered the fray. With the

advent of the instrumental "virtuoso", arrangements

became rather handy vehicles for showing off oneís digital dexterity.

I get the impression that "artistry" generally took

something of a back seat. At the more mundane level, arrangements

of "large" works, particularly for the increasingly

ubiquitous piano, provided the "pre-gramophonic" public

often with their only avenue for experiencing such works at all.

I donít know about you, but thinking about that gives me

the colly-wobbles! Somewhere in between came the exponents of

instruments not over-endowed with available repertoire. I suppose

we could call these the "neo-expedients".

Of course, it wasnít all "down-sizing".

Some composers, seeing the potential for the "up-sizing"

of, say, solo piano works, busied themselves with orchestral arrangements.

However, all arrangements have in common one thing, which is true

whether at one extreme you set out to simply reflect the original

as faithfully as possible, to make what might be properly termed

a "transcription" or, at the other, you set out to completely

re-think the piece from the ground up. This common factor is that

if you "arrange" a piece of music it becomes, to a lesser

or greater extent, a different piece of music, which must

be judged on its own merits.

That sounds a bit obvious, doesnít it? Obvious

or not, arrangements are real opinion-polarisers. Some folk I

know say they "donít like" arrangements, largely because

they "donít see the point" of messing about with a "perfectly

good piece of music". Their problem, if "problem"

it be, is that they canít see the arrangement as "different"

in any essential way. Others, myself included, are fascinated

by arrangements, largely because they want to find out what is

the point of messing about with a perfectly good piece of music.

With a bit of luck, you end up with two perfectly good pieces

of music for the price of one!

In which of these pigeon-holes does the work

on this CD fit. Nowadays, when the CD catalogueís cup runneth

over, I think we can safely discount it being for the express

purpose of accessibility. With greater confidence, I will declare

that this issue has nothing to do with neo-expediency. With a

recklessness bordering on abandon, Iíd kick out the idea that

this is the plain "transcription" it claims to be -

transcriptions of even relatively "straightforward"

symphonic works struggle to convince, so on that score this has

no chance! That leaves us with "re-thinking from the ground

up" and "virtuoso show-off piece". If at this point

I let it slip that the arrangement follows the line of the original

practically bar for bar, and bearing in mind that itís Mahlerís

First Symphony weíre talking about, youíd get maybe just

a sneaking suspicion that this is a "show-off", wouldnít

you?

Ha! This is where it gets tricky! The booklet

note, juxtaposing a 1Ĺ page article "Titan at the

Keyboard" by "jd hixson" with a transcript of an

interview with the arranger and performer Chitose Okashiro, suggests

that the purpose is none of the aforementioned. This is central

to the issue, so Iíd better try to give you the gist of it. Mahlerís

music opened new dimensions whose "reverberations can be

felt yet to this day". Does this imply that a contemporary

transcription would be nothing more than an act of virtuosic vanity?

Does not the current stranglehold of the "authentic performance

movement" in any event render such a whim "unthinkable"?

It is suggested that Mahlerís own excursions into the arranging

of other composersí music proves that an arrangement is justified

in "the context of its creative achievement". I say

this ignoring any nit-picking observations to the effect that

such a statement will always be true! As far as the piano

is concerned, the arrangerís art "summons new levels of virtuosity

through which to project dimensions and textures envisioned for

the orchestra".

You might be forgiven for thinking that this

is just an excuse for some megalomaniac pianistic posturing in

the grand old manner of Franz Liszt at his most showman-like -

but hang on, thereís more. The author reflects on the culture-shock

of modern recording, which has perhaps caused instrumentalists

to become paranoid about technical perfection. In something of

a non sequitur, she concludes that the art of transcription

demands closer interaction with the original score, suggesting

that in the "juncture of composer/performer/listener"

(shades of Arnoldís musical philosophy!) the transcriptive art

"dwells most deeply". And so on. In other words, by

peeling off some of the wrappings we might see more of whatís

inside the package. Now, thereís a revelation!

Okashiro, to my intense relief, declares that

"playing transcriptions does not mean to imitate the orchestra

sound at all". That would be a real waste of time, with real

orchestras the world over churning out "Mahler Firsts"

like Model T Fords! She thinks that pianists these days have,

to some extent, buried their heads in the bellies of their instruments.

She finds that sticking her head above the pianoís parapet and

actually taking notice of the sound of the orchestra provokes

ideas on how to expand her own pianistic potential, whilst the

hard-bitten pianist in her canít help winkling out elements in

symphonic works that her instrument might be able to express rather

more effectively. Thatís an interesting idea - transcribing from

orchestra to piano in order to improve the impact of the

musicís message! Nevertheless, Okashiroís "bottom line"

also conforms to the "wrappings removal" model. She

believes, as happens for example in the piano duet version of

Le Sacre du Printemps, that stripping off the luxuriant

upholstery of the orchestration exposes the harmonic nerves, the

melodic guts, and the rhythmic skeleton of the music - my imagery!

