Edvard Munch - A Promise Unfulfilled: Main Galleries and The Sackler Wing, Royal

Academy of Arts, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London. 1st

October – 11th December 2005 (AR)

He who fights with monsters might take care

lest

he thereby become a monster.

And if you gaze for long into an abyss,

the abyss gazes also into you.

Beyond

Good and Evil, Friedrich Wilhelm Nietszche

The most revelatory aspect of the Royal Academy of

Arts current exhibition ‘Edvard

Munch by Himself’ is that there is a marked falling off of

powers the older and the more sick Munch became, before dying

at 80. Maybe the exhibition should have been called: ‘The

Rise and Falling Off of Edvard Munch

or ‘Edvard Munch: A Promise Unfulfilled’ as the artist never lived

up to his initial promise and potential.

Beautifully curated by Iris

Müller-Westermann, Curator of International

Art at the Moderna Museet,

Stockholm, the show is divided into six chronological sections

each revealing the relationship between events in Munch’s

‘dis-eased’ life and his angst-ridden art.

The exhibition opens with three of Munch’s early series of self-portraits from the 1880’s which

showed signs of potential genius: notably Self Portrait with

Cigarette, 1895 where the artist gives us a cold disinterested stare in a haze of drifting

blue smoke complemented by bleeding blue paint dripping off

the image: this image is cool and calculating yet full of

the dread and anxiety to come slowly leaking from the cigarette.

Also striking is his Self Portrait, 1886 which has extraordinarily

subtle scar marks made by the end of the brush cut into the

paint giving us an uncanny sensation of uneasy calm. His debonair

demeanour and stare is smug, condescending and self-congratulatory.

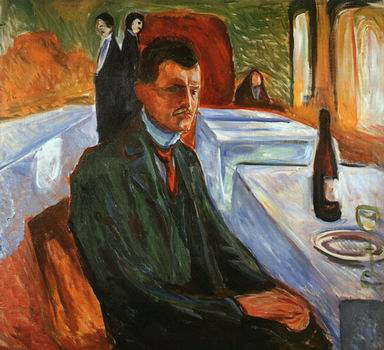

This is his finest self-portrait. A self-portrait that Munch

considered his finest was Self-Portrait with a Bottle of Wine,

1906 which depicts the artist alienated in a bar severed off

from the others around him. Here Munch and a Bottle become

unified in their auto-alienation: each alone but side by side

and waiting for each other to be poured out into each other.

Munch gives the shuddering yet serene sensation of an uneasy

calm and a barely suppressed inner turmoil: he shows us that

we can be absolutely alone amidst others.

The most disturbingly delightful image on display is Self-Portrait

in Hell, 1903, where Munch’s skin

appears flayed and in flames burnt almost beyond human recognition

with his naked body becoming a flaming torch: yet Munch does

not appear tortured at all but stands stern and indifferent

by being engulfed by flames.

Likewise a striking charcoal drawing Self–Portrait,

1912, has a fluid three dimensional sculptural quality about

it, with powerful meandering, muscular, musical lines; similarly

his musical Self-Portrait with Nude Torso, 1915 has a rugged

but fluent tautness of line missing in later works.

Bricklayer and Mechanic, 1908 is the most interesting

and successful ‘painting’ in the exhibition: by ‘paint’ I

mean non-illustrational ‘painterly’ paint where the paint

makes the image and does not merely fill in the form. Whilst

the face of the figure on the right has no features it still

stares and smiles out at you: the eyes - which are not there - are still horrible to look at.

In Vampire, 1893 and The Death of Marat 1, 1907 Munch shows his true misogynistic colours and

paranoid fear of women representing them as unevolved

alien creatures: these paintings unwittingly expose Munch’s

deeply reactionary and conservative attitude towards women

portraying them as threatening and on the verge of devouring

men.

