|

Seen and Heard

International Opera Review

Gyorgy Ligeti,

Le Grand Macabre, San Francisco Opera, Alexander Rumpf

(conductor), War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, November 18,

2004 (HS)

What a strange and exhilarating ride this is, this absurdist opera

with music from the pen of one of the 20th century's most distinctive

and iconoclastic composers. It opens with a toccata for 24 car horns

that nods to Monteverdi's Orfeo, the Latin Dies Irae

and a Bach chorale while somehow devolving inevitably into something

evocative of geese laughing. It ends with a passacaglia that, to my

ears, seems to strive toward Palestrina's polyphony as if filtered

through an acid trip. And if that isn't weird enough, along the way

there are coy references to Beethoven's Eroica symphony,

Stravinsky's Histoire du Soldat and Ligeti's own Requiem

(the weaving voices used by Stanley Kubrick in the film "2001:

A Space Odyssey").

On second thought, strike that. These elements are buried in Ligeti's

own musical palette do seep as to be noticeable only if you're looking

for them. Ligeti is quoted in the program book as saying he tried

to bury them as if grinding some dropped food into the carpet, an

apt metaphor for the opera's message - that humanity's gritty sense

of humor can triumph even over death. That sense of élan can

be scatalogical and lewd; it's not for nothing the opera is set in

a mythical place called Breughelland, named after the Flemish painter

of wildly playful scenes. But it has the advantage of leavening the

story of Death coming to wipe out humanity. He bungles the deed when

his chosen human cohorts get him drunk at just the right time.

San Francisco Opera's performances represent the U.S. debut of this

opera, which was first performed in 1978 in Stockholm and has had

some three-dozen revivals in Europe, including a revision in 1997

in Salzburg. This production, borrowed from Royal Danish Opera Copenhagen,

uses the Salzburg score. Designer Steffen Aarfing and director Kasper

Bech Holten (both of whom worked on the production debut in 2001)

use comic-book primary colors and several theatrical devices provide

some framework to the bizarre goings-on. In each scene, a thought

bubble drops down from the flies to suggest what a character might

be thinking in response to what's just happened, and at some point

a frame drops down to highlight one aspect. These devices just emphasize

the cartoonish aspect of the story.

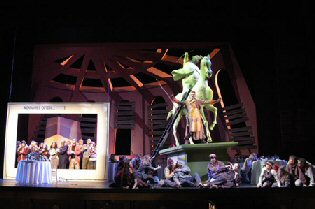

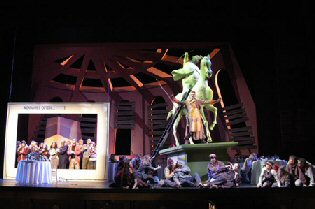

The curtain goes up on a post-apocalyptic scene of fallen buildings.

Ill-clothed, ill-fed rabble populate the stage. A frame drops down

to show the shop of Piet the Pot (tenor Graham Clark), a self-described

"wine taster" who goes well beyond tasting. He sings an

aria in praise of wine, punctuated with burps. A pair of lovers (mezzo

Sara Fulgoni as Amando and lyric soprano Ann-Sophie Duprels as Amanda),

oblivious to the rubble, sing soaring Straussian lines. They eventually

retreat to a tomb to copulate endlessly.

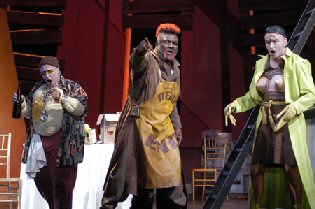

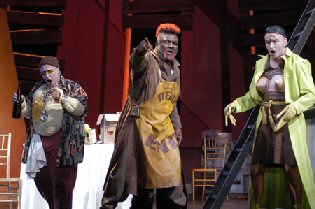

Out of the tomb emerges the title character, Nekrotzar (bass baritone

Willard White), to announce the end of the world by midnight. With

garish red and yellow hair shaped into a Mohawk and a strangely shaven

goatee in the same colors, wearing pearl-red sunglasses and elbow-length

work gloves, a filthy yellow apron inscribed with the words "Dead"

and "End" adding its own touch, White seemed to be channeling

the flamboyant actor and ex-basketball player Dennis Rodman. As sonorously

as he sang his dead-serious music - and White's voice was glorious

- the get-up made the character impossible to take seriously.

