A Brief Introduction to the Life and Work of Sir Granville Bantock by Vincent BuddThis is a much-needed corrected and revised version of the essay hurriedly put together a couple of years ago for this site. It also now includes a few photos some of which have kindly been supplied by Anton Bantock, GB's grandson, from his recently collated set of prints. ©Vincent Budd 1997 2000 see new booklet This is a long article (15 A4 sides) Introduction Background Royal Academy of Music New Quarterly Musical Review  The Gaiety Company New Brighton Birmingham and Midland Institute Peyton Professor A Birmingham Orchestra The Lure of the East Literature and Classical Antiquity The Hebrides Competitive Festivals Recognition and Indifference Trinity College Final Years Epilogue

Sir Granville Bantock probably has the unenviable distinction - with less than a handful of other arguable challengers - of being the most unreasonably neglected composer in the whole pitiable chronicle of neglected 20th century British music. He is truly the supreme musical Ichabod of our Isles and the almost complete disappearance of his works from the repertoire of his country is one of the strangest and perhaps saddest musical biographies of recent times. The winds of cultural opinatry and the gravities of critical mythologising have condemned him to a limbo of fabled ingloriousness and he is left as nothing much more than a fleeting footnote in the histories of British music: his foibles and idiosyncrasies have been exaggerated and his gifts minimised, misjudged, and precondemned; characteristic idioms glibly recast into mannerisms, influences reduced to imitation, and critical marginalisation all too easily transfigured into musical fault in the shallow doctrines of accepted musical historiography. Yet, for all the unfounded, beggarly, and ignominious inscriptions cast upon his name down the years, as our century passes into another the music of Granville Bantock, like that of Herbert Howells, could well be on its way to becoming another prized rediscovery from our wasted musical treasures. A man of remarkable musical gifts, of unquenching, and sometimes wayward, enthusiasm and energy, of full-blooded humanity, of lavish generosity, and of great charm and many friendships, and whose heart seems to have been as large as his imagination, he was not simply an important figure in the so-called renaissance of the country's music, but also without doubt one of the finest and most remarkable British composers of this century, his work at its best once heard not easily forgotten. Despite the few works with which his name is often associated, he was a prolific composer and left behind an enormous body of music, sometimes writing on a grand and ambitious scale, invariably expressly and colourfully programmatic, but with an accompanying masterly understanding of orchestral effect. He was indeed quite capable of pastiche and his work could possess the lustre of the musical veneer; he sometimes wore his influences far too easily on his long sleeves; he could be extravagant and trifling, and occasionally display the worst faults of Edwardian indulgence. Indeed, the intemperance of his muse could (especially in the early days of his career) out-will a certain musical maturity - more was at times much less. Yet amongst his vast oeuvre are some of the noblest and individual creations of the last hundred years. Such was the scale of his musical intent and the breadth of his inspiration, his music when occasioned, as in some of his piano arrangements for example, simply reveals the everyday embellishment of his skill, mere divertissement, and the more immediately practical and professional musicality of the commercial commission - unlike a number of other more monied composers, GB depended on his music for a living. However, at its finest, his work undoubtedly possesses the obvious mark of greatness and can stand proud alongside any of the achievements of more illustrious and lauded figures of 20th century British music. If his compositional gifts seem at times to have come with an unrestrained and indiscriminate and adaptable facility, he nonetheless composed some of the most sublimely elevating and perfectly created musical legacies which any nation could wish to possess and which in most other countries would be a well-worn but still well-greeted feature of its orchestral repertoire - and featured on every 'British Greatest Hits' from here 'til Kingdom Come. His friend Elgar, once described him 'as having the most fertile imaginative brain of our time': in fact at the height of his fame, in the first decades of this century, Bantock rivalled his friend as the premier musical figure in the country and why this is no longer the case is just as much a question of the whims of cultural fashion and the promiscuity of human reason as the possible adverse quality of his music. In his short musical autobiography Vaughan Williams noted his regret in not having become his pupil, as Elgar had suggested, since 'what Bantock did not know about the orchestra is not worth knowing'. GB's advocacy though is not dependent upon a reputation-by-association or indeed some judiciously worded apologia: the enduring and commanding glory of some of his music stands by itself majestic, mighty, and magnificent for all to hear. In short, his neglect is unwarranted. If the recent 50th anniversary of his death was met with only a minimal recognition in the hegemonic echelons of our musical polity, then the recent set of CD recordings, particularly on the Hyperion label, has once again laid before us the true musical stature of some of his greatest scores and will hopefully help to bring about a renewed interest in the composer. This essay merely attempts to provide a brief introduction into the life and work of Sir Granville Bantock: though he be banished in the fabling histories of British music into the shadows of the second-rate, unappreciated, ridiculed even, and will perhaps remain ignored by many or most - floating amidst the nation's cultural flotsam and jetsam and generally judged for what is said about him rather than by virtue of an actual acquaintance with his music - it will nonetheless try to give at least some intimation of the stature and significance of his work. Such is the charm and grandeur of GB's music - despite its superficial and encyclopaedic mythologising - that it can reinvigorate and sustain, for all the historical and geographical limitations which frame it, the passions of even the most wearied and satiated of open-hearted musical sensibilities. Bantock warrants far more from the country to which he gave so much, and in a deserving spirit of generosity, his music should be freed from the stale blinkeredness of our cultural treadmills; his weathered laurels discarded and replaced with a new sweeter smelling wreath.