Like Francis Bacon, Munch’s

artistic powers died years before he did and by the early

1920’s his self-portraits became watered down caricatures

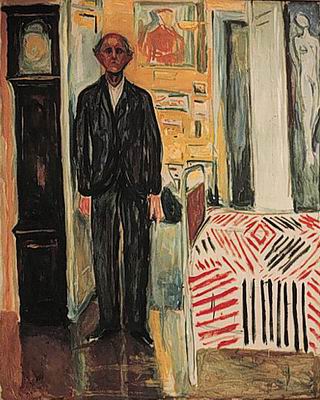

and clichés of his former works. This decline is evident in

Self-Portrait: The Night Wanderer, 1923-24, where Munch becomes

a looming ghost of his former self: there is nothing in the

eyes but the promise of death and the paint itself is dry

and dead.

By the 1930’s artistically all

is lost and psychologically Munch lost his head and thus any

sense of self-reflectivity and critical evaluation of his

work. There is no rigorous self-discipline and Munch allows

the paint to get out of control – but not like the elegant

‘ordered chaos’ of Pollock or the brutal ‘thrown chance’ of

Bacon or the anarchic ‘bravura attack’ of Corinth.

The self-portraits from the

1940’s are pitifully inept and Munch’s handling of the paint

becomes incontinent and etiolated giving the sensation of

diarrhoea whilst his drawing becomes very crude and clumsy

with sloppy brush work reminding one of John Bratby

– or a poor man’s Van Gogh

- as seen in Self-portrait with Hat and Coat 1930.

The decorative influence of Matisse can be seen in Self-Portrait

between Bed and Clock 1940-42: here Munch appears as a skeletal

zombie almost as thin as the Grand Father Clock that he stands

erect by.

Despite painting 70 self-portraits in oils over a

60-year period Munch never really developed as a self-portraitist

in the same way that Rembrandt or Van Gogh did and of these

70 oils only 5 remain of the first rank.

In his self portraits Munch never got away from illustration

(natural realism) and could not reinvent the face or the head

(they are not the same thing) in the radical way that Picasso

or Jawlensky could. There is nothing psychically or dramatically

interesting or inventive in his late self-portraits as there

always was in Rembrandt’s self-portraits. The principal difference

between Munch and Rembrandt is that the latter’s powers and

brilliance in his sheer application and manipulation of oil

paint if anything increased with old age. Munch’s poorly painted late self-portraits are embarrassingly

bad and all signs and sensations of being in the world have

long departed. The final self-portraits of Van Gogh unflinchingly

depict a disintegrating mind and are intensely moving where

the paint is poignant and alive whereas Munch’s

self-indulgences leave us strangely unmoved: we feel no engagement

and little pity.

Munch defined ‘art’ as a symptom of our 'fear of life'

and his later and weak self-portraits may be defined as his

‘fear of painting’ – of ‘losing it’ – and as he lost his head

psychologically he also lost his head aesthetically:

the paint lacked body, his head lacked a face. Whilst

his late self-portraits seek to record the artist’s self-obsessions

with his physical and mental traumas they all remain on the

same level of sensation: a mood of non-presence – of somehow

not being there at all: traces of torn traumas but devoid

of pleasure or pain: just a domesticated dullness: boredom.

Munch is seemingly ‘bored by himself’ and his self-portraits

are about being bored: boredom is his essence and not anxiety

as is often imagined. Munch was the ‘arch depictor’

of Nordic gloom, wallowing in a narcissistic misery signifying

nothing.

Munch spent the last twenty years of his life from

1922 to 1944 in exile at his house in Ekely

where he became obsessed with mortality and filled with dread

and anxiety over his artistic legacy, he instinctively knew

he could no longer paint. On his death in 1944 Munch bequeathed

all of the art works in his possession to the City of Oslo,

which founded the Munch-Museet in

1963. Maybe this was a calculated and cynical move, by a dreary

Nordic bore, to defeat death by immortalising his art in a

morgue?

Alex Russell