Piet the Pot, driven to blathering (the thought bubble drops down

to show Nekrotzar thinking, "Is he nuts?"), falls under

the newcomer's spell, but hardly anyone else does, at least not for

long. The rest of the cast is far too interested in their own affairs.

In the second scene, Astradamors (bass Clive Bayley), the royal astrologer,

wearing a conical bra à la Madonna, is surrendering to his

housekeeper, Mescalina (mezzo Susanne Resmark in a wonderfully brassy

turn), in a parody of a sado-masochistic scene. Frame drop: "Mescalina's

Dream," in which she asks a lovely Venus (coloratura soprano

Caroline Stein) for a real man. Nekrotzar arrives to give Mescalina

the rogering she can't get from the wimpy astrologer. Relieved to

be out from under Mescalina's whip, he joins up with Nekrotzar as

he goes off to spread the word of humanity's demise.

Scene three shifts to the palace, where two politicians (tenor John

Duykers and bass Joshua Bloom), one clad in white the other in black,

spout epithets at each other while they maneuver to keep the Prince

(counter tenor Gerald Thompson) in his own palace separated from his

people, who are milling outside. There are some arch references to

the recent presidential election. Gepopo, the head of the secret police

(Stein), enters furtively in black tights and a red military top,

cell phones strapped to her hands, singing lavish coloratura to say

that a comet is heading toward earth to end the world. Nekrotzar bursts

in, followed by the crowd. A wandering violinist plays something like

the bastard child of the Devil's music from Histoire and

ragtime. Piet and Astradamors are sidetracked by the prince's foods

and wines, and, eventually, so is the angel of death.

In scene four, everyone gradually realizes that they are still alive,

the lovers are still singing soaring music, and Nekrotzar enters,

looks around and mutters, "shit." The inhabitants of Breughelland

have survived for another day. Love triumphs. So do lust and other

appetites.

The glue that holds this unwieldy grabbag together is Ligeti's music,

which is worth hearing all by itself. It's a riot of ideas, splattered

across a vast canvas yet ultimately pulled together into a masterful

arch. The individual moments are sharply etched, and the cumulative

effect is like being pulled along by a barely in-control team of horses

as the scenery flashes by. Michael Boder, who was to conduct the entire

run, got only through the first performance Oct. 29 when he suffered

a back injury that required surgery. Alexander Rumpf, music director

of the Oldenburg (Germany) State Theater, stepped in for the rest

of the run. He led a lively performance Nov. 18.

Pamela Rosenberg, whose tenure as San Francisco Opera general director

ends after next season, has taken a lot of heat from patrons and some

writers (including this one) for indulging too often in Eurotrash

productions and bringing in far too many unknown European singers

whose voices disappear in the vast interior of the 3,200-seat War

Memorial Opera House. If ever a production high in Eurotrash was meant

to be, however, this is it - precisely because it mocks the style.

The cast was strong from top to bottom. I wouldn't mind hearing Stein

have a go at Violetta (or even the Queen of the Night) and Graham

Clark can sing any character tenor role he wants to, as far as I am

concerned.

As such, Le Grand Macabre joins 2002's astoundingly

powerful Saint François d'Assise - reviewed

here - (which also starred Willard White) as high water marks

for Rosenberg's time here. It took guts to stage these strange operas,

both of which represented long-delayed U.S. debuts. Audience response

was more enthusiastic for Saint François, but this wasn't bad

at all. There were empty seats around the edges for this performance,

but those were there responded with big grins and loud applause.

Harvey Steiman

Pictures © San Francisco Opera

Back to the Top

Back

to the Index Page

|