Fabric of Britain – The Story of Wallpaper on BBC4.

Presenter Paul Martin. September 2013. Have you ever entered a room and stopped the conversation? Well it

seems that I have discovered the perfect conversation stopper. At a

BBQ a group were discussing what they had been watching on TV so I asked

if anyone had watched the programme on the History of Wallpaper. This

was greeted with open-mouthed astonishment followed by embarrassed tittering.

Nevertheless the loss was theirs as the programme itself was extremely

interesting so below I present a summary in case you missed it. The story of wallpaper in Britain goes back to the Sixteenth century.

Sheets of printed paper were being sold by stationers for lining boxes

and drawers. People started hanging these on the walls. If they trimmed

the sides of the paper they were able to match the patterns. Samples

of such paper have been found in Temple Newsam House, Leeds dating from

1670. This became so popular that special papers for walls were printed

and were known as paper hangings and aped silk damasks, tapestries and

embroidery used by the aristocracy. The papers literally did hang in

the same way that fabrics were hung. They were tacked up top and bottom

and down the sides but not glued. The edge of one paper was cut and

used to overlap the unprinted side of the next sheet. Hangings of this

type from the 1670s can be seen at Ham House near Richmond Surrey. The

tacks were hidden by paper borders. These borders soon became decorative

features in their own right. I have not found out how the borders were

mounted but if their role was to hide the tacks they must have been

glued rather than tacked. Gill Saunders references the use of glue in

1734 ( a paste of best flour and water) Papers continued to have overlapped sides right up to 1914 when it

was superseded by the butt joint we use today. Heavier papers required

a stronger paste which was achieved by adding gelatine, gum arabic or

animal glue. For heavy flocks a pure scotch glue was made from animal

hoof and horn, this has the advantage that the papers are more easily

removed from the wall later.. When papers were glued directly onto the

wall damp was often a problem causing discolouration so the lining paper

was introduced. James Arrowsmith in the Paper Hanger's and Upholsters

Guide (1840) recommends the use of battens and canvas as a protection

against damp. This also made the papers portable. It was commonplace

to paste new papers on top of old papers. This help to smooth out any

irregularities in the walls but is also why we can sometimes see evidence

of the early papers in old houses – as many as 22 layers have been found.

Not all wallpapers were cheap. Upmarket papers were made of flock,

imitating silk velvet. Eighteenth century British flock wallpapers became

the envy of the world and were even exported to France who traditionally

exported their papers to us. Originally papers were prepared in individual

sheets but then sheets were linked by folding and compressing the ends

with animal glue to create much longer sheets that could be wound on

a roll for printing by machine. The standard width was 21 inches. Only

later were continuous rolls manufactured. To make a flock the background

colour was applied to the paper. Four coats of colour were applied followed

by a gloss coat to give a sheen. The pattern was then applied by wooden

engraved blocks with the pattern in relief. When papers were originally

made in sheets the pattern had to be quite short but, with the invention

of the roll, patterns could be much longer – in fact as long as needed.

The flock pattern wooden block was coated in a slow drying paint or

glue which was applied to the paper and the flock sticks to that. Originally

flock was hand-cut wool which was fairly long and led to an uneven finish.

Eventually flock was prepared by grinding wool which gave a much finer

flock. An interesting point which was not touched upon in the programme is

that there was a wallpaper tax in this country. It was introduced in

1712 at a rate of one penny per square yard but this rose in stages

to one shilling a square yard and effectively stopped the production

of British wallpaper. The tax was abolished in 1836 for British papers

but imported papers were taxed for a further 25 years. There are two records of papers used at Charlecote: Chris Purvis has given me the following information he found in the

Warwick records Office Sir, I have sent off Mr Waggen (directed to you at Stratford

on Avon) the following quantities of paper, which I believe you will find according to your order.

28 pieces of 12 yds 336 yds Crimson for three rooms

25 do do 300 yds Green & Metal for large bedroom

& two .... rooms 17 do do 204 yds Satin for yellow room and turret

I suppose your paper hanger is accustomed to the

hanging of Flock and Metal paper, which require very great care, and

they should have very smooth and stout lining paper under them; and

the joints well rubbed down before the printed paper is applied. I trust

that if well …. These papers were used in the South Wing and would have

been subject to the Wallpaper tax Ted Veitch says the Charlecote Dining room flock paper was designed

by Willement and matches the carpet. It came as 23 hand-printed pieces

in 1837 and cost £71 17s 6d which included the hanging. The paper-hangers

came up from London with the paper. This paper avoided the Wallpaper

tax. The strips were made to measure and then put on a roll for easier

transport but were not printed as a roll. A backing paper was used and

the the glue was horn and hoof. Ted thinks the flock was stuck on with

this glue and it is the protein content that has attracted the fungal

growth we see as black spots on the paper. There is no easy cure for

this although the paper is vacuumed every year to remove fungal spores

that might otherwise be breathed in. A way of avoiding the wallpaper tax was to put up plain papers and

then colour by hand. These were usually coloured green or blue and were

known as verditer papers. These papers could also be flocked on the

wall. In the late seventeenth century Chinese hand painted papers were imported.

These were an expensive luxury and were treasured because of the detailed

scenes By the end of the eighteenth century every Grand House had at

least one Chinese room. The papers were specifically made for the British

market and not used by the Chinese themselves. British manufacturers

were quick to follow with their own printed designs of Chinoiserie.

