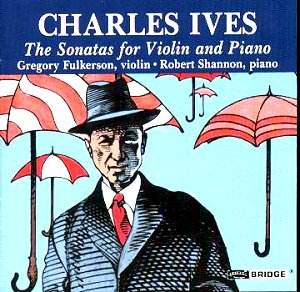

Dating from between the years 1902-15 these four violin

sonatas are amongst the greatest of all Ives’ chamber works and present

the Ivesian aesthetic in all its radical and manifold complexity. The

juxtaposition of hymn tunes and the technical means open to him to explore

such material – clusters, polychords etc – give the sonatas a fruitful

tension, technical and expressive, that vests them with intense, frequently

speculative depth.

The intriguing canonic implications of the piano writing

in the first movement of the First Sonata serve notice of Ives’

seriousness; this movement is strong-willed, with violin light and piano

severe, quilted quotations stitched into the score and a magical return

to the opening theme. The violin enters the Largo cantabile second

movement muted, but the piano drives from piano to a strong forte, scraps

of tunes shed throughout – The Old Oaken Bucket, Tramp Tramp,

Tramp – whereupon the violin’s reminiscences are violently attacked

by the raging, torrential piano clusters for a brief moment before the

violin muses on. The final movement, a longish Allegro, opens with the

piano in rather martial fashion and the violin correspondingly pliant;

the violin becomes increasingly lyrical, with a sense of syncopation

never far away and rhythmic displacements ever possible. The close of

the work is one of elegiac serenity, with an extreme diminuendo from

Fulkerson – highly effective – and beautifully simple, spaced chords

from Shannon’s piano. The Second Sonata had an even slightly

longer gestation period, dating from 1902-09. The opening movement,

Autumn, veers between tempo extremes with melodies of optimum

elasticity, and a battle of wits is immediately set up between instruments.

After an abrupt start the second movement, In The Barn, soon

becomes drenched in barnyard Americana, sailors’ hornpipes and syncopated

tomfoolery, country fiddle playing. Here Fulkerson is adept at hardening

his tone – and with no sign of fakery; nothing would destroy the characterisation

more quickly here than some arch fiddling. In fact both men relish the

teasing accents and rhythms here and elsewhere. The final movement,

a set of variations, is extremely quiet and intense, gathering in spiritual

depth before expanding in tempo and dynamics and overt lyricism. The

hymn tunes become fervently rapturous, the piano’s heady dynamism and

violin’s hypnotic exhortations embodying powerful truths before slowly

winding down in noble simplicity.

The Third of the quartet of sonatas was written

and revised between the years 1905-14. There is an alternating sense

of strength and lyric ardour in the opening movement, the piano adding

a dissonance and flair under the violin’s ever-arching lyricism. Some

ingenuous interludes for the piano act as musical buffers, as earlier

themes are revisited by both instruments. There’s tremendous drive to

the Allegro with the brio intensified by Fulkerson’s deliciously

quick portamanti – entirely apt as well. This is by some way the longest

of the sonatas, lasting a good half an hour; the weight falls in the

two outer movements. The listless, rather fragmentary start to the Adagio

cantabile final movement hints at darker directions – but little

moments of aspirational simplicity manage occasionally to emerge and

slowly the hymn tune unravels with a clarifying and cleansing beauty

that seems to beatify all the struggle that has preceded it. Szigeti

once recorded the Fourth Sonata, Children’s Day at the Camp

Meeting. Its programmatic generosity is always delightful and never

more so than here. There is something passionately aloof about the writing

in the second movement – the work lasts barely eleven minutes – and

also some wild clustered piano, boisterous and child-wild – leading

onto some simpler material including, most unusually in these works,

a little pizzicato episode. The final statement of the hymn theme emerges

with all Ives’ reverential nostalgia. His ingenious vitality is given

full rein as the work finishes, quirkiness and affection coalescing

into simplicity, even with the question mark at the very end.

There is only one problem with this Bridge release.

Unfortunately the recording has spilled over to a second CD – the two

last 79.52 in total. Competition comes in the form of Hans Heinz Schneeberger

and Daniel Cholette on ECM and they are on one 76 minute CD. Bridge

is still offering this Fulkerson-Shannon traversal at full price [around

£22], which makes it ungenerous in the extreme. I would urge them

seriously to reconsider and to issue this as a specially priced single

(which is effectively what it is). Fulkerson and Shannon’s superbly

idiomatic performances surely deserve no less.

Jonathan Woolf