Granville Ransome Bantock was born at 44 Cromwell Road, Notting Hill in west London on 7th August 1868. His father, George Granville was an eminent Scottish surgeon and gynaecologist and at one time President of the Royal Gynaecological Society: born amidst the tragic circumstances of the Scottish clearances on the estate of the Duke of Sutherland, for whom his father eventually became laird and whose common name both he and his son bear, he seems to have cut a somewhat imposing figure: he was obviously made of stern stuff and a man of undoubted principle as he took on Joseph Lister in a famous scientific debate over surgical disinfectant and, after some tarnishing of his reputation, won. While hardly quite like that of the Pontifex family's, GB's relationship with his father seems to have been very much indicative of the cool emotional sobrieties that so appear to characterise, at least in contrast to our own, the permitted middle-class father-son probities of the epoch. However, if the pictures of Bantock family life - cricket in the upstairs passage, train sets on the floor, animals of various kinds including snakes and white rats and later a monkey, roaming the house - are in any way true, GB's childhood home may be considered to have been a healthy, child-centred environment, if not to say downright liberal and less typical of the time. Indeed this more fun-loving and immediately life-affirming atmosphere would appear to have been provided by GB's mother, Bessie, from whom GB undoubtedly acquired some of his more characterful and endearing, not to say eccentric and sometimes obviously annoying, habits. She was from an East Anglian entrepreneurial Quaker family and, in contrast to her somewhat severe and dignified husband, she is portrayed as a woman of vivacious temperament, full of the passions of life, with a particular love of the theatre and a taste for the lavish and the munificent: she certainly seems to have provided the more artistic environment which helped to reflect GB's own eventual musical calling. Both GB's younger brothers were to enter into theatrical careers. As a child, however, GB himself showed only a passing interest in music and shirked his piano lessons: he was not the most conscientious of workers at school either and from the few reports we have there is a faint air of the mischievous dolce far niente of youth. Certainly it was not until his teens that GB acquired the all-abiding musical intent that forced him to clash with the more mundane destinies envisaged for a reputed doctor's son's life. Almost par for the course, GB's entry into the musical world followed a period of paternal opposition and it was obviously touch and go for a time. At first his father insisted on a career in the Indian Civil Service, but he managed to avoid the examinations through illness, real or otherwise. GB was then forced to study chemical engineering at the London City and Guilds Institute in South Kensington: but instead of pursuing scientific knowledge he simply took his own course and poured over scores at the Museum near by and - finger on the pulse - developed an all-abiding passion for the 'modern' music of Wagner and Liszt. At this point, que sera sera, Bantock senior, finally realised a lost cause when he saw one, and with the persuasive intervention of the Institute's Principal and a family friend, he sensibly permitted his stubborn eldest son to have some private lessons in harmony and counterpoint at the Trinity College of Music. GB finally entered the Royal Academy of Music on 22nd September 1888 at the age of 20 to begin life in the art for which he felt the more obvious and immediate calling. GB's main subjects were composition and harmony under the endearing character of Frederick Corder (himself an ardent Wagnerian), with secondary studies in clarinet, violin, viola, horn, tuba, piano, and organ: he also played the drums in the college orchestra and was a member of the choir. Though he was no rare-ripe musician and a comparatively late musical developer, at RAM he soon set about kindling his new artistic ambition: now in his element and with unreigned energy, if not bravado, he quickly revealed himself a highly productive and conspicuous talent and it did not take him long to make his mark. Despite an almost flagrant musical naiveté, GB at least showed enough musical nous, or as Corder put it, 'promise ... for at that time he knew nothing at all', to be awarded the first Macfarren Scholarship. For all the accusations of the indiscriminate absorption of others' music and the obvious and inivitable derivative modalities of many of his early compositions, GB showed, without contradiction, an obvious individuality at least in his attitude. On an immatured wing and a quick prayer he submitted some songs, two movements of a Symphony, and a setting of passages from Paradise Lost entitled Monologues for Satan, and outclassed all others, if only for the sheer breadth and potential of his musical imagination. (He also won a silver medal for harmony in 1890.) In fact, unleashed from parental authority, GB seems to have had a brief Luciferic fancy, for he also composed a tone-poem, Satan In Hell; and with it hangs one of the characteristic Bantock tales. At a student rehearsal of the work, the orchestra, under Mackenzie's direction, began to go a little awry and the music descended into chaos. Amidst the unstately din the Professor, no doubt in some exasperation, turned to query the composer himself: 'What does this mean? 'That's hell, sir', came the swift reply. Indeed such was GB's student talent that his music was not merely being regularly played at RAM (including the unprecedented step of a complete concert of his music during the summer of his leaving), but also being performed at public concerts. The summer of 1892 was in fact quite a watershed in GB's life as July also saw the first of GB's compositions to be published: the vocal score of The Fireworshippers and an album of piano music. Perhaps more significantly Caedmar and the Overture to The Fireworshippers were both taken up by Manns at Crystal Palace, the former in 1892 and again in 1894, the latter in 1893: this was one of the most prestigious venues of the time and these concerts can be said to mark his first real entry into the musical society of the time. Imitating his hero Wagner, he also began to fancy himself as a librettist, and full of Eastern promise wrote two one-act operas Caedmar and The Pearl of Iran, as well as a play Phyllis, Queen