From the Library The Naming of Plants - three early botanists The Charlecote library holds a copy of: see also TV Programme Timothy Walker: A Blooming History Having published the first edition he came to London to present it

to the Royal Society. There was uproar because of the way he presented

his work. He wanted to meet Phillip Miller whose ambition was to introduce

a clear simple and universal way of naming plants. Plants were given

all sorts of names and from their descriptions it was not possible to

be sure that two descriptions applied to the same plant. This made research

very difficult. So Miller founded the Society of Gardeners which met

monthly in Chelsea and compared new plants coming in from all over the

world with established examples. Eventually the Society buckled under the sheer volume of plants but the work made Miller's name and he was appointed Head of the Chelsea Physic Garden which still exists today. Miller was there for 50 years with the garden representing not just medicinal plants but also plants of economic importance such as dye plants (e.g. Woad) and fibre plants such as sisal used in rope making and cotton which eventually made America!

Crassula (Perfoliata) follis lanceolato-funbulatis feffilibus connatis canaliculatis fubulus convexis -Tallest Crassula with perfoliate leaves (having a leaf base that completely encloses the stem, so that the stem appears to pass through it - my explanation not from Miller).

The entry in the Full Gardener's Dictionary (volume 1) (not in the Charlecote library) is more helpful.

He goes on to say The reason for this was, that the plants had not then produced flowers in Europe, so they had to be classed by the outer face of the plants. These plants are natives of the Cape of Good Hope. from whence they were brought into the European gardens. The first sort (Crassulat altissima perfoliata) does not send forth any side branches, unless the top be cut off, but it may be trained up to six or eight feet high.

Linnaeus wanted to meet Miller to try to persuade him to include his sexual methods of classifying plants in his dictionary. Miller refused and Linnaeus described Miller's work as mere plant collecting. Linnaeus met a German botanist studying in London, Johann Jacob Dillen Dillenius, Dillenius had read Linnaeus' book but found it unconvincing but did admire his knowledge of plants and the two became life-long friends.

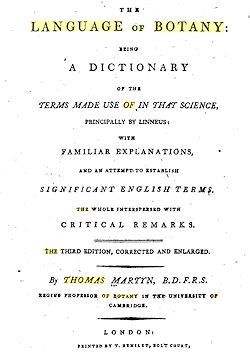

Linnaeus returned to Sweden and established the National Botanic Garden at Upsalla and laid it out according to his sexual system - as it still is to this day. In Sweden he had status and money and eventually was knighted in 1757 when he took the name Carl von Linné. Plants were given very long names that described every aspect of the plant. Linnaeus recognized that this was unworkable but realised a plant name did not actually need to describe a plant but just be unique. He had also realised that plants could be grouped into Orders, Genera and species. His greatest contribution was the adoption of just two names for a plant (the latinized binomial) the first being the Genus and the second the specific epithet. For instance the tumbleweed known variously as Jim Hill mustard, Tall mustard, Tumble mustard, tumbleweed mustard, tall sisymbrium, and tall hedge mustard is now identified as Sisymbrium altissimum. In his Spcies Plantarum 1755 he named over 7000 plants. The binomial nomenclature was accepted all over the world except by Miller who only finally included it in his final 8th edition 1768. Also in the Charlecote library is a copy of The language of botany . being a dictionary of the terms made use of in that science, principally by Linnaeus: ... By Thomas Martyn.(1793) Thomas Martyn was Regius Professor of Botany at Cambridge University and an early adopter of Linnaean classification and nomenclature, which he promulgated in his public lectures. In this work, based on a paper given to the Linnean Society in 1789, he defines hundreds of Linnaean terms. This book may be read on-line. The URL has 117 characters so for those reading a paper copy of this article I have created a shorter URL: http://tinyurl.com/mfsz7tb

Len Mullenger is a Sunday volunteer guide. Any comments are welcome and can be sent to len@musicweb-international.com All articles can be read at http://www.musicweb-international.com/Charlecote

Return to Index page

|

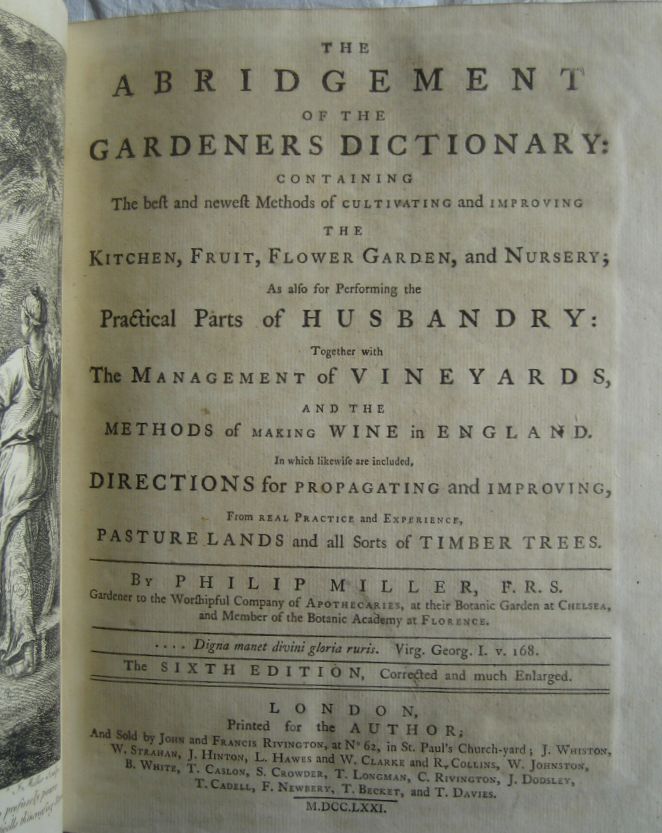

Miller took all the notes from the Society of Gardeners and put them

in his Gardener's Dictionary which went through eight editions. We hold

the 7th edition of the abridged version (1771). This really is a list

of names and is a very dry read. However he has started to indicate

the latinized binomial as you can see for the entry:

Miller took all the notes from the Society of Gardeners and put them

in his Gardener's Dictionary which went through eight editions. We hold

the 7th edition of the abridged version (1771). This really is a list

of names and is a very dry read. However he has started to indicate

the latinized binomial as you can see for the entry: Crassula

altissima perfoliiata Tallest Crassula with leaves surrounding the

stalks. Commonly called Aloe perfoliata

Crassula

altissima perfoliiata Tallest Crassula with leaves surrounding the

stalks. Commonly called Aloe perfoliata