|

Seen and

Heard Opera Review

Richard Wagner, Siegfried,

Soloists and Orchestra of English National Opera, Paul Daniel (cond),

Coliseum, 6th November 2004 (MB)

Siegfried throws up so many challenges –

orchestrally and vocally - that it is easy to distort its on stage

dramatic structure. Musically, this opera contains some of the starkest

and darkest music of the cycle (take, for example, the enormously

powerful prelude to Act III); any on stage action can seemingly detract

from the musical inspiration that defines it. This was precisely what

happened as the curtain went up on Act III – with an eruption

of applause that undermined the context of the scene between the Wanderer

and Erda. The blazing anger in both trumpets and trombones (and a

thrilling thunder machine) seemed somewhat underwhelming besides the

scene of Erda in a nursing home, surrounded by Norms sat in vast armchairs

knitting and drinking tea whilst watching on screen flames prematurely

engulfing Valhalla (a less than subtle attempt to capture our all

too human obsession, post 9/11, to watch disaster unfolding before

our eyes).

Similarly, one almost despaired at the forging song at the close of

Act I – accompanied as it is by music of breathtaking heaviness

in its brass chords – which showed Siegfried fashioning Nothung

with the minimal of physical effort. Rather than the labour of hammer

against anvil, the colossal effort required to finally forge the sword

and raise it aloft was accompanied by stage direction that created

the illusion of magic, with its static, flaring flashes of splintered

light, billows of steam and fiery-red background, which swamped Siegfried

as he pulled the sword from beneath the stage, symptomatic of production

values that seemed intent on diminishing the musical and over-egging

the dramatic into almost separate operatic entities.

These were disappointing moments, but so much else in this production

was outstandingly visualised, even if the singing remained uneven.

It was hardly surprising, given Phyllida Lloyd’s and Richard

Hudson’s domesticated Gods and mortals in Rhinegold

and The Valkyries, that Siegfried should open with

Mime’s hut viewed as an image of Faustian gloom. An old sofa,

cut out pictures pasted onto the walls, a bunk bed, a dirty sink (and

enough food to feed an army) made the Mime/Siegfried relationship

seem spellbindingly normal. When Siegfried entered (bear in tow) it

was as if a young, teenage skater had accidentally popped up on stage:

with his baseball cap and baggy jeans, Richard Berkeley-Steele made

a decent stab at knocking 20 years off his age, and this only got

more convincing as he toyed around with battery operated jeeps, listened

to music on a Walkman and read magazines in bed. This may well be

the most ‘teenage’ Siegfried I have seen on stage. Yet,

Berkeley-Steele, if not always resplendent of tone, had a youthfulness

to his voice that matched his impetuosity on stage, a more than decent

contrast to John Graham-Hall’s Mime, acted not only with slippery

craftsmanship, but sung with characterful precision throughout. Here

at least both singers moved with the orchestration: Siegfried quietly

lyrical, Mime psychologically dark and sombre (and in his final Act

II scene bordering on the demented). As in Valkyrie, Robert

Hayward’s Wanderer had vocal authority and a hefty tone, even

if one missed some warmth to his phrasing (but do we really feel this

singer’s presence when Wagner alludes to him through the majesty

of his orchestration?)

Gerard O’Connor’s tattooed Fafner remains an imposing

creation and is splendidly sung. If the dragon-like breathiness of

the orchestral prelude to Act II didn’t quite prepare us for

subsequent amplification of his voice, it was overshadowed by Lloyd’s

and Hudson’s skilful use of lighting to convey his physical

presence. Emerging from his bath (a recurring image in this cycle,

just as fire extinguishers are) – and growing ever taller as

he did so – his pre-destined death at the hands of Siegfried

nevertheless seemed to have an echo of menace about it. And here we

got the first coup of this production: stumbling on stage, bloodied

and covered in plastic sheeting, Fafner was all but eclipsed by Berkeley-Steel’s

majestically introspective Siegfried: vocally impressive, we get the

first hints of Siegfried as hero (as opposed to anti-hero) as power

finally seems to make us to warm to him. It’s a short-lived

moment, however, because the appearance of the Woodbird (a rather

squally Sarah Tynan) on a scooter throws us back to the image of the

hip-skater Siegfried, something that robs what has preceded it of

any long-term significance. Tynan’s voice improved markedly

during the opening of Act III (only to be overshadowed by the richly

toned Erda of Patricia Bardon) but a kind of Keystone-cop type farce

bloodied events as Siegfried petulantly overturned chairs, throwing

the Norms and Erda to the ground in the process. Suddenly, the anti-hero

was before us again.

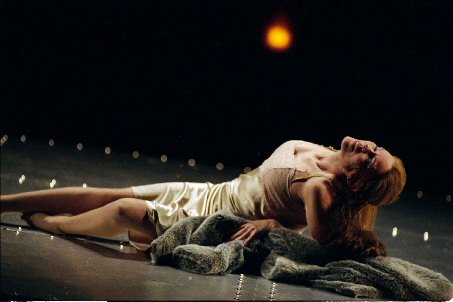

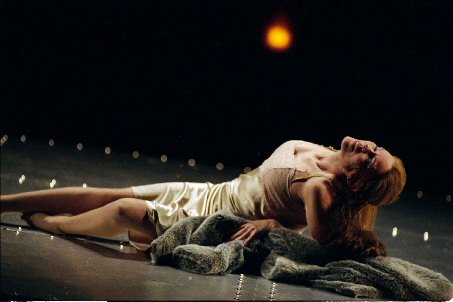

But the depth of Berkeley-Steele’s characterisation of Siegfried

is that he is always greater than the sum of his parts. Thus, when

he happens upon Brünnhilde (Kathleen Broderick) after breaking

through the curtain of fire he is seemingly heroic, physically towering

and simply unaware of fear as he seeks to wake her from sleep. If

his ascent to the summit is perhaps more an ascent from below, in

a moment of startling beauty, we see the shadow of Brünnhilde

cocooned like an Egyptian mummy; Siegfried’s prize to her as

they embrace is for her to throw off the shackles of her imprisonment

and make her blossom like a newly born butterfly. Here the orchestra

under Daniel excelled themselves: radiant, high violins were as pure

of tone as you could have wished for, rekindled like oxygen breathing

life into fire, replacing the almost endless subterranean orchestration

that preceded it. That it should actually have been noticed at all

is to Daniel’s and the orchestra’s credit. The radiance

that develops after this moment was taken by both Broderick and Berkeley-Steele

to ignite vocal as well as physical passion. It was a perfect summation

of their fusion of ecstatic, lyrical affirmation, and a fitting conclusion

to this production.

Siegfried showed Lloyd and Hudson more confident in their

vision of this ongoing cycle, and that confidence is replicated in

the orchestra pit as well. The ENO orchestra – especially the

brass – were both magnificent and resplendent and Paul Daniel

showed less unevenness in his grasp over the score than he has done

in earlier parts of this Ring. Indeed, this production is almost a

triumph.

Marc Bridle

Picture credits: John Graham-Hall

(Mime), Richard Berkeley-Steele (Siegfried), Robert Hayward (Wanderer),

Kathleen Broderick (Brünnhilde) – photographer, Neil Libbert.

Further Listening:

Richard Wagner, Siegfried, Soloists, Bayreuth Festival Orchestra,

Herbert von Karajan, MYTO HO55

Back to the Top

Back

to the Index Page

|