of Thrace. Afflatus untamed and romance writ large, his compositional ambition began to take on delusions of conspicuous, if not grotesque, grandeur and GB projected a symphony in 24 parts on Southey's Indian poem Kehama: 14 were supposed to have been written, but just six are known in ms. and only three of these were actually published. There were too to be six Egyptian dramas: in the event only Rameses II was published and a ballet suite from the work performed. Although his musical muse was clearly far outstripping the everyday practicalities of his compositional craft, a number of critics, including George Bernard Shaw, were nonetheless beginning to notice a burgeoning star. But if GB's compositional skills were soon revealing a vigorous and imaginative, if often unrealisable, ambition, he also immersed himself in student life, seemingly with all the immoderation and unbridled unction so often associated with it. According to Corder, he helped revamp and enliven The Excelsior Society, which arranged regular talks and recitals at the homes of present and past students, and chez Bantock became a focus of musical entertainment and heated discussion, and no doubt a lot of hot air. GB was also directly involved in the founding of a student-based periodical called The Overture at RAM: he edited the first issue published in March 1890 and later contributed an article on Wagner. The New Quarterly Musical Review Bantock was appointed Sub-Professor in Harmony in 1892, but following RAM and his student musical service done, he re-entered civvy street in July of the same year with what seems like the proverbial bump and there was no academic appointment ready and waiting the Macfarren scholar. All qualified-up and no where to work, GB nonetheless kept busy correcting examination papers, writing out the odd score for others, and playing the organ, alongside continuing his own work. More notably, with characteristic enterprise and energy, he founded and edited a new musical periodical, The New Quarterly Musical Review. It began publication in 1893 and ran for three years and 12 issues. GB's warming and attracting personality was obviously at its best, as he managed not only to get a lot of needed (and unpaid) help, especially whilst he was away touring, from friends and fellow students, such as H.O.Anderton (his first biographer and his 'secretary' for many years) and William Wallace, but also to attract a not inconsiderable array of musicological talent, young and old, onto its pages. A few years later, GB and William Wallace did try to revive it, but it was not to be. By August 1893 GB had managed to gain a job as the chef d'orchestre in an opera company touring the provinces with the burlesque, Bonnie Boy Blue. This was followed by a more prestigious appointment for 'the Guv'nor' himself, George Edwardes, as musical director on two tours performing In Town and A Gaiety Girl to large and appreciative audiences around the country. This led in turn to an even more princely task with the Gaiety Company, this time conducting a musical entourage performing across two continents and involving a complete circuit of the globe. Leaving London on 1st September 1894, the Gaiety girls and boys successfully played A Gaiety Girl to packed auditoriums in the major cities of the US and then in Australia where more pieces, including In Town, The Shop Girl, and Gentleman Joe, were added to the repertoire. GB did not return to native heath for another fifteen months, but clearly very much enjoyed his trip, and even wrote a book about it. He was hardly one to deny himself the pleasure of a 'bargain' and he must have had a large cabin on the boat back for precisely where he stored all the acquired spoils and treasures of his colonial trading, including a monkey (GB was always a great animal lover) would be hard to say. Though the music itself had few pretensions to being deep and meaningful and would hardly furrow a lofty brow, its own artistic attainment pleased and entertained, and the tour obviously turned into one of the most memorable and learning experiences of his life, not least in the acquirement of the immediate and everyday practical skills of conductorship and working with other musicians, and finding out what worked well in the concert hall rather than what looked clever on score paper and merely impressed his peers. For a time it looked as if, like his brothers, GB were now destined for a career in 'Light Music'. With his brother Leedham, he wrote a couple of musical hall songs - he had one notable 'hit', Who'll Give a Penny to the Monkey? (in which his monkey, Nantze, or Nancy, was given mention) - and worked on three other musical comedies right up until the turn of the century. Indeed in April 1896 GB was declaring himself 'utterly sick of serious music' and during the autumn of 1896 he was once again on the road, joining a tour of Stanford's Shamus O'Brien (Henry Wood had been conductor on its first run) and performing in north-west England and the major cities of Ireland. The following May, with still no 'serious' academic post in the offering, GB was back in the pits, this time conducting incidental music for a series of French plays at the Royalty Theatre. But as much as GB was undoubtedly attracted to and bedazzled by the vibrancies of theatre life - and he continued to write for the stage at various times throughout his life - he was too much besotted with the elevated glories and grandeur of the notion of Art to compromise the acquired nobilities of his ideals to the extent of foregoing the 'serious' consecration of his muse. During this period of conducting and touring GB's music had only rarely been performed, and so the composer decided to organise a concert of his own, which took place on 15th December 1896, probably with Bantock senior's financial assistance. This featured three GB pieces, Overture: Eugene Aram, Songs of Arabia, and The Funeral from The Curse of Kehama and, with characteristic generosity, works by friends and fellow students: with full programme notes and an introductory 'manifesto' written by his pal, William Wallace, the Queen's Hall concert created quite a furore in the press for its radical, declatory tone. With the dust still hardly settled, another notable concert of British chamber music, featuring GB's Songs of Japan, followed in May 1897. Yet, by June he was seemingly back in the realm of 'Light Music', all ready to conduct a military band in the 'new' resort of New Brighton on the Wirral.

