Monteverdi, Orfeo: English

National Opera, 15.4.2006 (ME)

‘L’Orfeo’ was not the first

opera, that honour belonging to Peri and Corsi’s

Daphne of 1598, but it was Monteverdi’s

first opera and certainly the first ‘great’

work in that genre. When it was premiered at the ducal

palace in Mantua in 1607, the composer used a small

cast of around nine or ten singers, ideal for such

an intimate space and for the depiction of such deeply

personal emotions as love and loss: the composer’s

own wife, the court singer Claudia Cattaneo, died

in the same year. Today Orfeo occupies a central

place in the repertoire: ENO’s last new production

was in 1981, with Anthony Rolfe Johnson in the title

role – that was a fairly conventional affair,

classically restrained in style, very different to

this latest one by the modish Chinese-American Chen

Shi-Zheng, in collaboration with the Handel and Haydn

Society of Boston.

Monteverdi’s most remarkable legacy was surely

his invention of the stile concitato, or ‘agitated

style,’ a form of musical expression designed

to give voice to extreme emotions which he perfected

in the later Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda,

and this version of Orfeo served more than

anything else to remind us of how original that concept

was: it was not so much the stage pictures as the

sound world which Lawrence Cummings, the orchestra

and singers had created, which made for a genuinely

thrilling evening. The regular ENO orchestra joined

forces with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment,

and they were performing from an edition of the score

based on facsimiles of 1609 and 1615: instruments

used included historical copies, tremendous attention

had been given to the detail of Monteverdi’s

singing style, and, as the conductor says, this enabled

‘the intonation and sound world of the seventeenth

century’ to be ‘absorbed as if by osmosis.’

It is not easy to transpose that which was created

for a private space into something suitable for the

vast cavern that is the Coliseum, but it is a tribute

to Cummings and most of the singers that one was seldom

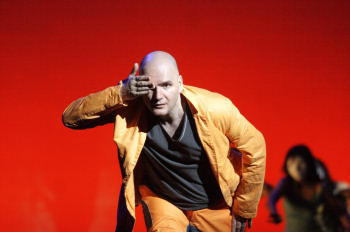

conscious of the disparity. Such is the virtuosity

required of the singer of the title part that few

singers are up to it unless you are willing to pretend

that a pared-down or otherwise adapted version of

the role is acceptable: there is of course a lot of

that about, but if what you are seeking is no-holds-barred

virtuosity coupled with a willingness to throw himself

into whatever the director has decreed – or,

putting it bluntly, the ability to do idiotic things

with the body whilst doing glorious ones with the

voice – then John Mark Ainsley is your one stop

shop. His voice is not large, being far more suited

to a space such as a room in a ducal palace than a

1500 seat opera house, but then the role itself is

not in the big bow-wow style.

I question the notions that Orpheus must be ‘sent

up,’ that he is some sort of pop idol with a

grievance, and that he should ascend to the skies

in quite so mundane a manner (harnessed like an aid

parcel of rice travelling in the opposite direction)

but given all that, you could just shut your eyes

and listen to some of the most agile, daring and expressive

singing anyone could hope to hear. I have previously

described the aria ‘Possente Spirito’

as the most taxing nine minutes of any singer’s

life, but Ainsley makes it sound as natural as such

complex music can be: when Caronte falls asleep you

are persuaded, not that Orfeo has bored him into slumber

but that he has fallen into a strategic doze so that

the poet-singer can cross the river and achieve his

desire. Ainsley is less convincing in his final scenes,

perhaps because the production makes too much of his

character’s egotism and self-dramatization,

but elsewhere he is peerless, whether joyful in the

ecstatic music of the first act or numbed by grief

in ‘Tu se’ morta, se’ morta, mia

vita.’

He is supported by a very fine, mostly young cast:

Elizabeth Watts sang with crystalline clarity as Music,

although the part of Hope lies a little low for her;

Wendy Dawn Thompson was a wonderful Messenger, dignified

in her sorrow and conveying every nuance of her doleful

story – both these singers are ex students of

the RCM and it is good to see them on the ENO stage,

reminding us not only that the RCM continues to provide

singers of outstanding talent, but also that our national

opera company is fulfilling its role in terms of nurturing

them. Tom Randle was a supportive ensemble member

as well as a noble Apollo, if a times a little underpowered;

Stephanie Marshall was a finely seductive Proserpina,

Jeremy White an unctuous Pluto, and Brindley Sherratt

a finely characterized Charon. Ruby Philogene seemed

over-parted as Eurydice. There was much fine singing

from the ensemble (more usually referred to as ‘shepherds’)

with Tim Mead and Toby Stafford-Allen being especially

noteworthy.

There was much to like about the production, although

those who saw Trisha Brown’s version in Brussels

might not find this one particularly original, since

not only the basic set but the use of gesture, movement

and dance were very similar. The lighting, by Scott

Zielinski, is wonderful: subtle, exciting and wonderfully

varied, his designs create worlds of murky darkness

suggestive of mysterious other realms, or of glorious

colour-filled spring and summer fields. Much of the

stage design, too, is finely done, with Charon’s

deathly ferryboat being especially evocative: the

director revealed his own fascination with death and

funerals in a recent interview, and this is very intimately

shown not only in that scene but in the rituals surrounding

Euridice.

Where I part company from this director is his use

of so many dancers, and his apparent idea that the

world of Western celebration must be suggested by

– yet again – youths in T shirts swigging

from bottles of Bolly: that sort of thing is so RSC

circa 1989, and it does nothing to further the drama.

The dancers are all graceful, beautiful and elegant,

but they seem to be used as eye candy rather than

integrated into the whole; my own taste in such things

is to let the music speak for itself through the singers,

rather than being given the impression that we are

unable to sit and listen to singing – we must

somehow have vibrant colours flashing before our eyes.

I found the scene between Orfeo and Apollo to be lacking

in dignity, although of course the singing compensated

for much. As you might expect, I loathed the penny-

plain, deeply unpoetic translation.

Orfeo has not lost its power to move us, and

when it is sung and played like this, in a production

which, however much I might question some elements,

is redolent of deep love for, and commitment to the

work, it cannot fail to remind us of the power of

great music to change our perceptions. It was a joy

to hear the quality of playing which Cummings obtained

from the orchestra, especially from the lutes, recorders

and trumpets, although what a shame it was that two

ladies sitting near to me, and obviously connected

to the production or the house in some way, so they

should have known better, felt it necessary to continue

their ‘mwah mwah’ socializing during the

opening fanfare, as though it were a mere piece of

background music. There was clearly a big ‘fan

club’ presence for the director, to judge by

the roars he received when he took his bow –

significantly, he occupied the central position in

the ‘line-up,’ whilst the singers –

even Orfeo himself – took a modest side part.

The ascendancy of the director being made manifest?

I hope not, since this above all is an opera which

depends upon the strength of its singing, and it is

in that area which this version of it is most obviously

successful.

Melanie Eskenazi