Bruno Walterís four-hands transcription was,

it seems, conceived specifically for domestic consumption in an

age when performances and recordings were pretty thin on the ground

- the "accessibility" model. Consequently, it tried

to convey an "accurate" impression of the original score,

right down to 56 bars of a tremolando "A" to simulate

the mysterious string sound of the opening. His intentions were

of the very best, but as far as Okashiro is concerned such mimicry

is artistically arid; if she is to convey anything meaningful

she perforce must follow the "re-thinking from the ground

up" model.

This is perhaps just as well. The very idea -

of one pair of hands getting to grips with every note of

a symphony that can stretch the capabilities of a hundred - would

set new standards of utter implausibility. Speaking strictly for

myself, I feel that the entire undertaking sounds implausible

enough as it is; a far more ambitious venture than Mussorgskyís

transcription of Ravelís Pictures at an Exhibition - says

he, tongue firmly in cheek! The question is: in terms of both

her arrangement and her performance, does she succeed? And, while

weíre at it, do we really discover anything about the music that

we didnít know already? Alright, thatís two questions, but whoís

counting?

Before we dive into the music, letís look briefly

at the "ancillaries". This is the first recording released

on this label, which is Chitose Okashiroís own venture. At first

glance, there seem to be no details about the recording or its

participants. Itís only when you remove the CD that you see the

information, full details right down to the name of the piano

tuner (who must have been kept busy!) tucked away on the inside

of the u-card behind the transparent CD tray. "JD Hixson"

turns out to be the recording producer who, with engineer Tom

Lazarens and editor Marc Stedman, has done a cracking job of capturing

the formidable sound of the Hamburg Steinway piano that is on

occasions tested almost to destruction. The recording is rich,

wide-ranging, quite closely-miked but with a satisfying ambience.

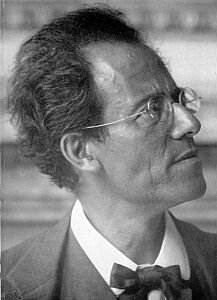

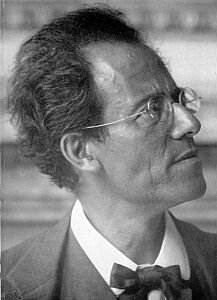

Oh, and I couldnít help noticing the similarity of pose between

the cover picture of Okashiro sporting a possibly inapt "halo"

and a famous photograph of Mahler himself (above

left). Go on, somebody tell me it was entirely coincidental.

I mentioned the "skeleton of the music"

a few paragraphs back, and that fits the very opening like a glove.

Oddly, the fourths at the start sound a bit "harpsichordish".

Can anyone tell me how this is done? With the spread of As

supplanted by long, decaying bass notes, Mahlerís chains of descending

fourths emerge from almost total darkness, like splinters of bone

penetrating black velvet. Shorn of its luminous sheen, this sounds

less like nature stirring in the mists of dawn, and like something

much more protean - an impression that grows as the long introduction

proceeds and is reinforced during the gloom of the development

section. It feels like we have uncovered the moment of conception

of the Third Symphonyís vision of raw life emerging from

primeval ooze.

The main subject is beguilingly played, but culminates

in a startlingly ferocious climax. Yet, reflecting as you listen,

you realise that this ferocity is actually inherent in the original.

Again, as the main subject resurges, the "out for a walk

in the country" feeling is countered by emergent violence

in the harmony: we may be out in the countryside, but by gum itís

a dangerous place to be! At the point where Mahlerís structure

seems about to rip itself to shreds, you might reasonably expect

a pianist to keep the tempo moving to prevent tension-sapping

gaps appearing between the notes. Okashiro does the opposite!

She sustains the crackling tension through such sheer brute force

that I had to look again at the sleeve picture: surely that slip

of a lass couldnít clobber a keyboard with such colossal weight?

It was almost a relief that, at the end of the explosion of fanfares,

the continuity momentarily faltered! Only momentarily, mind. She

blazes into the finishing straight with a bruising belligerence,

an image of beastly nature on the rampage that confirms both that

parallel with the Third Symphony and the impression that

she is a pianist of phenomenal talent.

After all that frenetic activity, I was ready

for a breather! The second movement sets off with commendably

rude and robust good humour but, as the theme repeats, so it gets

progressively more aggressive. However, in the main subjectís

"development" the weird dissonance of Mahlerís original,

which you might expect to be even more acidic on the piano, emerges

simply as less diffuse, articulated with the refreshing impact

of splashing spring water, albeit with a thunderous left hand

contributing to the climax! The subsequent, subdued reprise of

the tune is delightfully pecked out, a naive hesitancy that soon

bubbles into a surge of sheer joy. Okashiro invests the central

waltz with a fetching Viennese lilt, stepping and swaying languorously

as if to the manner born - this is thoroughly enchanting. The

close of the movement is by now almost a foregone conclusion,

except that the former aggression has somehow mutated into boisterous

bravado, one presumes under the influence of some schnapps sipped

during the central waltz!