The Tower New Brighton was taller than Blackpool's and, rising up from a large circular ballroom at its base, it constituted the centre piece of an amazing complex of entertaining facilities - a veritable Disneyland of its time - which attracted punters from far and wide. Though light, dance, and military pieces were necessarily an essential part of his musical provision, GB immediately started introducing 'modern' orchestral works - Wagner, Tchaikovsky, and Rubinstein were notably conspicuous - alongside the standard, more familiar works of the classical and romantic repertoire in his programmes. Even more daring, he soon began devoting whole concerts to contemporary British composers, some of whom were invited to come to the resort to conduct their own works. Soon both local and national press were acknowledging his skill as a conductor of a fine orchestra, and New Brighton quickly began to acquire a nation-wide reputation as a centre of pioneering musical excellence, visited by some of the major composers and performers of the day. GB played host to a whole number of leading musical lights, including Stanford, Parry, Corder, Mackenzie, and Elgar, as well as promoting other lesser known, younger, contemporary composers like Wallace and Holbrooke: many of these figures were to remain friends for many years. Strangely, but with an admirable and characteristic lack of self-publicisation (so essential today), he only ever programmed a handful of his own compositions at New Brighton. The achievements of his work at The Tower and his contribution to the musical life of the nation were soon being recognised abroad as well as at home. In February 1900, indicative of his growing prestige as both a composer and conductor, GB was invited to Antwerp to conduct a concert of British music, which included the premieres of his Helena Variations (dedicated to his young wife) and Russian Scenes, plus the overture Eugene Aram and the orchestral scene, Jaga-Naut, from Kehama: this was followed by a second concert in the same city a year later at which the impressive orchestral tone-poem on Southey's oriental tale, Thalaba the Destroyer, and the Songs of Egypt, and Songs of Arabia were performed. Although GB's time at New Brighton was obviously very much taken up with his conducting duties (and he also took up the conductorship of the Runcorn Choral Society for a short time), he nonetheless managed to complete a number of new works: Helena Variations; the final three volumes of Songs of the East, Songs of Persia, Songs of India, and Songs of China with words by Helen; Elegiac Poem for cello and orchestra; plus the previously mentioned suite for small orchestra, the Tchiakovsky-like, Russian Scenes, whilst he still continued to work on his mighty Curse of Kehama and another sprawling conception called Christus, subtitled a Festival Symphony. It is probably reasonable to say that by the time GB left New Brighton he had well and truly arrived on the contemporary musical scene. Over the next two decades GB was to establish himself, both with his music and his administrative and academic activities, as a central figure in the landscape of British music. Soon after leaving the North West GB became conductor for the Liverpool Orchestral Society (for whom Sibelius later came, at GB's request, to conduct a concert): but New Brighton was never again to achieve the reputation it had acquired during the last three years of the C19th. Birmingham and Midland Institute Circumstances at the entertainment complex had began to change during GB's final season on the Wirral, and his presence there was becoming viewed less favourably by some of the management committee. It was time to move on, and in 1900, backed with recommendations from Mackenzie, Stainer, Parry, Stanford, and others, he left the banks of the Mersey to take up an appointment as the Principal of the Birmingham and Midland Institute School of Music. He was also offered a post at RAM, and if many others would have inevitably gravitated back to the musical hub of London in search of more reputable shadows, GB had no such insecurities. Somewhat enigmatically, if not inappropriately, he informed Mackenzie, quoting once again from Milton, that he would rather reign in hell than serve in Heaven.

