|

Editor: Marc Bridle

Webmaster: Len Mullenger

|

Seen

and Heard Opera Review

Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods): Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of English National Opera, Colisuem, April 2, 2005 (MB)

Previously, I have been critically favourable towards the preceding three operas in Phyllida Lloyd’s, now-complete, Ring cycle for English National Opera. Twilight of the Gods, however, is the product of a sterile imagination, is dramatically weak and designed in such a threadbare fashion as to make the conclusion to Wagner’s cycle seem musically incomprehensible. The ENO orchestra, so wonderful throughout Siegfried, played sumptuously but by the beginning of Act III had succumbed to rabble-rousing through their very imprecise playing, something which one might calibrate to the sheer length and musical demands of the very long opening act (just over two hours in this production). Yet, beyond these criticisms one thing did save the day, and that was the singing; this was by some margin the most consistently inspired singing of the cycle, and in at least one instance reached world-class standards.

Act I opens with the prologue of the three Norms sat in their armchairs (evoking a similar image in Siegfried), their wisdom all embracing, the singing powerfully projected. Yet, when the curtain rose to find Brünnhilde and Siegfried sat at a table, entwined as lovers, one tended to consider less benignly some of the deficiencies of this cycle, which over-emphasizes the normality and ordinariness of the human condition to a sometimes crushing extent. Lloyd’s constant efforts to unite the drama of the Ring with parallels in film and documentary was reignited in Siegfried’s Rhine Journey, which allowed her to turn the Coliseum into a vast widescreen cinema. Against background images of forests, rivers and cities, Siegfried rode (or did he skateboard?) through time, a Wagnerian Indiana Jones (complete with hat), taking in glimpses of peepshows, advertising hoards, and clip joints. Its inspiration owed as much to Andy Warhol as it did to Michael Huhn, whose dark, pornographic, photo-reportage journey into the dark-side of sex it recalled all too vividly. The following scene between Siegfried, Hagen, Gunther and Gutrune took us into a clinically white world of medicine cabinets and beauty parlours, somewhat over-stating the image of Siegfried being given the potion which forces him into marriage with Gutrune. Only the scene between Waltraute (wonderfully sung by Sara Fulgoni) and Brünnhilde brought any sense of dramatic power to the act, and that was conveyed more through first-rate singing than it was any dramatic contextualization.

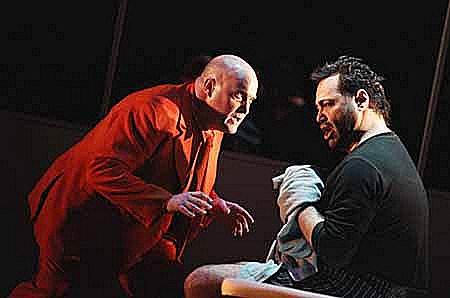

Act II, as so often in productions of this opera, is the core of the work and it brought out the best in both the design and the singers. Hagen’s dreamy illusions of his father, Alberich, was not just reflected in the sustained use of light, but also by the distortion of image in mirrors: Alberich walks menacingly behind glass, fingers tap on windows to wake Hagen from his dreaming, Gutrune is fondled erotically by a series of octopus-like hands crawling over her body. Perhaps the best-sung scene of the opera, Alberich’s urgings for his son to win back the ring for the Niebelungs conveyed tension and drama in every way. Andrew Shore’s Alberich is mesmerising (no wonder he is to sing the role at Bayreuth in 2006) but even he was overshadowed by Gidon Saks’ wondrous Hagen, moving between fear and child-like quivering in equal measure. The voice conjures up power in a quite extraordinary way, and everything he sings is done with complete fidelity to the text. Hagen comes to dominate the act, the voice tremulous with darkness and power, as he evokes his army of riot-police dressed followers to take arms (here seen as being cruise missiles ready for launching). It is the focal point of the production and it is magnificent. Perhaps the clumsiness of the scene changes reduced the impact of the following scene, but the joint weddings offered little in the way of insight or drama, and with Brünnhilde, like any jilted bride in her MFI designed bedroom, reduced to plotting revenge, the scene seemed inordinately dull.