In the third movement the funereal round on Bruder

Martin sets off conventionally, I suppose largely because

thereís not much else you can do with it, but at least it afforded

me the few moments of repose Iíd been gasping for at the end of

the first movement. Overlaying the gloom with some artfully varied

attack, Okashiro makes the high-stepping counterpoint prick the

mournful monotony almost like a sudden squirt of juice from a

lemon and straight in the eye, at that. This is a minor galvanic

jolt that stimulates awareness of the shifting colours she is

squeezing from the slowly revolving, intertwining lines of the

dirge. In the contrasting, wickedly witty "knees-up"

she proves the very model of bad taste, having no truck with the

percussive pussy-footing that bedevils most orchestral performances.

Instead, there are lashings of rumbustious rubato and hair-raising

hairpins that should bring tears of mirth to the eyes of even

the most hardened Mahler purists. In the subsequent wind-down

towards the centre of the movement she exposes some gut-squirming

dissonances, although the tender "lindenbaum" episode

itself brings no surprises except that, in spite of being played

with tenderness and delicacy, it sounds a bit penny-plain. The

reprise of the dirge, booming through the belly of the piano,

is looming, ominous, purposeful, a powerful accumulation of the

elements of the movement that engenders a savage jubilation in

the returning "knees-up" music. This is as near as Iíve

ever heard to "the animals of the forest dancing on the hunterís

grave".

Do you find that, in the hands of a top-flight

orchestra and conductor, Mahlerís stürmisch bewegt

engulfs you in torrents of terrifying torment? If so, then prepare

yourself for a real shock. As youíd by now expect, I can tell

you that Okashiro does indeed turn the wick right up for the start

of the finale. However she finds something that to the best of

my knowledge no conductor has found nor, I suspect, would dare

to find: bedlam! Rarely, if ever, has that "heart"

been so "sorely wounded". Of all the passages that have

given me pause for thought, this one, more than any, vindicates

Okashiroís claim that there are some things that the "target

instrument" of an arrangement can, in some way, do "better"

than the original scoring. There, Iíve said it. Now I await the

wrath of Stravinskyís "inevitable German professor"!

Pretty well all the notes you hear are recognisably from Mahlerís

hand, and I get the feeling that Okashiroís arrangement has somehow

- and incredibly - hung on to most of them! In so doing, she has

set herself a very considerable virtuosic challenge, which by

the sound of it has brought her right up against the stops of

her present capabilities. My guess is that the sheer block-busting

effort involved, allied to the nature of the piano, is what produces

this palpable sense of tempestuous chaos. Whatís more, thereís

no sense of Lisztian showmanship here, just red-raw, blood-curdling

musicianship.

In the aftermath, Okashiroís fingers capture

a real feeling of straining in the upward-striving lines, and

her view of the second subject is anything but serene: "wracked

with anguish" would be nearer the mark. Itís not so much

a contrast with as a continuation of the first subject, lending

a new edge of meaning to the rumbling return of the first movement

material that bridges to the subsequent climactic outburst. Her

delicacy of touch in the moment of fanfare-laden quiet is as exquisite

as her attack in the build-up to the "false dawn" is

ferocious. Likewise, the parade of past themes passes in a panoply

of filigree, and the coda storms the barn in no uncertain manner.

It is only in the tearaway closing bars that you get a feeling

that sheís running out of steam. Do you know something? I think

that this might well be entirely deliberate.

This is not pretty music, but it is pretty impressive,

not least in the sheer audacity of the undertaking, which sounds

like something that should not even be attempted by any pianist

who canít eat Lisztís arrangement of Beethovenís Ninth

for breakfast along with a minimum of three Shredded Wheats. Chitose

Okashiro is a formidable pianist: I have this nagging suspicion

that her hobbies must be something like miniature flower arrangement

and smashing piles of roof tiles with her bare hands.

Iíll admit that I had fully expected this CD

to enshrine a fiasco, thinking something on the lines of, "Mahlerís

First on a piano? Donít be so ridiculous!" To my utter

astonishment, I was completely bowled over by it. Now, I am fully

aware that my judgement may have been clouded. At my time of life

"astonishment" is an increasingly rare experience, so

Iím more than content to be astonished. Nevertheless I have tried

to make allowances for this happy state of affairs. There are

imperfections, hardly surprising, and just very occasionally I

was tempted to think that there are maybe one or two places where

the "drum-roll" left hand and sustaining pedal are laid

on a bit thickly. Yet, all these pale into insignificance when

set against the revelatory nature of the "transcription"

and the authority which Okashiro brings to her performance. Sure,

I can imagine it being done better, but only by stretching my

imagination a little - about as far as Okashiro has stretched

her technique!

As Mr. Spock might have said, "This is Mahlerís

First, Jim, but not Mahlerís First as we know it."

The lady is right, it does indeed make you think again, and think

carefully about what the music is "about". Moreover,

the revelations are not limited to the substance of the arrangement,

but often emerge from the style of the interpretation. Iím thinking

particularly about her highly elastic phrasing, a required characteristic

of Mahlerís music that is so rarely given enough air to breathe

or worse inappropriately applied by many conductors. Chitose Okashiroís

arrangement - and her breathtaking performance - make you realise,

in contradistinction to his long-held reputation as a bit of a

"wild child", just how refined a composer was

Gustav Mahler. It seems to me that both my questions have been

answered in the affirmative.

Paul Serotsky