But if GB still invested himself with a Promethean radicalism, it was Birmingham

that was to remain his home and musical hearth for the majority of his remaining

career. Hamilton, the couple's third son, and Myrrha (pronounced like 'mirror'

by the family) were born not long after the family's move south. There were

some early unsettling changes of house before more lasting abodes at Broad

Meadow in King's Norton, Elvetham Road and Wheeley's Road in Edgabaston,

and finally Metchley Lodge in Harbourne (incidentally the only one of these

homes which has not been demolished and suitably bears a blue plaque

commemorating his stay there). There were continuing money problems too -

not helped by GB's prodigious prodigality - with the family periodically

having to sell off all sorts of acquired artefacts to pay accumulated bills;

books especially (GB was always a ferocious reader) left the house at regular

intervals, though sometimes gratis to libraries with which the composer

had become associated. Nonetheless GB, for all his restless energy and notorious

eccentricities and unconformity in terms of the strict punctilios of the

times, soon settled into a more ostensibly conventional pattern of family

life and the domesticities of home-making; holidays (the family eventually

acquired a second home in north Wales), playing games with the children,

entertaining family and friends, feeding his beloved animals and pets, and

the occasional party; set alongside the endless rounds of appointments and

meetings which his involvement in so many musical organisations, clubs, and

societies entailed - the list of his acquired presidencies and vice-presidencies

during his life is numerous. Yet in retrospect the appointment at Birmingham

was ultimately to prove both a blessing and a hindrance to his own status

as a composer, and indeed as a conductor. GB's position at the forefront

of British music was eventually to become less conspicuous and, though his

music, old and new, was still frequently and honourably played in the country's

concert halls and abroad well into the '20s, the Great War proved, as in

so many things, a cultural finial, not least in the taste and manners of

musical appreciation. But, despite the

The Midland Institute had its origins in the enfranchising radical and liberal politics of the mid-C19th and the desire for the more widespread dissemination of scientific knowledge, especially amongst working-class men and women, and had become an important, progressive, and much respected educational establishment in the city. But from its humble beginnings in 1854 it had changed its character over the intervening years and moved from an institution dominated by industrial and scientific priorities towards one of more artistic learning, and music had already come to take over a fair share of the rooms of its impressive building, which stretched from Edmund Street to Paradise Street. It was during this time, amidst the decades of the School's highest prestige, that GB arrived in Britain's second city to set about creating and ensuring a vibrant centre of musical excellence on the Midland plateau. The authors of the Annual Report of 1900 were soon much impressed by the appointment: 'He has entered upon his work with enthusiasm ... and is transforming the School from a number of unconnected classes into an organised School'. There were a students' orchestra and choir, regular chamber music recitals, as well as an opportunity to indulge in grand and not-so-grand opera. A Students' Annual Concert held in the Town Hall at the end of each session began in 1901 and ran for years to come. GB occupied a small room at the top of a flight of stone steps and soon more and more students were ascending the 'Golden Stairs' to consult with their reputed maestro as numbers at the School immediately increased rising to a peak in 1920. In 1902 Elgar became Honorary Visitor of the School and such figures as Adrian Boult, Rutland Boughton, Joseph Holbrooke, Julius Harrison, Clarence Raybould, and Ernest Newman were all at various times on the staff of the Institute. With his natural and persuasive charm, GB embroiled figures of wealth and municipal power into the activities of the school and it became an auspicious feature of the city's cultural life. With Elgar himself installed as the first Peyton Professor at the nearby University in 1904, Birmingham naturally began to become a considerable force in the country's musical geography. Such was GB's own energy that he also managed to add the Wolverhampton Festival Choral Society, the Birmingham Amateur Orchestral Society, and, replacing Elgar, the Worcester Philharmonic Society to his list of conducting affiliations.

GB was of course soon active in the musical life of the Midlands and was notably instrumental in attempts to found a permanent symphony orchestra in the city of Birmingham. Following many short-lived musical ventures and numerous meetings and discussions involving municipal powers, local philanthropists, and other well-known figures in the world of music, he helped conceive the Birmingham Philharmonic Society, which was active prior to the war. He was also involved in setting up Beecham's New Birmingham Orchestra in 1917. He then played a major role in the formation of the City of Birmingham Orchestra, the immediate precursor of the CBSO; and suitably, after its official establishment in 1919, the first work played by the CBO in September 1920 was GB's Overture: Saul.

