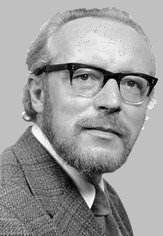

Kenneth Leighton

(1929-88)

With the death of Kenneth Leighton in

1988 the world lost a composer of great

distinction. Born in Wakefield on October

2 1929, he was a chorister at Wakefield

Cathedral and was educated at the Queen

Elizabeth Grammar School. While still

at school he gained the LRAM Piano Performers

diploma.

In 1947 he went up

to The Queen's College, Oxford on a

Hastings Scholarship in Classics: in

1951 he graduated both BA in Classics

and BMus, having studied with Bernard

Rose. In the same year he won the Mendelssohn

Scholarship and went to Rome to study

with Petrassi.

Kenneth Leighton was

Professor of Theory at the Royal Marine

School of Music 1951-53 and Gregory

Fellow in Music at the University of

Leeds 1953-55. In 1956 he was appointed

Lecturer in Music at the University

of Edinburgh where he was made Senior

Lecturer and then Reader. In 1968 he

returned to Oxford as University Lecturer

in Music and Fellow of Worcester College.

In October 1970 he was appointed Reid

Professor of Music at the University

of Edinburgh, the post which he held

until his death in 1988.

Among the many prizes

for composition awarded to him were

the Busoni Prize (1956), the National

Federation of Music Societies Prize

for the best choral work of the year

(1960), the City of Trieste First Prize

for a new symphonic work (1965), the

Bernard Sprengel Prize for chamber music

(1966) and the Cobbett Medal for distinguished

service to chamber music (1967).

In 1970 the University

of Oxford awarded him the Doctorate

of Music, and in 1977 he was made an

Honorary Doctor of the University of

St. Andrews. He was elected a Fellow

of the Royal College of Music in 1982.

As a pianist Kenneth

Leighton was a frequent recitalist and

broadcaster, both as soloist and in

chamber music. His music is widely performed

and in increasingly available on CD.

Mrs J.A. Leighton,

38 McLaren Road,

EDINBURGH,

EH9 2BN,

Scotland

UK

Tel: 0131 667 3113

Email: Jo

Leighton

The

Leighton Trust (with link to concert

information)

Leighton

Discography

Kenneth Leighton - a 75th Anniversary

Tribute

by Paul Spicer

What makes a composer worthy of the

attention of posterity? Why does part

of this tribute regret the far-too-widespread

neglect of such a composer as Leighton?

To my mind, a composer should have the

technique to put his ideas across eloquently,

have the ideas worthy of that technique,

and an inner creative fire which communicates

those ideas powerfully. The commentator

Hugh Ottaway once said most tellingly,

'idioms come and go and history finds

little to choose between them; the enduring

factor is the quality of thought, which

alone makes the idiom a living and vital

thing'. At one stroke he demolishes

the whole fashion bandwagon and puts

the emphasis squarely where it belongs

on the composer's creative integrity.

Leighton always had a very strong Romantic

streak. His earliest works such as the

beautiful Veris Gratia for oboe, cello

and strings show his indebtedness to

Vaughan Williams. It is no surprise

that Gerald Finzi at the end of his

life championed his music, encouraging

this shy, working class northern lad,

giving him his first performances with

the Newbury String Players and thus

gaining Leighton's eternal gratitude.

Wakefield Cathedral was the first point

of musical inspiration, and here it

was that Leighton discovered the great

panoply of music for the church which

he himself so greatly enriched in future

years. Careful nurturing at Oxford by

Bernard Rose in particular ensured that

his extraordinary natural compositional

talent should be developed and recognised.

First success came in the form of a

Mendelssohn scholarship to study with

Petrassi in Rome in 1951-2. This experience

gave him wings and allowed his natural

lyricism to flow between the science

of contemporary techniques (which he

used but rarely allowed to dictate style)

and the ebb and flow of timeless counterpoint

of which he was a master.

Leighton's stated influences were many

and varied and included Bach and Brahms.

If his developing style seemed far removed

from the sound world of these mentors,

essential elements of their style and

processes became his staple diet. One

of the most significant statements of

Leighton's process came when he said

'All my days are spent trying to find

a good tune'. If this is an exaggeration,

it underlines the most important quality

of his music which he shares with Bach

and Brahms, that of lyricism. He also

gained another hugely powerful tool

from them in his use of pathos. Brahms

understood the power of pathos instinctively.

One only has to look at the simplicity

of that perfect piano Intermezzo op.117

no.1 or the Amen from the Geistliches

Lied op.30 to know how deeply he understood

the power of quiet, reflective simplicity

to affect the senses. Leighton, too,

understood this and the third of the

Romantic Pieces for piano op.95 is a

moving example. This piece, for me,

sums up why I believe Leighton deserves

that recognition from posterity which

I questioned earlier. It is only one

example of which there are many, but

it demonstrates timeless qualities which

I believe to be essential to the positive

judgement of future generations including

a deep sense of humanity, of quiet protest,

of overriding sensitivity, of joy and

sadness, of resignation, and in the

end quiet acceptance of the inevitable.

It is a life's journey in microcosm.

Leighton talked of 'wonder' in nature

when referring to his solo cantata Earth,

Sweet Earth op.94. And if one characteristic

seems to communicate above all others

in his music it is this searching for

something other - for meaning in life

and the order of the universe, God and

Love which brings an added dimension

to his creative genius. Perhaps, if

I were to pare it down to its basic

elements I would recognise the quality

of ecstatic spirituality which is seen

in both his life-enhancing scherzi as

well as his reflective meditations.

Possibly Leighton's strongest card,

however, is that all this emotional

content is so finely balanced with the

acuteness of his intellect and his ability

as a pianist. Each of these elements

fed the others. Thus, there was always

the practitioner's practical appraisal

of what was possible in performance

and the intellectual's appraisal of

the challenge of balancing the elements

of heart and mind, style and content.

Nowhere is this more clearly demonstrated

than in the Fantasia Contrappuntistica

op.24 - a homage to Bach which won the

Busoni Prize and was premiered by Maurizio

Pollini in 1956.

Perhaps Leighton's misfortune was to

be born at a time when musical experimentation

was at its height. Thus, his rather

conservative style made even his serial

compositions a search for lyrical possibilities.

He was also to some extent a formulaic

composer whose mannerisms were often

transposed from work to work and detractors

would find reliance on certain notational

figures and rhythmic cells tiresome.

But this very insistence on his developed

style was part of what makes the unique

experience of Leighton's music. Hugh

Ottaway's assertion about idiom goes

to the heart of the matter. Sixteen

years after his untimely death we are

in a better position to recognise Leighton's

vibrant creativity, his deep sensitivity,

his communicating spirituality and the

depth of his intellectual and technical

prowess. We now need performers in all

genres to take this music to their hearts

and to allow it to work its magic on

a new generation of audiences.

© Paul Spicer

This article appeared

in The Full Score - a publication issued

by the MusicSales Group 2004