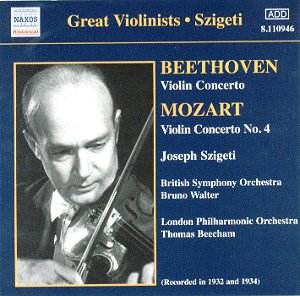

Two of Szigeti’s greatest concerto recordings were

recorded in London between 1932 and 1934, when he was at something like

his prime, and are conveniently harnessed in this super-budget Naxos

‘Great Violinist’ release. The Mozart is one of three recordings made

with the LPO and Beecham – the others were the Mendelssohn and Prokofiev

1 – and the conductor’s contribution to this Mozart performance is characterized

by note writer Tully Potter as "brusque … and slapdash." Presumably

therefore Szigeti’s marvellous performance worked in spite of, not because

of, the conductor – not an argument I would be prepared to follow too

far. In fact Beecham’s accompaniment is perfectly acceptable and animates

Szigeti’s sometimes miraculous playing to a large degree. The violinist

is stylish and aristocratic in equal measure, utilising the Joachim

cadenzas, reaching a peak in the slow movement, a benchmark performance

by which I judge all other recordings. He vests the lyric phrases with

a chaste intensity seldom experienced in Mozartian concerto performances.

The contrastive material is charmingly intensified by Szigeti, rather

than being allowed to dissipate, Beecham encouraging orchestral pizzicati

that are properly energetic and characterful. Throughout the conductor

offers warm and generous support. Szigeti’s elastic phraseology comes

to the fore in the Rondo finale, panache and elegance co-existing in

perfect accord. Of the musicians of Szigeti’s generation probably only

Thibaud was as elegant and convincing a Mozartian and when the Frenchman

was finally taped in the D major, off-air in 1951 with Enescu conducting,

his technique had long since withered leaving behind just the wonderful

instinct for phrasing.

Szigeti recorded the Beethoven Concerto three times,

twice with Bruno Walter conducting. The 1932 Walter recording was followed

by a New York Philharmonic one in 1946, the trio being completed by

the Dorati accompanied LSO recording of 1961, by which time the violinist

had been in long and steady decline (horror stories of the violinist’s

frailties have emanated from the LSO Dorati/Menges sessions of 1959/61).

The 1932 performance is a thoroughly impressive one though not without

its idiosyncrasies. One of the most obvious is Walter’s highly subjective

handling of the orchestral introduction, his frequent intemperate accelerandos

invariably accompanied by an increase in orchestral volume, none of

which ideally prepares for the violinist’s broken octaves entry. There

is also some booming bass in the acoustic of Central Hall, Westminster,

which can occasionally serve to cloud and occlude the lower string line.

But it is to Szigeti that we must turn to appreciate the true stature

of the reading – his portamenti are expressive, his line fuses animation

with relaxation, whilst conveying all the while a sense of involving

depth. In the Larghetto, moments of pregnant expressive meaning are

infused with subtly increased vibrato usage and colour, his portamenti

beautifully apt and clear, those "backward" portamenti for

which he was (in)famous always constructively employed. His correlation

of individual episodes here is of the highest architectural acuity and

his playing of singular beauty, even if tonally he lacks precisely that

quality; at moments such as this it’s of little account. His Rondo finale

is full of fresh air, with some deliciously quick and easeful slides

accompanying him, and a sense of conclusive surety and delight in the

playing.

The transfers have been well handled by Mark Obert-Thorn.

As for the performances – well these are indispensable cornerstones

of a collection, and not just a historical collection.

Jonathan Woolf