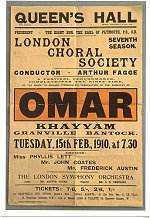

Literature and Classical Antiquity Classical Antiquity was also an integral element of a good proportion of his output. The ineffable and exquisitely powerful Pagan Symphony completed in 1928 may be seen as a musical depiction of Arcadia and the score is suitably prefaced with a quotation from Horace; as is his (less immediately appealing but still fine) Third Symphony, The Cyprian Goddess, subtitled Aphrodite in Cyprus, completed just over a decade later in Fiji. The Sappho Songs for contralto and orchestra were a beautiful musical setting of Sappho's lesbian poetry, adapted and effectuated by Helen, and are amongst his finest achievements. He also wrote incidental music for Greek plays whilst at Birmingham and after, including Electra, Oedipus Coloneus, The Birds, and The Frogs which deserve exploration. Although he was no practising Christian, GB had written a number of religious pieces prior to his arrival in Birmingham: but the literature of the Bible continued to hold a fascination as testified by his Vanity of Vanities, adapted from Ecclesiastes and Seven Burdens of Isaiah for unaccompanied chorus of male voices. Similarly, classic literature, poetry and plays old and new supplied him with much appropriate material for his music and he produced such works as Dante and Beatrice, Pilgrim's Progress for soli, chorus, and orchestra, incidental music for Bennett's Judith, plus settings of Browning, Tennyson, Blake, and Burns, amongst many others. Naturally Shakespeare was a source of musical stimulation too with the dramatic tone poem King Lear and his incidental music for Macbeth. His musical outlook was cosmopolitan, yet GB was also very much a British composer and it was his ancestral home especially that proved to be just as deep a spiritual motivation to his music as the passions of a broad and cultured imagination. He composed and arranged music inspired by all the musical nations of these isles, but it was Scotland and Hebridean folk music in particular that provided one of the most fruitful and plentiful springs of musical motivation and they undoubtedly impelled him to some of his most glorious music. For a while during the 1910s all things Scottish became an abiding passion and, according to GB's daughter, the family were all but taken over with GB's new found inspiration, following a holiday in the Highlands: Angus learnt to play the bagpipes and Hamilton danced the Highland Fling and the Sword Dance whilst wearing the Munro tartan (GB's paternal grandmother was a Munro). Through Rutland Boughton, GB became a friend of Marjory Kennedy-Fraser, and her famous (but in some Scottish musical quarters much reviled) collections of Songs of the Hebrides (1907, 1917, 1921) became an important source of thematic material (GB actually did four of the arrangements included in Volume II himself). By the end of his life Bantock had produced a whole series of compositions that made use of Scottish legend and evoked the landscape and spirit of the Gael, often quarrying Kennedy-Fraser's albeit sometimes heavily corrupted versions of Hebridean folksong: these works included the stunning Hebridean Symphony, The Sea Reivers, The Seal-Woman (a two-act opera with a libretto by Kennedy-Fraser, who sang the role of the 'Old Crone' in its first performance at the Repertory Theatre, Birmingham in 1924), and two works from later years, the utterly delightful Celtic Symphony (the glory of his last years) and Two Heroic Ballads. Other pieces also looked to Scotland for their inspiration, such as two suites for string orchestra, The Land of the Gael and Scenes from the Scottish Highlands, a Scottish Rhapsody for orchestra, Coronach for strings, harp, and organ, a Celtic Poem for cello and piano, Three Scottish Scenes for piano, and Pibroch for cello and harp or piano - all containing some quite charming music and very much deserve to be recorded particularly at this opportune time. There were too arrangements for a whole number of Scottish and specifically Hebridean songs, notably Sea Sorrow, which was successfully recorded many years ago by the Glasgow Orpheus Choir, of which GB became President. Another particularly impressive musical aspect of GB's life during his years at Birmingham gradually seemed to take hold of a significant, if not disproportionate, part of his energies. The Association of Competitive Festivals had been formed in 1905 and the Festivals Movement rapidly grew in importance during the first decade of the C20th to become a significant aspect of the musical life of the nation during the early decades of this century. It especially appealed to the composer's strong sense of common humanity and inwrought 'democratic' political virtue and GB became active as honorary director in the formation of the Birmingham and Midland Festival, which began in 1912. Along with other familiar figures, such as Walford Davies, Harry Evans, Hugh Roberton, and Dan Godfrey, GB was soon a frequent and well-known judge and leading figure at festivals throughout the country and eventually abroad too. He wrote numerous part-songs, notably for the brilliant choirs that had sprung up in the industrial cities of the north, and he became one of the country's foremost choral composers during this period, with his songs and arrangements being a common feature of the repertoire in the 1920s. For a time GB became completely besotted not simply with choral music but more specifically with a cappella singing, and he briefly gave up orchestral music altogether to compose, amongst other works, two choral symphonies Atalanta in Calydon and the aforementioned Vanity of Vanities, both of which can legitimately be described as a wholly novel, if not radical, though perhaps not entirely winning, experiment in the use of the human voice. With GB's services becoming increasingly in demand and as he began to undertake more and more tours around the country and abroad, his immediate and practical commitment to the School of Music and the University appears to have gradually slackened somewhat. Vacations were increasingly spent travelling and officiating. In 1923 GB took the summer term off to travel to Canada to adjudicate at four Musical Competition Festivals and at the beginning of 1930 he took a full year's leave of absence to tour abroad as examiner for Trinity College of Music: this also included conducting and attending at a Bantock Festival given in Durban by the Municipal Orchestra directed by Dan Godfrey Jr..

