I first encountered Joby Talbot, albeit without knowing

it at the time, when switching on the television late one evening I

happened to catch a live performance by Neil Hannon and his "pop"

group, The Divine Comedy. I can recall being fascinated by their

ambitious instrumental arrangements and memorably melodic yet often

adventurous song writing - a kind of "prog-rock" group for

the 1990s. I immediately rushed out and bought the album they had been

promoting in the television show, fin de siècle, a disc

that has remained a firm favourite ever since. Only later, when I came

to know Talbot’s name through classical circles did I realise that his

writing and arrangements were an integral part of The Divine Comedy

sound.

Talbot first collaborated with Neil Hannon in 1993

at around the time he was completing his college studies, a formal and

conventional musical education that had seen him study with Brian Elias,

Simon Bainbridge and Robert Saxton. His credentials were displayed early

and the 1990s, whilst Talbot was still in his twenties, saw works for

the BBC Philharmonic, Britten Sinfonia, Brunel Ensemble and Crouch End

Festival Chorus amongst others. Yet one senses that although these pieces

were written alongside Talbot’s work with The Divine Comedy,

they co-exist entirely naturally, the work of a composer whose integrity

and faithfulness to his own musical instincts is at once apparent.

Stylistically the music on this disc is perhaps somewhere

between Michael Nyman and Philip Glass although Talbot clearly fights

against any overtly dominating influence. Indeed, Talbot and The

Divine Comedy have collaborated with Michael Nyman during the 1997

Flux Festival, a fruitful partnership that won them considerable acclaim.

The two String Quartets of 1998 and 2002 respectively, and in

particular the second, clearly owe something to Glass in their shifting

rhythmic and harmonic patterns although Talbot allows himself a greater

degree of overall license and flexibility whilst still laying the inner

workings of the music bare and clearly open to scrutiny. In contrast,

Blue cell, commissioned by and played here superbly by the Apollo

Saxophone Quartet, is the opposite of what we would conventionally expect

of a work for this ensemble, a study in twilight, hauntingly atmospheric

in its shaded, fluttering textures and delicately hued colours, reflecting

a side of the ensemble not commonly exploited and all the more effective

for it.

That Talbot is not afraid to wear his heart on his

sleeve is a recurring factor in these works and comes to the surface

particularly in the brief but touching solo piano piece, 6/11/98,

the date of Talbot’s wedding to artist Claire Burbridge and "…similarities

between diverse things…" a moving threnody in tribute to Fred

Hutchins Hodder, a twenty year old violinist and mathematician who died

tragically between Christmas and New Year 2001 whilst a student at Pembroke

College, Cambridge.

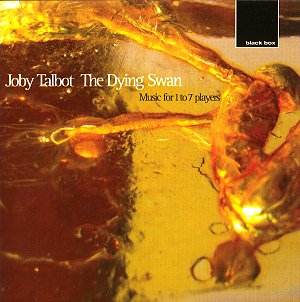

The Dying Swan stands apart from the other works

on the disc both in terms of its length, a three movement suite extending

to around thirty five minutes, and also in its conception as a score

to accompany the 1916 silent film of the same name by the Russian Yevgeny

Bauer, the music originating as a commission from the British Film Institute.

Talbot weaves music of real beauty here, often with the simplest of

material that he develops with a transparent and logical ingenuity,

yet the underlying pathos and ultimate tragedy of the film is certainly

not lost in the more dramatic moments of the music. Most striking of

all perhaps, the suite commanded my attention for its entire span, an

accolade that certainly cannot be applied to every contemporary score

of this scale I hear these days.

Without exception the performances of all of these

works are exemplary. I have already singled out the Apollo Saxophone

Quartet but the contribution of The Duke Quartet is also of the highest

quality, the recorded sound rich with a resonance (presumably studio

aided) that is, nevertheless, perfect for the textures of these particular

chamber ensembles.

If I had to name a young composer who summed up the

post modernist musical ethic then it would be Joby Talbot. Versatile,

emotionally transparent, thought provoking and above all enjoyable and

accessible without personal or artistic compromise. What emerges is

a musical renaissance man, a genuine voice for the new millennium in

its dawning years.

Christopher Thomas