There was an evergrowing range of patterns, florals, geometric patterns,

stripes, patterns that looked like architecture or like pictures hung

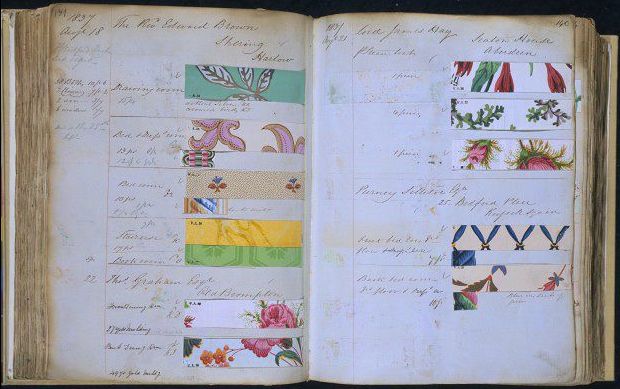

on a wall. We can tell what patterns people were choosing as there exists

an order book from Cowtan & Sons covering 1824 to 1830 that has

strip samples from the actual paper glued into the book. Cowtan Order book 1836-1842 Victoria and Albert Museum Even as late as 1830 paper was still being printed in blocks with

the sheets glued together as described but then machines appeared that

could manufacture continuous paper rolls with a steam powered machine

being patented in 1839. By 1870 a number of different colours or patterns

could be sequentially applied to the moving paper. This was done by

applying colours to blankets on rollers which transferred the paint

to embossed blocks which in turn applied the paint to the paper as it

passed. They could produce 250 rolls an hour. By 1834 just over a million

rolls of wall paper had been printed by hand. 10 years after mechanisation

Britain produced 5.5 million rolls, in 1874 32 million rolls were made.

Hand made paper sold at 25 shillings a roll but mechanisation brought

this down to 2 pence a roll.

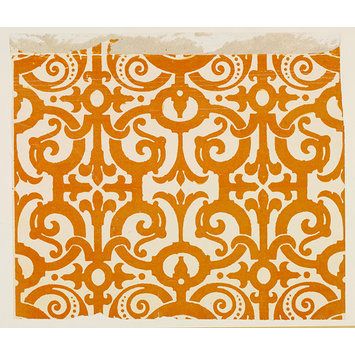

The V&A description is Portion of wallpaper with a strap-work design;

Woodblock print on paper This same pattern appears in green in a Cowtan order book in 1837 so

it was generally on sale. Cowtan were in Oxford Street, London. On Sunday 6 October 2013 I was guide in the Billiard Room. I was chatting

to a lady about the wallpapers in the house when she said her friend

was a wallpaper expert; naturally I asked to speak to her friend! It

turned out she was Liz Cooper and employed at Oxburgh Hall, a National

Trust house; either she was in charge or was the house steward, I forget!

She was a wallpaper expert. I said we understood the Billiard Room wallpaper

to be a fairly standard type bought commercially in about 1956. She

prefaced her remarks by saying she would not put her professional reputation

on the line on the basis of a brief look but said no it was not what

we thought. She ran her fingers over the paper (naughty naughty!) and

said she felt it was a hand-blocked paper and more likely to be of 1856

than 1956. She was quite excited by the border and said it was definitely

hand blocked and quite elaborate. Stewart Scott

|

The

Dining room paper dates from 1837 and is a floral arabesque on an embossed

gold paper. THis V&A sample is bright and clean and does not have the

mould growth from which the paper in the house suffers. Willement also

used this design in the Axminster carpet made by Wilton. It is a red,

blue and buff design on a russet ground. The date of manufacture is

uncertain. The V&A dates it between 1828 and 1844 but it was likely

made at the same time as the wallpaper.

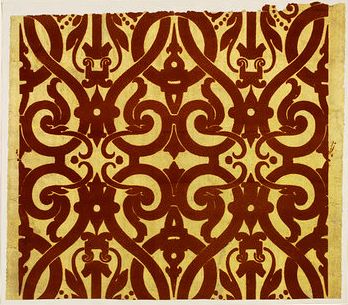

The

Dining room paper dates from 1837 and is a floral arabesque on an embossed

gold paper. THis V&A sample is bright and clean and does not have the

mould growth from which the paper in the house suffers. Willement also

used this design in the Axminster carpet made by Wilton. It is a red,

blue and buff design on a russet ground. The date of manufacture is

uncertain. The V&A dates it between 1828 and 1844 but it was likely

made at the same time as the wallpaper. The Library wallpaper is a flock strap-work design on an embossed gold

ground designed by Willement in 1837. The design was inspired by the

girl's dresses in the painting in the great Hall (see below). It also

appears on the cushions of a suite of library chairs later covered by

the National Trust in a glazed Chintz replica shortly after the house

was acquired. I do not know which came first; the wallpaper or the cushions.

The Library wallpaper is a flock strap-work design on an embossed gold

ground designed by Willement in 1837. The design was inspired by the

girl's dresses in the painting in the great Hall (see below). It also

appears on the cushions of a suite of library chairs later covered by

the National Trust in a glazed Chintz replica shortly after the house

was acquired. I do not know which came first; the wallpaper or the cushions.