However, despite his fall from favour in the years leading up to the Second World War, following his retirement from Birmingham in 1934, GB was far from inactive and he undoubtedly remained a revered figure in the musical world, much vetted and still commanding the conferred entitlements and honours of his acquired stature - and after all he had more than paid his dues. Sir Granville and Lady Bantock moved to London and, at the age 65, GB continued his work for Trinity College as teacher, examiner, and ambassador, touring regularly at home and abroad, including trips to the Americas and the West Indies, and another visit to Australia. He became Chairman of the Board at the start of the war. After a while the Bantocks moved out to Buckinghamshire, to Mead Cottage, at Gerrard's Cross, but perversely, as bombs rained down on the people of the capital, they returned to London, and on at least one occasion narrowly avoided one of the Luftwaffe's bombs. After the war they moved back to Birmingham to live next door to their son, Raymond, at Sheriff Cottage, GB still reading, still collecting, still composing. Fortunately, for all his neglect, his own muse and musical intent did not desert him, and, although perhaps not surprisingly less prolific, he never stopped writing music. He still had something to say and even lived, despite failing health, to be able to record some of his own works, and saw a portion of his music issued on 78s by Paxton, including the short but masterly Celtic Symphony which had him quite gloriously looking back to previous sources of inspiration and is undoubtedly the high spot of his final years - a genuinely masterly and potentially very popular creation. There were too a couple of overtures for Greek plays, and, still looking eastward and paying homage to a faraway culture, he scored the wonderful Four Chinese Landscapes. There were too a set of fun, but less distinguished, 'Mood Music' pieces for the Paxton label, containing exotic titles such Persian Dance, Oriental Dance, Oriental Serenade, Cobweb Castle, and Desert Caravan. In 1942 and 1943 he wrote a number of works for brass band: but, though this late enthusiasm characteristically mirrored his commitment to the earlier choral movement, it made little impact on the overall musical scene; though two earlier scores, Prometheus Unbound and The Frogs of Aristophanes, are still in the catalogue. Eleven months after conducting and recording a number of his own works and a piece by Holbrooke in the Kingsway Hall, he died at the age of 78 on 16th October 1946 whilst in hospital at All Saints, London, a pile of books and his musical notebook still at his bedside. GB was cremated at Golders Green and, as their father had requested, his ashes were later scattered to the wind by Angus and Raymond on top of Moelwyn Mawr in north Wales, near where they had spent so many happy family holidays. Thus ended a musical sojourn which had begun back in the last decades of the previous century. Helen lived on at Sheriff Cottage for another fifteen years until she died at the age of ninety-three. Granville Bantock was a broad-minded and full-hearted character, genial, kindly, and generous to friends, seemingly almost childlike in his enthusiasms and unending curiosity; and though he recognised expediency and often a pragmatist, he was in many other ways an idealistic and radically nonconformist figure, especially when one considers the cultural strictures and conventions of his age. His eccentricities (probably partly affected, despite what his daughter says) were charming or exasperating according to taste. But, for all his obvious saving graces, GB was certainly not without the curses and personal imperfections of mortal life. He had a darker, unvirtuous side. There were palpable streaks of malevolence and moral ambivalence in his character and he was no ascetic, and some of his behaviour had deeply unhappy consequences for those closest to him. (There is an occasional intimation, though no concrete evidence that I can find, that he also inhabited another very hidden, private world.) He undoubtedly had a keen eye for a pretty lady and had one known extra-marital liaison with the singer Denne Parker in the 1920s which produced one child. This had a profound affect on his wife and children, all of whom obviously loved and cherished him deeply: the wounds of this affair were it seems never entirely healed and may in part account for his subsequent frequent long spells away from home. Professionally, he had often spoken his own mind. He had been immersed in numerous musical organisations, such as The Musical League, and, by the nature of things, been party to a few political shenanigans within the musical world. He tirelessly campaigned on behalf not only of British music (several other neglected British composers benefited from his continual support, notably his friends Havergal Brian and Holbrooke), but also of contemporary composers abroad, and he had openly criticised the BBC for their conservatism and narrow musical policies. But, despite his personal flaws, such was his charmed and friendly character and his obvious and primary commitment to the good of music in general that he made few enemies in his life. Soon after GB's death Boult wrote: 'Surely there was never a musician who made more friends than GB'. Though, by all accounts, emanating an air of greatness, he played the man of considerable humility, and whilst his idiosyncrasies and humour, sometimes almost cruel, often baffled and tried the patience of many of his friends, his overwhelming spiritual positiveness, his humanity, and his lack of jealousy, quite apart from the gift of his music, had him much loved and admired until his dying day; indeed you would be hard-pressed to find a bad word said about him from any of his fellow composers and musicians - even Delius and Holbrooke had nice things to say about him! Somehow he managed to find time to befriend, socialise and correspond with many of the leading artistic and political figures of his day, far too numerous to labour mention. Despite his undoubted failings as a man, there was a temper of simple human virtue which blessed a good proportion of his behaviour: he was a learned, scholarly man, and as the years passed he did acquire a certain air of sagacity and serenity, which contrasted with the familiar blusterings and occasional petulances which were also a part of his