It is, however, Act III which is the killer in this production. It is pretty much devoid of impact, drama or meaning, a series of beautiful images which, by themselves, cannot stand the test of the act’s duration. The opening lament from the Rhinemaidens – as they accompany and mimic the orchestral harps on their fringed curtains – is striking and evocative but, as in the opera’s final moments, it remains an image for the eye rather than giving any extended dramatic function. More than anything in this production – or indeed this cycle – it is Lloyd’s treatment of the death of Siegfried which left this reviewer bemused as to her intentions. Lacking any sense of pathos or tragedy, Siegfried’s death could simply have been a back alley knifing in any urban city centre, with only the image of his semi-crucifixion against one of the Rhinemaiden’s poles suggesting that Siegfried, despite his shortcomings, was a heroic figure. Sensationalized and trivialized, and done within the context of a near barren stage, the orchestra itself seemed to take part in this. There was none of the savagery so inherent in the music which Wagner wrote to accompany Siegfried’s death and funeral, and for the first time in the evening the orchestral playing seemed sparse and thin, etiolated to such an extent that it underplayed the importance of the scene to damaging effect. But worse was to come: returning to her (Phyllida Lloyd’s) constant image of the camera and flash photography, Siegfried’s body is stripped with the mourners and pole-bearers carrying off his hat, boots and clothes, the spoils of war, as he is unceremoniously photographed (the parallels with the paparazzi photographing the dying Princess of Wales uncomfortably suggested) and dumped on the ground in nothing but sacking. Brünnhilde’s final appearance conjures at least some hope that the end is near, but yet again Lloyd rips the drama out of this great final scene; it remains peculiarly stage-bound and the sense of anti-climax is palpable. As the Valkyries fasten a suicide bomber’s flak jacket to Brünnhilde’s body, the inevitability of what follows is soon enforced on us: Brünnhilde literally blows up Valhalla, and it is no more dramatic, or significant, than a grenade being exploded in a synagogue or railway station. Imagery returns to warm the eyes, but this is not the destruction of Valhalla that one remembers so vividly from productions by Chereau and Kupfer. The contorted figures that fall to the ground after Valhalla’s destruction seem evocative of Gericault’s Raft of Medusa, a not wholly inappropriate image given the analogy of water, but a not wholly convincing one either given that the destruction of Valhalla is a universal act of rebirth. Alberich’s final cry for the ring is all but obscured by the vast three-layered construction that depicts the Rhine being hauled up, it’s colour changing from flame red to azure blue, as the Rhinemaidens make their final appearance.

It is this very imaginative weakness, inherent throughout the opera, which makes this production of Twilight of the Gods such a struggle to watch. The clumsiness of the scene changes, the lack of inventiveness, and the confusion of ideas which seem momentarily juxtaposed but then contradictory, make it a very weak conclusion to the cycle. It would have been a catastrophe had it not been for the singers who somehow held in place deficiencies in the production values, weak and uneven choreography and the understated conducting.

As already suggested, Gidon Saks’ Hagen is the operatic star of the performance. He sings with blistering security from his bass-baritone voice, and yet is capable of the most mellifluous sounds as well as the most sheerly powerful ones. It is rare to find a voice of this calibre where the measure between his upper and lower registers is so evenly projected. He is due to sing the role at Seattle Opera and it should prove unmissable; and he may well become the Hagen of our time. Kathleen Broderick’s Brünnhilde comes a close second, her singing proving more mature and even than in previous parts of this cycle. The voice no longer seems under-powered for the vast ENO stage, and her final long monologue (translated in Jeremy Sams’ still demotic libretto as "Bring some timber, pile it up high") was magnificent from first note to last. That instability in the lower register had all but disappeared and the security of the voice at the top of the register was wonderfully firm. Unlike Saks, her enunciation remains a problem – very little of what she sang came across as comprehensible – but her assumption of the role of Brünnhilde is a triumph. Richard Berkeley-Steele’s Siegfried is still a force to be reckoned with vocally, and he exudes a youthfulness through both his sound and his acting that makes his Siegfried convincing. Iain Paterson’s Gunther has a luminous beauty to it, and a beguiling warmth, best exemplified in his final scene with Siegfried before both are killed. Claire Weston’s Gutrune is slightly insecure at the top of her register, but is beautifully acted. For once, the Rhinemaidens were an equal trio, with Linda Richardson, Stephanie Marshall and Ethna Robinson all enchanting.

Musically, Paul Daniel takes a troughs-and-peaks approach to this vast canvas. Act I frequently sagged, though Act II had the measure of the work’s power and darkness. Throughout both acts he obtained first rate playing from his orchestra; it was only in Act III that the orchestral playing slipped to unevenness of intonation and sonority (with some unwelcome and erratic horn playing), though the closing pages were wonderfully atmospheric and powerful.

The unevenness of this cycle – personified in this production – should perhaps surprise no one; Ring cycles aren’t usually of a sustained artistic quality throughout their long embryonic gestation. But, this Twilight is a profound disappointment, redeemed only by some outstanding vocal contributions.

Marc Bridle

ENGLISH NATIONAL OPERA WAGNER'S TWILIGHT OF THE GODS CONDUCTOR - PAUL DANIEL DIRECTOR - PHYLLIDA LLOYD DESIGNER - RICHARD HUDSON ALBERICH (ANDREW SHORE) HAGEN (GIDON SAKS) BRUNNHILDE (KATHLEEN BRODERICK) COPYRIGHT - NEIL LIBBERT

Back to the Top Back to the Index Page |

| ||

|

||||