|

Editor:

Marc Bridle

Webmaster: Len Mullenger

|

Seen and Heard Opera

Review

Britten, ‘Billy

Budd’: English National Opera, conductor Andrew Litton,

3.12.2005 (ME)

THE

‘INDOMITABLE’ ENO SAILS ON! Why the capitals, I hear you

ask? Well, I was just getting rather fed up with all those

headlines screaming things like ‘WHAT IS THE ENO FOR?’ and

all that easy copy about crises, being provided for the

latest semi-literate protégé of whichever ‘Arts Editor’

you care to name - of course, what some would really like

is for ENO to fold, thus allowing their beloved Royal Opera

to sail off into the sunset, trailing clouds of glory in

the shape of yet more subsidy and corporate jollifications.

Margaret Thatcher once ominously inquired ‘Why does London

need two opera houses?’ and that of course is the subtext

here: play up the ‘crisis’ at ENO and maybe – just maybe

– we’ll be able to get rid of all that plebby

stuff: well, hard luck – however much your researchers tell

you that ENO is in terminal decline, a show like this one

triumphantly asserts exactly what ENO is ‘for’

- a real company effort, the decks awash (sorry,

couldn’t resist that one) with mostly ‘home – grown’ singers

giving their all in a production of stunning theatricality,

with brilliantly committed playing from an orchestra which

sounds as if it would go to Hell and back for its superb

guest conductor.

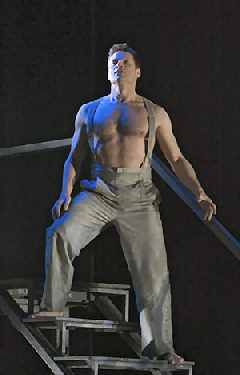

Simon

Keenlyside is a natural for the

role of Billy: Forster wrote of Melville’s creation that

he has ‘the goodness of the glowing aggressive sort which

cannot exist until it has evil to consume’ (Aspects of

the Novel) and Keenlyside

caught this perfectly: Britten’s presentation of him of

course reflects the composer’s preoccupation with innocence

destroyed by the hostility of its surroundings, and this

singer knows just how to convey that in every nuance. Superbly

graceful in his actions, his physical beauty (quite different

from the more ‘rugged’ Christopher Maltman,

who sang the part with WNO when this production was first

seen) renders his predicament all the more poignant, and

his singing left little to be desired: ‘Billy in the darbies’

pierced the soul, with the break in the tone at ‘But look:

Through the port comes the moon-shine astray’ and the understated

fervour of the final lament achieving the kind of stillness

and completeness which one so rarely hears. Keenlyside’s is a genuinely great performance, but not the only one, since the ENO

had wisely cast John Tomlinson as an exceptionally cruel

Claggart: in a letter to Britten, written in 1950, Forster

said ‘I want passion - love constricted, perverted, poisoned, but

nevertheless flowing down its agonising channel;

a sexual discharge gone evil. Not soggy depression or growling

remorse’ and this was exactly how Claggart is conceived

here: no pantomime villain, but as hidebound by the constriction

of his passion as a film character played by Eric von Stroheim

might be by his anger. ‘O beauty, o handsomeness’ was shattering,

Tomlinson’s crystalline diction allowing us to savour every

word, his tone so menacing yet so beguiling that we could

not avoid thoughts of Iago – ‘He

hath a daily beauty in his life / That makes me ugly.’

The

third member of the eternal triangle was less strongly characterized

by Timothy Robinson, who looks uncannily like Philip Langridge

on stage but who does not command the latter’s mastery of

Britten’s music. ‘Starry Vere’ is the most enigmatic character

of both novella and opera, and this ambiguity is always

a challenge to convey: Robinson was at his best in the opening

and closing scenes, taking us into his confidence with unaffected

skill, but at the more dramatic moments his voice was not

quite able to reach the expressive heights. Britten said

that it was ‘the quality of conflict in Vere’s mind’ which

had attracted him to the subject, and it falls to the Captain

to provide the most subtle reflections on the nature of

love, duty and law; Robinson may yet be able to evoke our

sympathies in this, but at present his characterization

is a work in progress. Melanie

Eskenazi Phoographs © English National Opera, Clive Barda

Back to the Top Back to the Index Page |

| ||

|

||||