nature. According to his daughter, the towering rages to which he could succumb in younger days became much less frequent in later years. The influence of Eastern religion and ancient philosophies and the comforts of literature - which have so often been cause to cynically disparage his music - were not, as some may simply like to gather, just an egocentric and superficial pretence: though he was no budding Buddhist and his spirituality did at times possess a certain hollowness to it, they had a palpable reflection in his nature and the quality of his behaviour. As he grew older and found his music played less and less, there is to be sure an undoubted strain of bitterness, an occasional milligrubs over the disinterestedness of the musical powers, along with an understandable general exasperation with the ways of the modern world, which, as for so many of his generation, seemed to contrast with the apparent Edwardian pre-war 'golden age' of his halcyon years: but, if he certainly had cause to feel hard-done-by and bemoan his luck, there is little sign of him wallowing in self-pity, and he remained a man of abiding optimism and idealism to his dying day. However, though the charisma and genius of GB shine through the years, the story of the cultural rise and fall in the appreciation of his most prized gift - his music - remains marked by underlying pathos. Following his death, his name and his work almost immediately slipped into real obscurity, and after the 2nd World War his compositions were only occasionally played. Over the past number of decades Bantock has generally only really been known, if at all, for two works: the delightful overture Pierrot of the Minute and, more especially, Fifine at the Fair, one particular piece that was championed and recorded by Beecham. There was a flourish of interest in his music in 1968 on the occasion of the centenary of his birth, but it was all too brief and failed to herald a Bantock renaissance: the established fact of his virtual cultural oblivion had by this time sadly become all too easily equated with the unestablished fact of his musical mediocrity, and his consummate scores lay ignored and dusty. Yet his neglect owes little to the intrinsic quality of his work, and much more to do with the unluck or misjudgements associated with the blinding mythic tyrannies of taste and fashion. He was a man who vigorously immersed himself in many of the cultural preoccupations of his age and this was often reflected in his music: and other composers often undoubtedly provided immediate inspiration, such as Wagner, Lizst, Strauss, Elgar, and Tschaikovsky. But such oft-repeated, feeble-headed truisms forwarded in the malleable logic of depreciation do nothing to abrogate the supreme summation that so obviously inheres so much of GB's own work. Proper acquaintance with his music does reveal the capacious integration of his own musical identity. There is a quality in his music that does undoubtedly rise above and endure far beyond the cultural immurement of its creation; that remains a voice strong and clear enough to ring down the generations. If he was seemingly sometimes too radical for his own age but then too conservative for the one that followed, perhaps the cultural dialectic of our own age can reach a more mature and unblinkered demeanour towards the enjoyment and appreciation of his music and shed the ridiculous verbiage and obfuscations of critical special-pleadings. His music, lyrical, beautiful, and vibrant, has a tremendous imaginative and visual quality, and the kind of imagery that helped make Bantock's music so striking and expressive is in some ways very much in accord with the musical sensibilities and fancies of our own age. It is a great pity that Bantock was never asked to write for the cinema. His music is already beginning to be used occasionally on our screens and, due to the fine new releases on CD, it is now starting to find it's way more frequently onto the radio; though sadly not yet into the concert hall in any significant mannner. However, it would only need one of his works to be used in a successful film or TV series, or for a certain piece, such as the short but mighty Celtic Symphony, to be consistently plugged on the radio for his music to see a complete resurgence and to undergo its long awaited re-establishment in the cultural dynasties of the nation's music. As a final word it is perhaps worth quoting the tale of the 'Perth Express' as related by GB's friend, Sir Hugh Roberton. 'Fond of fun, fond of jokes (practical jokes too), G.B. would have no truck whatever with Scottish humour of any kind. This, in itself, was his greatest joke. Tell him a Scots story, and he would turn on you a smile both childlike and bland, and ask for an elucidation. Example. One day I was telling him the rather hoary one of the inebriated Scot reeling about the edge of a station platform and being constantly pushed back by a porter with the remark - "Stand back there! Did I no' tell ye that the Perth Express was due to pass in a minute?" Exasperated and contemptuous, the drunk eventually turned and hiccoughed to the waiting passengers - "He's awfu' frichtened for his Perth Express!" An utterly blank Bantock. Then, after a pause - "tell me, Elder, I want to get the thing clear; was the express going to or coming from Perth?" 'The sequel to this was funnier than the story. From all parts of the country (G.B. was on an adjudicating tour) came post-card after post-card asking this question and that about the Perth Express. Was it really an express? Did it have two engines or one? Did it have a dining car? Was the driver a native of Perth? Did it finally reach its destination? And then, weeks later, to wind up, came a telegram from Euston Station - "Have enquired here of the traffic superintendent - no such train as the Perth Express." And that was the man, ever expansive, ever the boy in him coming out.' Enough words - the music says all that really needs to be said. Having been asked to contribute to the Bantock Memorial Fund following GB's death, George Bernard Shaw aptly replied: 'Never mind tributes - play his music'. If played, the ineradicable greatness of his ffinest music will surely one day win out and his life's work finally properly vindicated. Acknowledgements Thanks are due to Anton Bantock, Dr. Cuillin Bantock, and Ron Bleach.

© Vince Budd February 2000, South Uist, Outer Hebrides

|